Did Alan Turing’s Change of Heart Set AI on the Wrong Path?

Erik Larson, author of The Myth of Artificial Intelligence, thinks Turing lost track of one really important way minds differ from machinesIn the earlier part of this episode of “Hyping Artificial Intelligence Hinders Innovation” (podcast episode 163), Andrew McDiarmid interviewed Erik J. Larson, author of The Myth of Artificial Intelligence (Harvard University Press, 2021) discussed the big switch in computer science, roughly around 2000, from deductive to inductive logic — because Big Data made inductive logic more productive. Now they look at what machines still can’t do:

This portion begins at about 12:39 min. A partial transcript and notes, Show Notes, and Additional Resources follow.

Andrew McDiarmid: I found some of your podcasts on the web and in one of them you say, “I don’t know what a mind is, but I know what a machine is.” So how does that assertion illuminate where we are on the AI debate?

Erik Larson: I get this question a lot and it’s an understandable question… I deliberately avoided asking those in the book because, as a computer scientist, I wanted to write an argument for computer scientists that was also understandable by the broader public…

So the book was really an exposition of the three known types of inference, deduction, induction and abduction. Basically, the entire field of AI since its inception in 1956 was divided between deductive attempts and inductive attempts which have basically dominated the last 20 years, and there’s been essentially no progress on abduction.

Abduction is common sense thinking. It’s what we do when we have a conversation like we’re having now. It’s what we do when we navigate in dynamic environments, like we go buy a gallon of milk at the store. That’s just completely absent from the work that we do as computer scientists. In fact it’s not even that it’s absent and we haven’t gotten to it yet, it’s that … I could tell you this as someone who builds and designs these systems, nobody even knows. Like nobody has a clue of how to do abduction.

Note: To recap, deduction is logical reasoning: All cats are felines. Tom is a cat. Therefore Tom is a feline.

Induction is reasoning our way to a conclusion via evidence: “In the past, ducks have always come to our pond. Therefore, the ducks will come to our pond this summer.” There’s no guarantee ducks will come but it is a reasonable conclusion based on the evidence.

Abduction is forming a conclusion from known but less-than-certain information. “In an everyday scenario, you may be puzzled by a half-eaten sandwich on the kitchen counter. Abduction will lead you to the best explanation. Your reasoning might be that your teenage son made the sandwich and then saw that he was late for work. In a rush, he put the sandwich on the counter and left.” – Merriam–Webster It is sometimes called an inference to the best explanation.

Erik Larson: I don’t have extremely strong views about what’s going on with the mind, whether it’s a Cartesian model or it’s some kind of other model. What I do know is that our attempts to program the mind in computers have failed and there is a very strong principled reason that they have failed. It does seem like we’re dealing with two different things.

What was Alan Turing’s change of heart about?

Andrew McDiarmid: Right. Keeping mind and machine separate in our minds is, I think, one of the first steps to really having the perspectivet to even get to the right questions in this debate.

Part One of your book is called The Simplified World, where you explain how AI culture has simplified things about humans, and also maybe overextended ideas about technology. You say it started with [British computer pioneer] Alan Turing. Has it really come so far up to today? Are we still doing what he did? Like assuming more than we should?

Erik Larson: His idea was that the intelligence reduces to problem-solving basically. In the book, I talk about how he seems to have undergone a fairly fundamental change. In his earlier work he talked about the distinction in mathematics between ingenuity and insight. Insight was something, he said, that mathematicians use that’s outside of the formal system that they’re working with, to decide on what parts of the system are interesting to think about. So when some mathematician comes up with a new proof or interesting development of some aspect of mathematics, Turing originally was saying that that’s a non-mechanical feature of the mathematician… Ingenuity was the actual working out, the sort of nuts and bolts working out of whatever you’re trying to do in math.

Then later, he seemed to just ignore or effectively jettison that distinction from his discussion. Circa 1936, you have Turing talking about these seemingly non-mechanical and mechanical aspects of doing mathematics… and then by 1950 when he wrote the seminal paper which gave rise to the Turing test, — the conversation test that everybody knows about — he just had completely abandoned this idea. He had clearly come to the view that we could just program, that intelligence is just problem-solving. So if we solve the problem of human intelligence, if we just write it down in computer programs, then there wouldn’t be any difference between the mind and the machine.

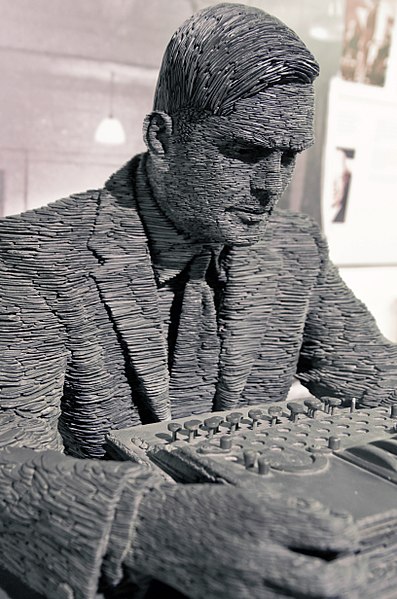

commissioned by Sidney Frank,

built from half a million pieces of Welsh slate/

Antoine Tavenaux, Creative Commons 3.0

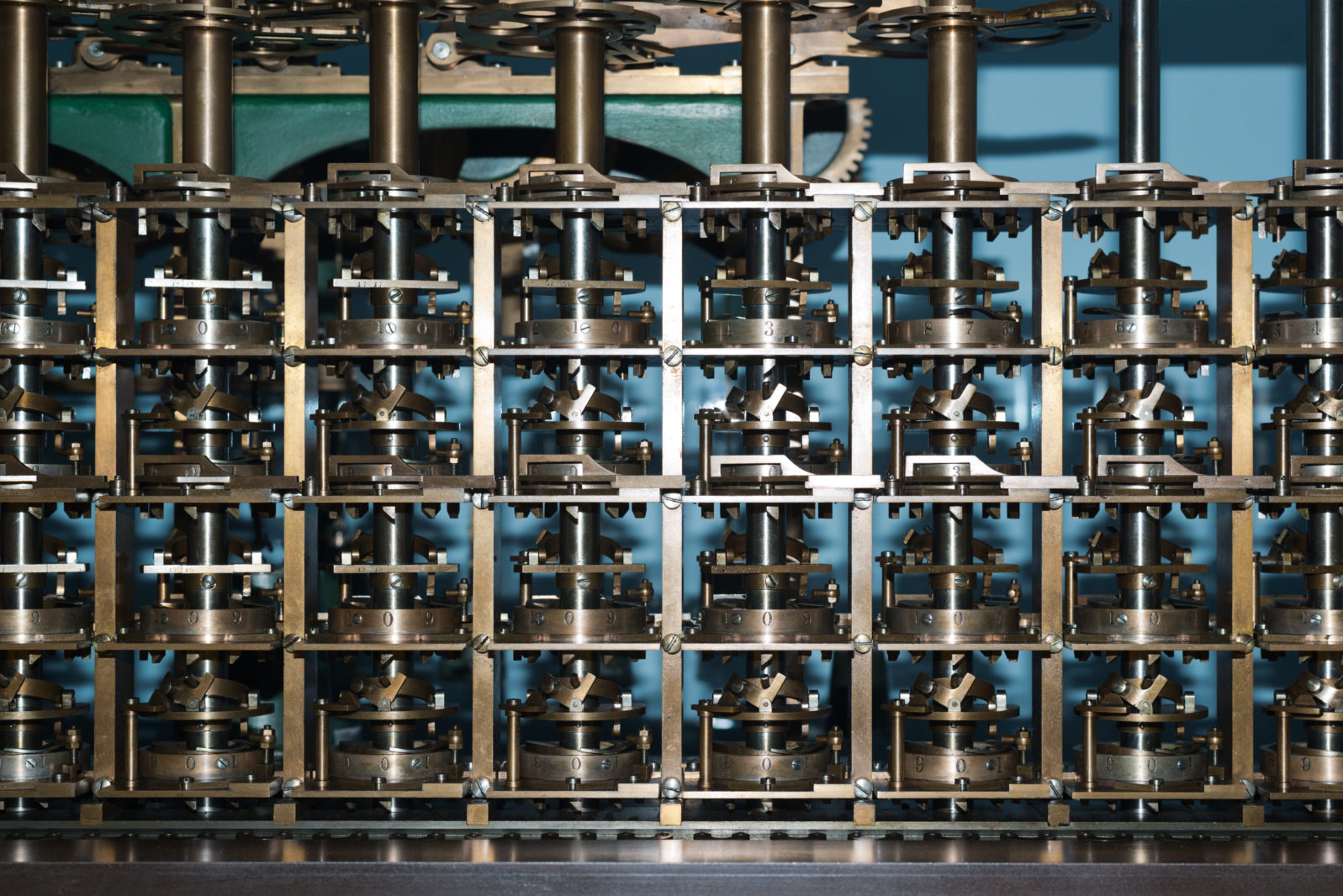

He had this change of heart clearly in his work and I definitely think that he’s kind of the pioneer and the major figure that all of us in AI look back to. He formulated the actual mathematics of what a computer program is. It’s a Turing machine, which is a kind of abstraction, right? And all of computer science rests effectively on this formalism called after him, the Turing machine. So he really is the linchpin for the development. So we look to him as kind of like the father of AI really — and his idea I think was fundamentally flawed.

That’s not to take away from his brilliance as a mathematician; he was a mathematical logician — which is one of my fields that I studied — and he really deserves to be in the annals of history as this brilliant guy. But in terms of his view of human intelligence, I think he had a kind of reductionistic view of human intelligence that was inherited by the field through the decades on up to the current view. And I think that’s unfortunate. That’s what I mean by the simplified world, a simplified reductionistic view of the human mind, of human thinking.

Andrew McDiarmid: Are we still focused on inductive? How do we get to abductive? Is it possible to get to that in AI? You obviously don’t know the answer but you can surmise.

Erik Larson: So the problem with induction, of course, is that you can’t deal with exceptions.

Big Data AI just is what we mean by AI today. It’s all the tech that’s running on your phone, it’s Alexa that interprets the signal from your voice into text sequences, and Siri and so on when you have voice-activated stuff on your phone. It’s movie recommendations on Netflix, it’s automatic recognition of your friends’ faces on Facebook… As an all-encompassing method to generate intelligence, it’s not adequate. Very obviously not adequate. It just doesn’t handle exceptions. So anything new that comes along is going to be a major problem for an inductive system.

Note: Larson offered the example of a black Australian swan in a system where swans are assumed to be white. Machine learning does not handle such exceptions well. It may see a chihuahua as a muffin, for example — a mistake a human would not likely make.

Is Big Data choosing our movies now?

Andrew McDiarmid: And that would seem to be why different organizations that use this technology are constantly wanting feedback from you. They want that thumbs up or thumbs down. They want you to rate the last thing that you bought on Amazon or the last movie you watched because that will update their ability to account for exceptions or just a larger data field.

Erik Larson: Our preferences in the future do likely have some connection to our preferences in the past. But it’s very un-useful for things that require any kind of insight, going back to Turing’s original idea. So if there’s some new movie that comes along that’s not in the dataset, then it just is going to ignore it. So induction is a blunt instrument that looks at the overall scope of prior cases to determine future cases. If you try to use that as a way to generate a true AI general intelligence, it’s just absolutely hopeless.

Even this conversation we’re having now is just full of exceptions and requirements for you to make slight hypotheses and leaps and guesses about meaning and so on. You can’t have just ingested a million prior conversations to figure out what to say next. That just won’t work. You actually have to understand what’s being said now and induction just doesn’t give us that kind of capability.

Andrew McDiarmid: And that’s interesting because you see Netflix pouring money, lots of money into new content, and they actually are using Big Data to figure out what to make next. So again, that can be tricky too. Because if people just watch it because it’s there, are they watching it because it’s there or is it there because they want it? …

Erik Larson: [T]oo much of this AI technology, just inserted and just deployed everywhere, is really pulling against that happening. One obvious example is that the AI systems that the studios are using are not going to recognize anything that wasn’t a formula. So we just know we’re getting formulaic movies if they’re using these AI systems, right? But we can draw a direct line through this, right? From the fact that the AI used today is inductive in its central commitment, and induction relies on prior examples, from that fact, you draw all of these negative consequences about we are now using formulas. Like what worked in the past is going to be the most frequent blockbusters, the ones with … Just on a bell curve, the ones that worked in the past. So all of the surprise hits are going to fall out of that… they won’t be as likely.

It’s effectively repainting Hollywood as being more Hollywood, more formula and less really interesting stuff. The same with publishers in fiction and so on. It’s troubling. I actually don’t deal with this in this book but I’m glad that you asked this question. I talk about how using computers to try to do core science is a foolish game and that’s a related issue with the question of innovation.

Next: Big Data doesn’t create new ideas, it entrenches the old ones. Copernicus could tell you how that works.

Here is the whole discussion:

- How AI changed — in a very big way — around the year 2000 With the advent of huge amounts of data, AI companies switched from using deductive logic to inductive logic. Erik Larson, author of The Myth of Artificial Intelligence (Harvard 2021), explains the immense power using inductive logic on Big Data gave to Big Tech firms.

- Did Alan Turing’s change of heart set AI on the wrong path? Erik Larson, author of The Myth of Artificial Intelligence, thinks Turing lost track of one really important way minds differ from machines. Much interaction between humans requires us to understand what is being said and it is not clear, Larson says, how to give AI that capability.

- Why Big Data can be the enemy of new ideas. Copernicus could tell us how that works: Masses of documentation entrench the old ideas. Erik Larson, author of The Myth of Artificial Intelligence (2021) notes that, apart from hype, there is not much new coming out of AI any more.

- Understanding the de facto Cold War with China High tech is currently a battlefield between freedom and totalitarianism. At a certain point, Andrew McDiarmid thinks, it’s time to just turn it all off. But then, what’s left?

You may also wish to read: Harvard U Press Computer Science author gives AI a reality check. Erik Larson told COSM 2021 about real limits in getting machines that don’t live in the real world to understand it. Computers, he said, have a very hard time understanding many things intuitive to humans and there is no clear programming path to changing that.

and

Silicon Valley insider: Why friendly super-AI won’t happen Venture capitalist Peter Thiel talks about the Great Filter hypothesis: Why should we assume a superior artificial intelligence would be friendly? Thiel argues that, assuming that AI that “can do everything we can do” were created, there is no reason to expect it to be friendly — or even comprehensible.

Show Notes

- 00:44 | Introducing Erik Larson

- 01:59 | What is the AI Landscape?

- 04:03 | How did Erik become interested in AI?

- 12:39 | Mind and Machine

- 16:40 | The Simplified World

- 20:48 | Different Types of Reasoning and AI

- 29:53 | Lessons from the Past

- 34:02 | The Human Brain Project

- 38:23 | AI in the Future

- 42:27 | AI and Big Tech

- 53:58 | Turn it Off

- 57:41 | Stuck in the Modern World

- 58:51 | Human Exceptionalism

Additional Resources

- Buy Erik Larson’s book: The Myth of Artificial Intelligence.

- Andrew McDiarmid at Discovery.org

- Erik Larson at Discovery.org

- The difference between deductive, inductive, and abductive reasoning.

- The Alan Turing Machine

- The Turing Test

- The Human Brain Project

- Buy Shoshana Zuboff’s book: The Age of Surveillance Capitalism

- Buy Jaron Lanier’s Ten Arguments for Deleting Your Social Media Accounts Right Now