Opioids: The High Is Brief, the Death Toll Is Ghastly

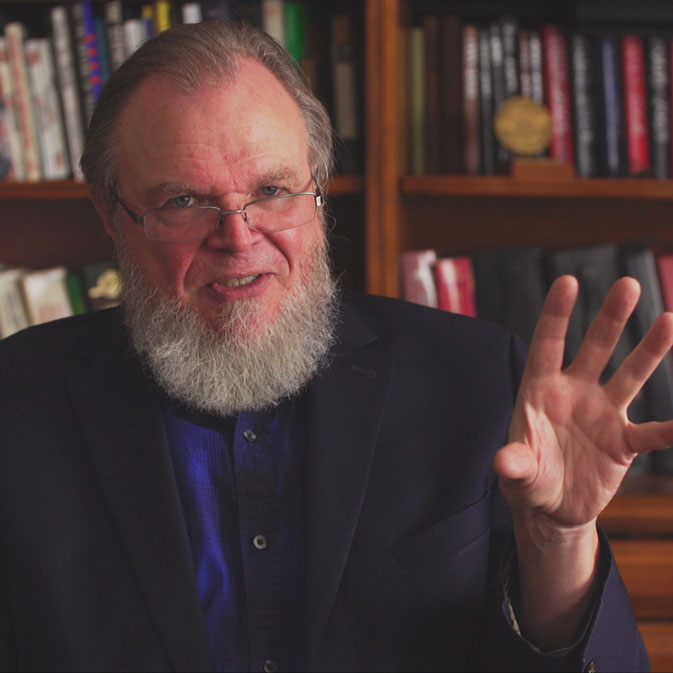

Fentanyl has medical uses in, say, open heart operations where the patient is on life support; otherwise, it is often a one-way ticket off the planetIn a recent podcast, “Exercising Free Won’t in Fentanyl Addiction: Unless You Die First” (May 4, 2022), Walter Bradley Center director Robert J. Marks interviewed anaesthesiologist and pain management expert Dr. Richard Hurley on how highly addictive opiods like Oxycontin, Percodan, and Fentanyl act on the brain. Between April 2020 and April 2021, misused opioids killed over 100,000 Americans. Opioids like Fentanyl have a use in medicine but they are easy to get and subject to abuse.

Note: Robert J. Marks, a Distinguished Professor of Computer and Electrical Engineering, Engineering at Baylor University, has a new book, coming out, Non-Computable You (June, 2022), on the need for realism in another area as well — the capabilities of artificial intelligence. Stay tuned.

This portion (the first half of the episode) begins at approximately 02:48 min. A partial transcript and notes, Show Notes, and Additional Resources follow.

Robert J. Marks: Before we speak to our guest, here’s a little bit of background about the brain chemistry of addiction from the perspective of neuroscience. In the 1960s, neurosurgeon Benjamin Libet noticed a signal in the brain that occurred before you knew you were going to do something. In other words, if you had a sudden impulse to call your mom, there would be a signal in your brain prior to your impulse to call your mother that would say, “Call your mother.” And then it would tell you that you were supposed to call your mother.

On the surface, it looks like you don’t have free will. Your brain generates signals about what you were to do before you knew you wanted to do it. But Libet but noticed that humans do have the ability to say no to these impulses. We don’t have to do what the brain signals tell us to do.

Libet called this ability free won’t …

Anyone who is recovering from an addiction practices free won’t. When I was quitting smoking, my wife Monica kept telling me we were not going to have any kids as long as I smoked. And I wanted to have kids. So as I was quitting smoking, my brain kept telling me, “Smoke a cigarette. Go ahead, Bob. You really want a cigarette.” And I had to exercise a lot of free won’t in quitting my addiction to tobacco.

After a bunch of attempts, I finally quit. And when you quit an addiction, your brain rewires itself away from the addiction. But that path is always there, ready to be rebuilt. Recovering alcoholics are told they must not even take a sip of booze if they want to stay on the wagon. And ex-smokers reinforce their commitment with the mantra, which I was taught: “I am a puff away from a pack a day.” So I wasn’t even to touch a cigarette.

Now, opioids are highly addictive. Oxycontin is a opioid. Percodan is an opioid. Fentanyl, off the street, is an opioid that is killing people but also has some useful medical uses. To talk about addictions, we’re really privileged to have as our guest today, Richard Hurley, a medical doctor who is board certified in anesthesiology and pain medicine…

“Nearly 841,000 people have died since 1999 from a drug overdose.1 In 2019, 70,630 drug overdose deaths occurred in the United States. The age-adjusted rate of overdose deaths increased by over 4% from 2018 (20.7 per 100,000) to 2019 (21.6 per 100,000).” — Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Robert J. Marks: I know you use opioids in your practice. Why are opioids so addictive?

Richard Hurley: There are very few drugs that can actually give you a sense of euphoria or pleasure. But the compound and the molecular structure of the opioids stimulates certain areas of the brain. Now, the receptor that really does this is the immune receptor. Other receptors are also involved throughout the brain.

Robert J. Marks: What is a receptor in the brain?

Richard Hurley: So these are little tiny receptors, almost like a key in a lock. And the molecule itself gets in there. It stimulates this little receptor. And there are little G proteins that are then stimulated. And they then go on to stimulate the receptor, then the nerve. And then those nerves actually go, if it’s in the brain, they’ll stimulate the lateral hypothalamus, the tegmental area in the mid brain. And then they’ll go to stimulate the areas of the acupoints, which are actually basal ganglia. And all of these parts of the brain are heavily modified by dopamine. And dopamine seems to be the pleasure window. There’s also a release of endorphins, which are endogenous morphine-like compounds in the brain. And the two of them together in high amounts will produce euphoria.

Richard Hurley: And then what’s really interesting is that this pleasure sensation is then transmitted to the prefrontal cortex, which makes you remember it all. Hence the reason why that memory is never erased and that’s why one puff is one pack. I remember Mark Twain said quitting smoking was the easiest thing he’d ever done. He did it a thousand times.

Robert J. Marks: Yep. That’s me. I did it a thousand times, too. So I have talked to some people, in fact, a very, very close friend, who was addicted to Fentanyl. And it started with medical procedures. And, I guess, the Fentanyl comes in little lollipops and stuff like that. And he confided in me that he never took the opioids to get that high, that he just took the opioids so he could feel normal. So this feeling of euphoria comes maybe the first few times when you take this and then all of a sudden your body craves it. And just to feel normal, he had to take his Fentanyl.

Richard Hurley: That is very true. And we see that also in prescription drugs, where I just don’t feel normal unless I take it. But in prescription medications, especially short-acting ones, is that they go through a sense of withdrawal every four to six hours as the drug wears off…

Robert J. Marks: We hear about the street drug Fentanyl, which is an opioid killing so many people. What’s happening here?

Richard Hurley: It’s a synthetic. The molecular formula of Fentanyl is very similar to heroin. It’s a unique analgesic. That is, it’s extremely powerful. Given by IV, it is a hundred times stronger than morphine and 50 times stronger than heroin. The problem with the drug is that you get an intense high — no question about it, a euphoric state. That euphoria, though, like you mentioned, as you continue to use it is not the same.

But the therapeutic window of this drug is critical. In other words, if I give you an overdose of heroin or morphine, we’ve got about an hour to give you Naloxone or Narcan to reverse that. It’s an antidote. And then all of a sudden you’ll start breathing again. With Fentanyl, if you don’t get to the patient with IV Fentanyl, within minutes, they’ll be dead.

Robert J. Marks: Oh, my goodness. I was reading about the street Fentanyl that’s available in the authority for all facts, People Magazine. This was from the April 18th, 2022 edition, “The Faces of Fentanyl.” And they had a hundred pictures of people who had been killed through Fentanyl.

I guess, it’s a big problem in the U.S. They said drug overdose deaths were up by nearly 30% last year. In Milwaukee County, they say there has been 234% increase in drug-related deaths in the past 10 years. And it’s cheap to make. Like you mentioned, was a hundred times stronger than morphine. The DEA seized 9.6 million of these pills in 2021. And 73% of the drug-related deaths in the United States are due to Fentanyl. That is astonishing.

They say two milligrams is the amount of Fentanyl that can kill an adult. Is that… ?

Richard Hurley: 200 micrograms or two-tenths of a milligram is enough to kill anybody. That’s a very small amount. Now, you understand, I was first using Fentanyl when I was an anesthesiologist.

Robert J. Marks: So you use Fentanyl in your practice, right?

Richard Hurley: If you could see how much Fentanyl I give a patient who had open heart surgery, it would scare you to death. But as long as I take over their pulmonary aspects, in other words, as long as I intubate the patient, put them on a ventilator, keep their carbon dioxide levels 40 or less…

Robert J. Marks: Oh, you have instrumentation there that takes over…

Richard Hurley: Right. In other words, I’ll put an intratracheal tube in there. I’ll hook you up to a ventilator. I’ll set the ventilator dose based on your tidal volumes and how often you breathe. I’ll make sure your oxygen levels and CO2 levels are normal. Then we do the operation and you have no pain at all. In other words, they crack your chest and your heart rate and blood pressure doesn’t change a bit. So it’s a very powerful drug, but certainly, it’s utilization in anesthesia is just fantastic.

Robert J. Marks: Now, the obvious question, if you use the Fentanyl in the anesthesia, do the patients have any withdrawal after they come out of their operation?

Richard Hurley: That’s a great question. And the reason I say that is because the drug has a half-life of 30 minutes to an hour. That’s all. I mean, it’s gone. It is so rapidly metabolized and excreted primarily through the urine that you’ll have to actually give them postoperatively some pain medicine, either Fentanyl or whatever. And the Fentanyl can be given either in a bolus or you can set it up in a pump and it’ll deliver so many micrograms per hour.

Robert J. Marks: I see. So even the people that take this drug recreationally only have a short period of being high. Is that right?

Richard Hurley: That’s right. With IV, its half-life is about 30 to 60 minutes. Intramuscularly it might last a little bit longer, but not much more than that. That’s about it.

Meanwhile…

Next: What anti-opioid strategies will really help

You may also wish to read: How a neuroscientist imaged free will (and “free won’t”). At first, Libet thought that free will might not be real. Then he looked again… Neuroscientist Benjamin Libet (1916–2007), who studied measured brain activity as people make decisions, came across the power of “free won’t”: an apparently free decision NOT to do something we had decided on earlier.

Show Notes

- 02:48 | Introducing Dr. Richard Hurley

- 03:04 | What Does It Mean to be Board Certified?

- 06:09 | Why Are Opioids so Addictive?

- 09:07 | The Horrors of Detox

- 14:30 | Has There Been Pushback by the Medical Community?

- 21:32 | Issues with Fake Pills

- 24:27 | Advice for the Addicted