China: COVID-19’s True History Finds an Unlikely Home — GitHub

The Chinese Communist party, rewriting the COVID-19 story with itself as the hero, must reckon with truthful techiesFor a brief window of time at the beginning of 2020, China’s internet censors didn’t block stories about Wuhan and COVID-19, the coronavirus.

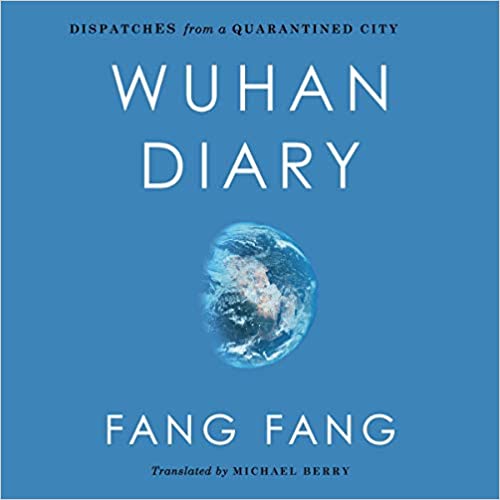

Caixin, a widely-read news magazine, published a multi-page investigative report on everything leading up to the outbreak, including the way in which the provincial authorities in Hubei, of which Wuhan is the capital, suppressed knowledge of the virus. Fang Fang, an award-winning novelist, kept a Wuhan diary online on Weibo, which was recently published as a book in the U.S. (HarperCollins 2020). For that short time, comments on the coronavirus were not being censored (Wired) at WeChat. Many people were thus able to vent their frustrations and pay their respects when 32-year-old ophthalmologist and whistleblower Li Wenliang died from the virus.

Then those stories disappeared. Government censors started wiping the internet of information on the coronavirus in Wuhan. They also began a campaign to rewrite the history, making China’s authoritarian government the hero of the tale rather than one of the factors in the virus’s spread.

However, Chinese netizens are clever. They’ve been testing boundaries and circumventing internet censors for years. Some of them retold whistleblower Dr. Ai Fen’s revealing interview (which authorities were trying to erase) via emojis and Morse code. Others stored information in a Minecraft setting.

One unlikely home for uncensored coronavirus testimonials is a programmers’ site called GitHub.

Why Is GitHub Important to Free Speech in China?

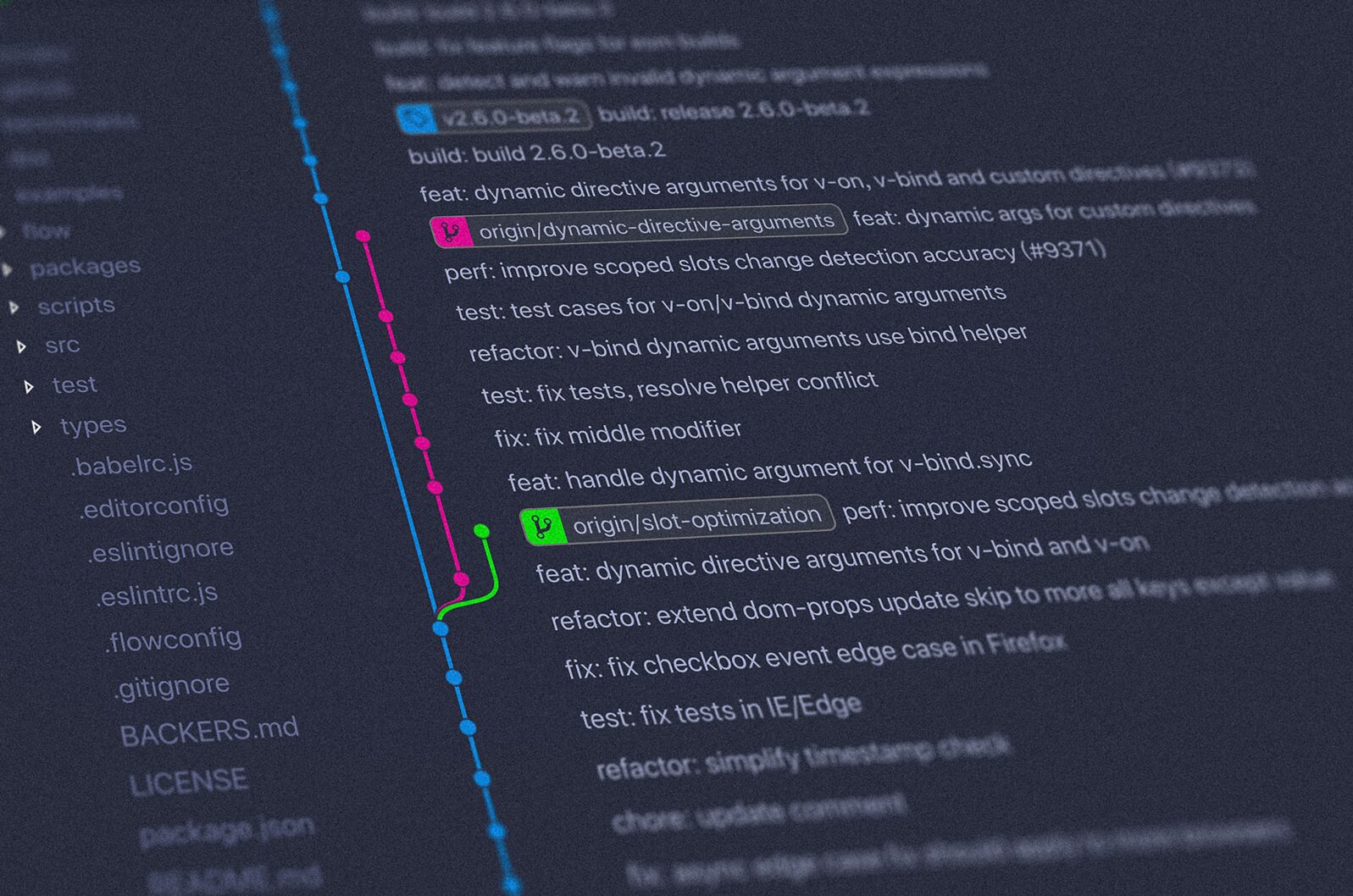

GitHub is an open-source online tool used by computer programmers and software developers to keep a record of every change made by anyone while working on a project. The biggest advantage GitHub offers programmers is the ability to revert back to older versions (version control). Should anyone make a fatal change to a massive computer program, the programmers can go back to an older version without losing time on the project fixing the error. This is an even more powerful safeguard when multiple users are working on a project.

GitHub is by far the biggest version-control collaborative software in use in the tech industry, with more than 30 million users. When China tried to censor it in 2013, the tech sector complained that such actions would set back China’s technology industry. The Chinese government relented and allowed access to GitHub within its Great Firewall. GitHub, therefore, has been deemed the “last land of free speech in China.”

That is partly due to GitHub’s design:

Chinese authorities cannot censor individual projects, because GitHub uses the HTTPS protocol, which encrypts all traffic. But they are also unwilling to ban GitHub entirely, because it is invaluable to the Chinese tech industry.

Yi-Ling Liu, “In China, GitHub Is a Free Speech Zone for Covid Information” at Wired (September 9, 2020)

In short, GitHub exemplifies the balancing act that the Chinese government has been performing for the last two decades: “Can it keep the internet just free enough to nurture economic growth but not so free that it opens the door to political instability?”

How the Techies Get Around the Censors

Each GitHub project has its own online repository (“Repo”). The Chinese government’s censors temporarily blocked GitHub in 2013 on account of Repo “996.ICU.” That one housed information and complaints by Chinese citizens working in the tech sector regarding their grueling work conditions. The name is an acronym: “Working 9am to 9pm, six-days-per-week will send you to the intensive care unit.” Other projects that censors have targeted include the GreatFire repository which distributes anti-censorship software.

More recently, several repositories have been created to store news articles, interviews, and other censored information about the coronavirus, including personal accounts of living in lockdown. Those repositories include “Coronavirus stories,” “#2020nCovMemory,” and “2020nCov_individual_archives.” Terminus2049 housed a copy of the interview with Dr. Ai Fen, who first reported the coronavirus in December 2019.

Wired interviewed a PhD candidate in the United States, Weilei Zeng, who routinely uses GitHub for research projects. As the pandemic progressed, he found repositories where thousands of Chinese netizens stored content they had found online before it was taken down. He commented, “It made me feel much more at peace, knowing that these stories were being saved somewhere” and he became a contributor to the 2020nCoV_individual_archives repository, uploading stories about the coronavirus from Chinese sites such as WeChat and Weibo.

When novelist Fang Fang had her daily Wuhan diary taken down by censors, her posts were stored in #2020nCoVMemory. However, this repository has since been changed from “public” to “private” by its creators. They were responding to the fact that three individuals who had contributed to the Terminus2049 repository were arrested in Beijing:

On April 19, three volunteers of a GitHub site, terminus2049, reportedly lost contact with their families. And on Saturday, it was confirmed that at least two of them, Cai Wei and his girlfriend surnamed Tang, had been put under residential surveillance at a designated location (RSDL) by the Chinese police.

Cai and Tang’s families have received official notification from local police station in Beijing City, but the family members of the third person, Chen Mei, has not received any official notification about the whereabouts of Chen.

William Yang, “China’s crackdown on COVID19 content continues as three volunteers were arrested in Beijing” at Medium (April 27, 2020)

The creators of #2020nCoVMemory assured users that they had changed the settings for security reasons and that users are still safe. They hope to change the project back to “public” when possible.

Chinese Human Rights Defenders, an organization that promotes peaceful grassroots activism in China, has documented online 897 cases of Chinese netizens who were “penalized by police for their online speech or information sharing about coronavirus between January 1 and March 26, 2020.”

Wanted: An internet that is not really the internet

Because governing bodies are hesitant to just block GitHub, several countries will contact GitHub and request that “illegal” content be removed from the site. GitHub, in keeping with the original creators’ commitment to transparency, puts all government requests to remove illegal information into a repository at https://github.com/github/gov-takedowns. Most are translated using Google Translate. Furthermore, while GitHub may remove content from one country, it does not remove material from all geographic regions.

This approach does not meet the Chinese government’s desire to control online content. Thus, China is creating its own version of GitHub, called Gitee. The government promotes Gitee as the open-source version control software for the Chinese tech world. Gitee would operate independently from GitHub and, as is the case with all businesses in China, the government will have greater control over how Gitee is used (TechCrunch).

There is also talk of GitHub starting a separate subsidiary in China that complies with censors. Microsoft, which bought GitHub in 2018, has been more willing than other Silicon Valley businesses to work with China’s censors:

If it came down to such an ethical trade off—between erasing China’s Covid-19 posts from the digital ether in exchange for access to the country’s open source code, between the preservation of a collective history and the advancement of technological progress—what decision would Microsoft make? What would be gained, and what would be lost?”

Yi-Ling Liu, “In China, GitHub Is a Free Speech Zone for Covid Information” at Wired (September 9, 2020)

The question assumes, of course, that there is no organic connection between the preservation of a truthful history and technological progress. Many tech thinkers would take issue with that assumption.

The Stories We Tell Ourselves

Author and journalist Peter Hessler wrote an extensive piece in The New Yorker about his nine days interviewing people in Wuhan about their experience during the lockdown. His subjects included Fang Fang, whose book is available in the U.S. but not in China. Every writer he spoke to in Wuhan spoke highly of Fang Fang and they were also protective of her:

When Fang Fang’s Weibo account was suspended, a number of tech-savvy young Chinese helped her find other ways to post material. And there were indications that some people in high positions also valued her. Fang Fang said that an upper-level editor at Weibo eventually wrote her a private letter apologizing for the censorship.

Peter Hessler, “Nine Days in Wuhan, the Ground Zero of the Coronavirus Pandemic” at The New Yorker (October 5, 2020)

Fang Fang has faced online vitriol and death threats for her stories from Wuhan about “overcrowded hospitals turning away patients, mask shortages and relatives’ deaths.” (Hong Kong Free Press) She has responded to detractors by pledging to donate her royalties to the families of front line workers who have died of COVID-19.

Hessler met journalists who were only permitted to write positive stories about Wuhan who nonetheless kept files of articles about people who had lost loved ones and about the trauma from the lockdown. One offered to tell the story in ten years if the climate has changed. Hessler believes that the truth of what happened in Wuhan will eventually come to light but that, for now, the Communist Party is strictly censoring any information about Wuhan to ensure that it controls the narrative:

Throughout the Communist era, there have been many moments of quarantined history: the Great Leap Forward, the Cultural Revolution, the massacre around Tiananmen Square. In every case, an initial silencing has been followed by sporadic outbreaks of leaked information. Wuhan will eventually follow the same pattern, but for the time being many memories will remain in the sealed city.

Peter Hessler, “Nine Days in Wuhan, the Ground Zero of the Coronavirus Pandemic” at The New Yorker (October 5, 2020)

Not all of the memories are sealed in the city, however. Some are stored in clever ways online. GitHub is probably just one of them.

Here are some of Heather Zeiger’s earlier articles on what we’ve been able to learn about COVID-19 in China:

Censorship? But Coronavirus Doesn’t Care!

Coronavirus in a World Without Trust

China: Rewriting the History of COVID-19

and

COVID-19: Getting to the Bottom of What Happened in China”