Some Opioid Addictions Begin in the Hospital

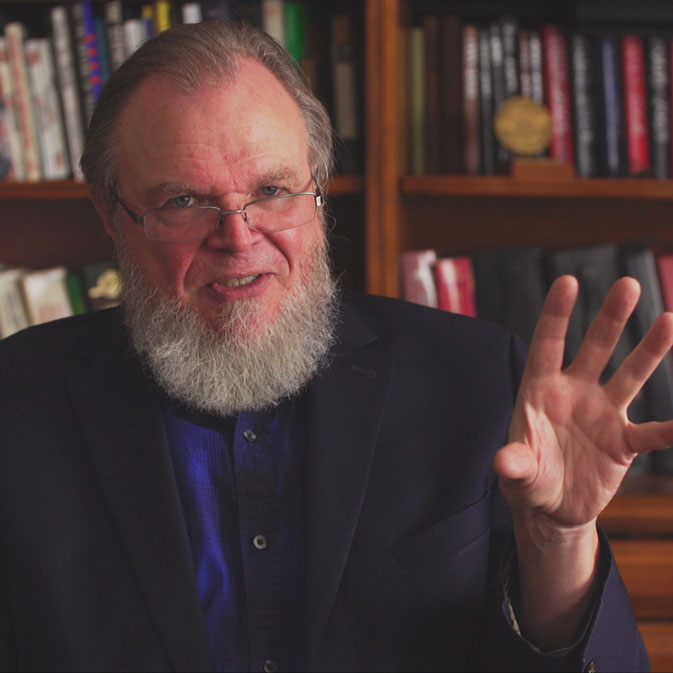

In a recent podcast, “A first-hand account of kicking Fentanyl addiction: reversing Hebb’s law” (May 12, 2022), Walter Bradley Center director Robert J. Marks interviews a man who got addicted to Fentanyl as a medical drug.

“Stretch” tells us how he got hooked and how he finally beat the narcotic, without once going to the street for help, though his experience was challenging, to say the least. Readers may also wish to read or hear anesthesiologist Richard Hurley’s perspective here and here.

Before we get started: Robert J. Marks, a Distinguished Professor of Computer and Electrical Engineering, Engineering at Baylor University, has a new book, coming out Non-Computable You (June, 2022), on the need for realism in another area as well — the capabilities of artificial intelligence. Stay tuned.

This portion begins at approximately 01:00 min. A partial transcript and notes, Show Notes, and Additional Resources follow.

Robert J. Marks: Donald Hebb (1904–1985) is considered the father of neuropsychology because he first effectively merged the psychological world and the world of neuroscience. He is known for Hebb’s Law. We study it in artificial intelligence — and it’s part of brain chemistry.

Hebb’s Law says that, neurons that fire together, wire together. In terms of addiction … the path between the neurons dedicated to the action and the neurons dedicated to the pleasure build up in strength. So the path becomes stronger and stronger. Triggers eventually push you towards performing the action to experience the pleasure…

Our guest today was addicted to opioids, specifically the highly potent synthetic opioid, Fentanyl. And we’re not going to disclose his identity; we’ll simply call him Stretch.

Well, first of all, Stretch, et’s get legality out of the way. You never purchased fentanyl off the street. I think all of the drugs that you became addicted to were prescribed by physicians. Is this right?

Stretch: Yep.

Robert J. Marks: And I do know that you suffered from a series of failed surgeries. Let’s talk about these. Could you kind of go through the surgeries and the pain associated with each one, and then the corresponding opioid prescriptions you were given?

The serious digestive system problem that started Stretch on the road to opioid addiction

Stretch: I got diagnosed with inflammatory bowel disease; this was 1999. It was after a long period of bleeding, basically bloody diarrhea continuously. And urgent. Urgent. But it was always lots of blood.

Before I ended up at the gastroenterologist, my general practitioner kept diagnosing me with hemorrhoids. In reality, the failings of the medical community started with the late diagnosis of this disease … before my general practitioner walked through the insurance-approved steps to get me a proper diagnosis. And initially, the inflammation was seen with a barium enema, which is a horrible experience. You don’t want to be in front of a doctor who is standing behind a sheet of Plexiglas to assess you. That’s never a good situation.

Robert J. Marks: Wait, wait, there was a Plexiglas between you and the doctor?

Stretch: Yes, because I had received a barium enema for the imaging. And when he came in, he wanted to protect himself in case the barium let loose …

So he stood behind it like a Roman shield that he carried with him. It was Plexiglas that he could see through… Anyhow, I finally saw a gastroenterologist. He did an endoscopy. Yes, there was evidence of ulcerative colitis … Crohn’s disease is basically the same inflammatory bowel disease, but it affects the whole digestive tract, where ulcerative colitis is strictly colon and rectum.

So I went on medication. That was difficult, trying to hold an enema of medication when you go to bed every night. So I was glad that my disease went into remission.

At the time, I didn’t understand the significance of the medication … So after the medication worked, I stopped taking it, thinking, oh, goody, that’s over with! Well, it came back with a vengeance and the medication never worked again So I ended up in the local hospital, for a week. They couldn’t bring the inflammation under control with prednisone.

That was the place I received my first injection of opiates, about the fourth day I was in there.

It was a nurse who first introduced Stretch to opioids

The nurse instigated the shot. I think she understood I was pretty miserable and offered me one where nobody else had. And of course I was kind of like, “I guess.” And she’s, “Okay I’m going to get you one.” So she comes back with a shot and gives it to me.

And it seemed like forever later, just sitting on the edge of the bed in the same exact spot that I was, after I sat up after she gave me the injection. It just kind of totally zoned me out.

It zoned me out, but it was an escape from the reality of my situation at the time, even though I didn’t understand it as such. I just zoned out. So it kind of gave me a mental and physical respite that I probably didn’t even recognize that I was getting at the time.

But it wasn’t a sense of “I want that again” or “Oh, I need to have that.” I just noticed something strange happening with the passing of time over this period. I realized I was loopy. But the notion that all this time had passed and I couldn’t recall being miserable during that period was interesting.

I ended up going to the Cleveland Clinic.

Robert J. Marks: Now, the Cleveland Clinic has an incredible reputation.

Stretch: Yes. At the time they were one of the best, probably next to Mayo Clinic, the next best place to go in the country for bowel surgery, colorectal surgery. And there was a gentleman from Australia there, Dr. Fazio, who had developed a fine program that they were proud of and that drew a lot of support. So off I went, transferred at night in an ambulette [a wheelchair delivery van].

Robert J. Marks: Okay. So you went to the Cleveland Clinic and you had an operation.

Stretch: I ended up having an emergency colectomy. It was kind of taken out of my hands. The surgeon said, “You’ve got to do this, or it could rupture and you might die.”

(In the operation, the surgeon removed Stretch’s entire large intestine, leaving him with an ileostomy for the remaining small intestine. It was the first of three surgeries.)

Robert J. Marks: Okay. Now, when you did this, again, that was clearly a lot of pain, and there were probably more opioids.

Stretch: Yes. And interestingly, at the time, of course, I had pain medicine for the surgery and after. My pain was bad, but it wasn’t excruciating. They gave me opiates until it was time to go home. They gave me a modest amount of opiates. I believe they actually had tapered me off the opiates before they let me leave the hospital.

Robert J. Marks: Dr. Hurley, when I was talking to him, said that during surgery, he pumps enough Fentanyl into patients to kill them. But they’re in the operating room and so, the breathing apparatus takes over. So you went through an experience like that, I suppose.

Stretch: Yeah. And you wake up in the recovery room and the nurse would assess your pain, if I recall. I’m awful groggy and they would administer more if you needed it, kind of assess based on your feedback.

Robert J. Marks: Did they give you one of these little push buttons? …

Stretch: I do believe I had a pump with a button. It’s self-initiated, but it won’t give you any more medication than the doctor has told it, it can give you.

But the important thing there was, is when I checked out, they were very adamant to me about not using opiates, unless I absolutely has to. It was Percocet at the time, common just everyday Percocet. They were very direct: “Don’t use this if you don’t need to.” And I didn’t feel like I needed to. And I heeded the warning so I used ibuprofen.

Robert J. Marks: Not an opiate.

Stretch: For the most part, I used ibuprofen. After I was home, there were a couple nights where I chose to take some of the opiates and I hated the way it made me feel. I mean, it bothered me. I couldn’t sleep and things were irritating. So I was deterred from taking it…

But Stretch found that the opiates had a curious way of worming their way into his pain regimen despite everything

Robert J. Marks: Okay. Would you say you were in any way addicted?

Stretch: Interestingly, I didn’t know it at the time. But after having been on them in the hospital and come home, I was really having a hard time sleeping. I was fidgety and my arms would ache and it’s like, what is going on? And after I ended up dependent and addicted, I understood what was happening at that time. And I actually ended up calling, I was so disturbed, I called one of the doctors at the Cleveland Clinics, “What’s going on?” From the withdrawal effects that I didn’t understand that I was experiencing, I was experiencing them as just like a panic psychological problem.

Robert J. Marks: You did have withdrawal symptoms, but you really didn’t identify them with the opioids.

Stretch: Yeah, I didn’t know that’s what it was.

Next: After the second surgery, Stretch got even more friendly with opioids.

Here are the all three parts of the episode:

Some opioid addictions begin in the hospital “Stretch” tells Robert J. Marks how he became addicted to medical doses of opioids while seeking relief from pain stemming from operations. Stretch discovered Hebbs’ Law, “Neurons that fire together wire together” the hard way when he became addicted. Later he found that it can be reversed.

Medical opioids: The war between chronic pain and addiction “Stretch” tells Robert J. Marks, the surgeries did not really work and he became addicted to the painkillers while trying to live a normal, working life. When Stretch started in recovery, he met dentists, anesthesiologists, and nurses who were addicted to medical opioids too — as well as former Death Row inmates.

and

How “Stretch” finally kicked the medical opioid habit. It wasn’t easy but it was the high cost of staying alive while managing his chronic medical disorder. Stretch’s advice to kids who’d like to try opioids: “Maybe you’d want to try some skydiving without a parachute or cliff climbing without any ropes…”

You may also wish to read:

Opioids: The high is brief, the death toll is ghastly. Fentanyl has medical uses in, say, open heart operations where the patient is on life support; otherwise, it is a one-way ticket off the planet. Anesthesiologist Richard Hurley tells Robert J. Marks how Fentanyl affects the brain and why the street version is so deadly.

and

What anti-opioid strategies could really lower the death toll? Anesthetist Dr. Richard Hurley discussed with Robert J. Marks the value of cognitive behavior therapy — reframing the problem. Life expectancy in the United States is decreasing due to opioid deaths, though the problem is now primarily street drugs, not medically prescribed ones.

Show Notes

- 03:19 | Introducing Stretch

- 03:54 | Failed Surgeries and the Beginning of an Addiction

- 26:28 | Fentanyl Lollipops

- 29:45 | Withdrawal Becomes the Motivator

- 34:39 | The Difficulties of Detoxing

- 44:45 | Advice for those Undergoing Surgery

Additional Resources

- More information about Dr. Robert J. Marks

- Podcast with Dr. Richard Hurley on opioid addiction: Exercising Free Won’t In Fentanyl Addiction: Unless You Die First

- More information about Oxycodone (OxyContin, Percodan)

- More information on fentanyl