William Dembski: Destroy the AI Idol Before It Destroys Us

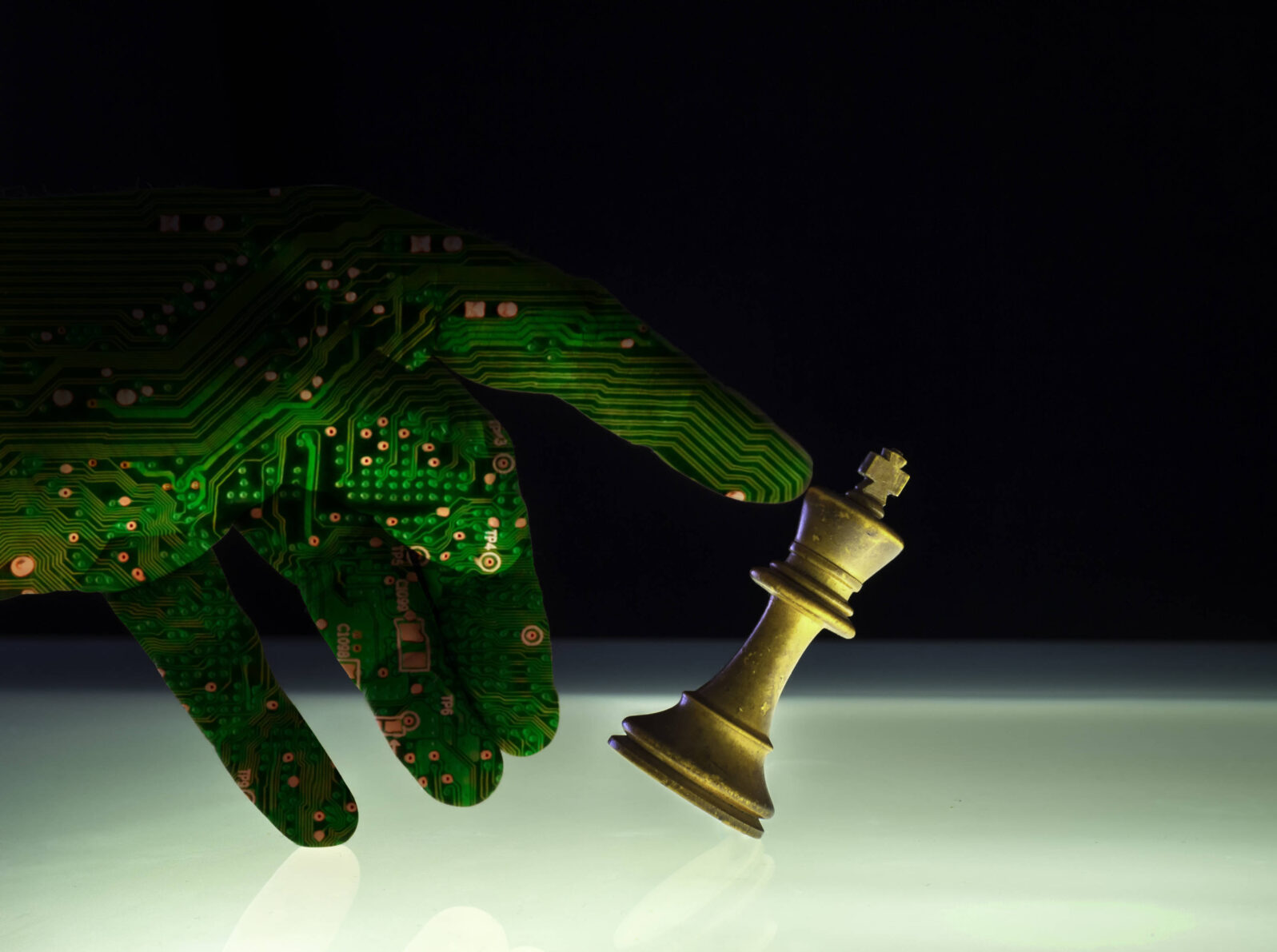

Design theorist Dembski points to the way that chess adapted to computers to become better than ever as a way forward in the age of AIIn the final essay in his series* at Evolution News on the hype around artificial intelligence, design theorist William Dembski offers some thoughts on what it would take to destroy the idol. Here are some highlights:

If we’re going to be realistic, we need to admit that the AGI idol will not disappear any time soon. Recent progress in AI technologies has been impressive. And even though these technologies are nothing like full AGI, they dazzle and seduce, especially with the right PR from AGI high priests such as Ray Kurzweil and Sam Altman. Moreover, it is in the interest of the AGI high priests to keep promoting this idolatry because even though AGI shows no signs of ever being achieved, its mere promise puts these priests at the top of the society’s intellectual and social order.

William A. Dembski, “Artificial General Intelligence: Destroying the Idol,” Evolution News, February 7, 2024

A 2009 film about Ray Kurzweil, Transcendent Man, showcases the idolatry:

A 2011 review at Scientific American picks up on that theme and reviewer John Rennie is not impressed:

The film is about Kurzweil’s belief that within just a few decades technology will allow human beings to transcend the physical and intellectual limitations of their biology. It also paints Kurzweil as a brilliant man who has personally always risen above the skepticism and misunderstanding of his doubters.

Cleverly edited and entertaining, Transcendent Man is unfortunately also too starstruck and reverent toward Kurzweil for its own good. It wants in part to be a movie about ideas, but frustratingly, it refuses to truly challenge any of those it raises—whether supportive or critical of him. Given that the film’s theme is the salvation or destruction of the human race, its lack of commitment to a perspective other than innocent wonder is unsatisfying.

John Rennie, “The Immortal Ambitions of Ray Kurzweil: A Review of Transcendent Man” Scientific American, February 15, 2011

But many people out there choose to be starstruck with innocent wonder at the pronouncements of the high priests of tech rather than ask some hard, pragmatic questions. Their uncritical acceptance is a much bigger problem, going forward, than AI’s computational power. People in that mood are apt to passively accept things they should think about and resist.

So what, specifically, are we to do?

Dembski proposes an alternative approach:

1. Adopt an attitude that wherever possible fosters human connections above connections with machines;

and

2. Improve education so that machines stay at our service and not the other way around.

Dembski, “Destroying the Idol”

He offers chess as an example:

A good case study is chess. Computers now play much stronger chess than humans. Even the chess program on your iPhone can beat today’s strongest human grandmaster. And yet, chess has not suffered on account of this improvement in technology. In 1972, when Bobby Fischer won the chess world championship from Boris Spassky, there were around 80 grandmasters worldwide. Today there are close to 2,000. Chess players are also stronger than they ever were. By being able to leverage chess playing technology, human players have improved their game, and chess is now more popular than ever.

With the rise of powerful chess playing programs, chess players might have said, “What’s the use in continuing to play the game. Let’s give it up and find something else to do.” But they loved the game. And even though humans playing against machines has now become a lopsided affair, humans playing fellow humans is as exciting as ever. These developments speak to our first guideline, namely, attitude. The chess world has given primacy to connecting with humans over machines. Yes, human players leveraged the machines to improve their game. But the joy of play was and remains confined to humans playing with fellow humans.

Dembski, “Destroying the Idol”

He adds that the computers now serve as educators for chess players because they can’t reward sloppy play. In much the same way, a math textbook can’t reward wrong answers, the way a human friend might, accidentally or otherwise.

But, he warns, we face choices:

To the degree that AGI high priests want worshippers for their idol (and they do), it is in their interest to maintain a population of serfs whose poor education robs them of the knowledge and skills they need to succeed in an increasingly technological world. The challenge is not that machines will overmatch us. The challenge, rather, is that we will undermatch ourselves with machines. Instead of aspiring to make the most of our humanity, we degrade ourselves by becoming less than human.

Dembski, “Destroying the Idol”

Much more at the link.

*Note: The series originated as a long essay at his site, billdembski.com,

Here are all the highlights from the series:

Dembski: Does the squawk around AI sound like the Tower of Babel? Well then, maybe that’s just what it is. He sees the breathless and implausible claims for computers that think like people as the modern equivalent of ancient idols. Here are some highlights.

Human intelligence is fundamentally different from machine intelligence. Dembski discusses the problems we will encounter when we try to integrate the two when, say, sharing the road with self-driving cars. He also touches on Ray Kurzweil’s quest for digital immortality and how it falls short of the original quest and its religious expressions.

William Dembski: When is transhumanism a form of technobigotry? In his further essays in the current series, he explains why AI cannot avoid collapse without the input of novel information from humans. AI systems alone go bankrupt, Dembski argues, because intelligence by nature requires novel insights and creativity, which is to say, an oracle from outside.

and

William Dembski: Destroy the AI idol before it destroys us. Design theorist Dembski points to the way that chess adapted to computers to become better than ever as a way forward in the age of AI He warns that the promoters of AI as “taking over” have a vested interest in claims that keep them at the top of society’s intellectual and social order.