Citizen Scientist Forrest Mims Tells His Remarkable Life Story

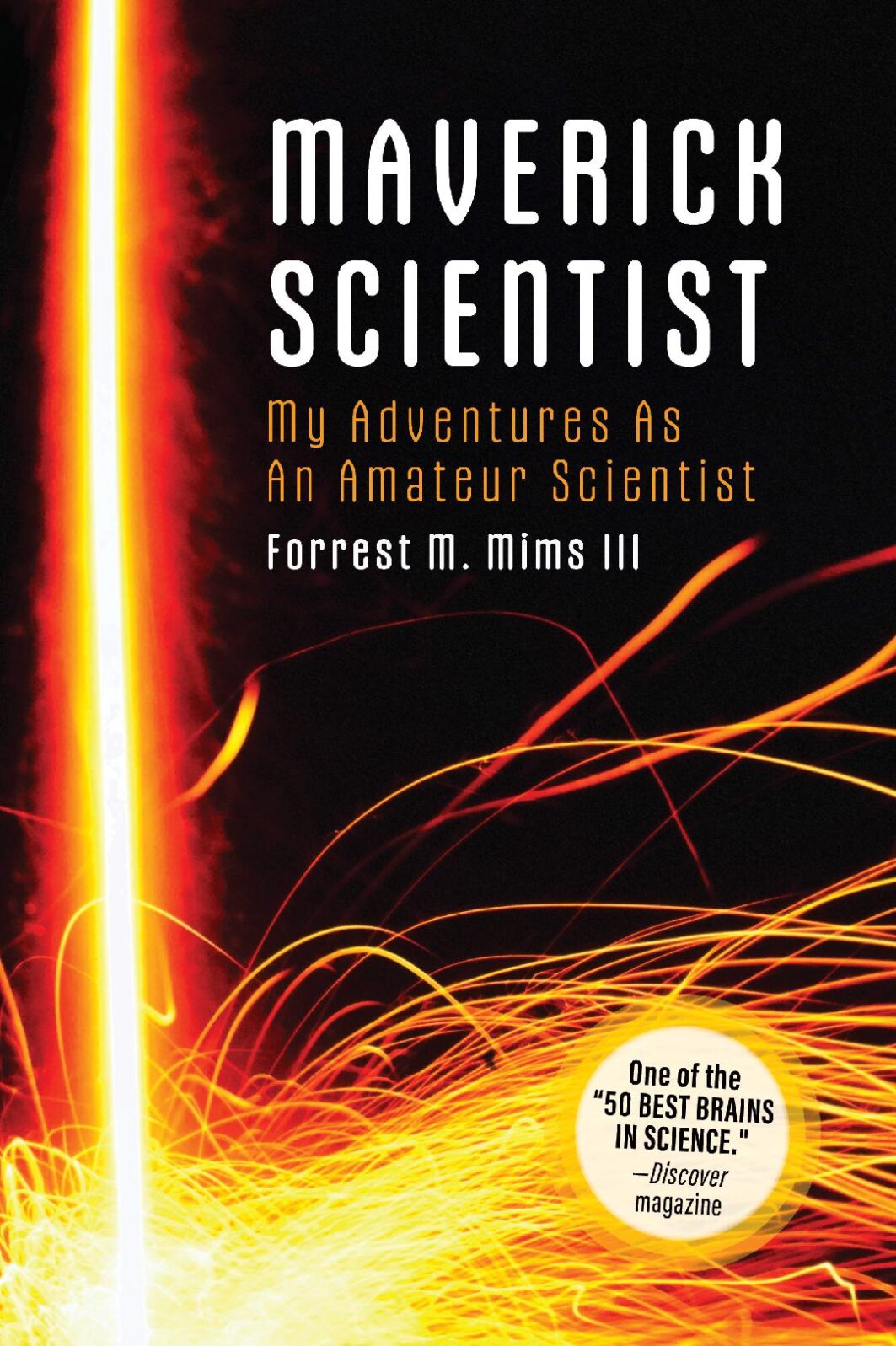

In his new book “Maverick Scientist,” he details the ups and downs of an extraordinarily productive life in science, with few credentials to hide behindForrest M. Mims III (1944–) has so many accomplishments in science and electronics — with little formal training — that they would make your head spin.

Getting Started in Electronics, originally written for RadioShack (now the Source), is one of dozens of electronics books Mims has produced over the years, sold more than 1.3 million copies.

Introducing his autobiography, Maverick Scientist: My Adventures as an Amateur Scientist (Make Community, LLC, April 2024), the publisher notes,

At thirteen he invented a new method of rocket control. At seventeen he designed and built an analog computer that could translate Russian into English and that the Smithsonian collected as an example of an early hobby computer. While majoring in government at Texas A&M University, Forrest created a hand-held, radar-like device to help guide the blind. And during his military service, he had to be given special clearance to do top secret laser research at the Air Force Weapons Lab. Why? Because while he lacked the required engineering degree, they wanted his outside-the-box thinking on the project.

That Scientific American episode…

Mims’s many accomplishments and willing service to science organizations, both in his native Texas and elsewhere, were not what brought him most broadly into the public eye. It was an innocent suggestion on his part to the editor of Scientific American. that he look after the “Amateur Scientist” column, given his background. But when editor Jonathan Piel discovered that he was a Christian, doubted Darwin’s theory of evolution, and was pro-life, things rapidly cooled off. He was told “There’s no question that on their own merits the columns are fabulous. If you don’t do them for us you ought to do them for somebody, because they’re great. … What you’ve written is first rate. That’s just not an issue. It’s the public relations nightmare that is keeping me awake.” The magazine ended up publishing three of his columns instead.

While many people supported Mims, the science elite closed ranks. A snarky Washington Post writer quoted some of them in 1990:

“If he believes in creationism, he has established that he doesn’t have credibility to write about science,” said Robert Park, a physicist at the University of Maryland and head of the Washington office of the American Physical Society. “Creationism can be judged on scientific grounds and this guy has judged wrong.”

Others queried on the subject said that Mims’s belief in creationism indicated crippling flaws in his thinking, no matter what subject he might address. “We’re talking about a process here,” said Jon Franklin, a Pulitzer Prize-winning science writer now on the faculty of the University of Oregon. “If a person believes in ESP, then I have some questions about that person’s ability to think about psychology.”

Mims begs to differ. He says all his writings — he has written hundreds of articles and 70 books, he says — stand up to conventional rules of scientific evidence and reasoning, and should. His writing for the “Amateur Scientist,” a column on building gadgets and conducting home experiments, would have been no different, he said. “Let them judge my writings on their content and not on what I do on Sunday,” Mims said.

Charles Trueheart, “Big Bang over Belief at Scientific American,” Washington Post, November 1, 1990

The uproar did not prevent him from receiving the Rolex Award for Enterprise in 1993:

Mims simply went back to making many further contributions in lesser known venues though he documented the affair in detail at his website.

One of 50 “best brains in science”

In 2008, Discover Magazine named him “one of the 50 best brains in science,” a position to which the magazine stuck, despite angry clamor from Darwinists: “In our feature, we recognized Mims specifically for his contributions as an amateur scientist, and we stand by that assessment. His work on the Altair 8800 computer, on RadioShack’s home electronics kit, and on The Citizen Scientist newsletter has been undeniably influential.” The editors seem to have recognized that political correctness is not one of the branches of science.

In the Preface to his book, Mims tells a story that, perhaps, sums up his life of flashes of scientific creativity on the edges of the science establishment. He was working alone at Hawaii’s Mauna Loa Observatory, analyzing his ozone layer data, when he heard a car horn honking:

Moments later, a car door slammed shut, and a man began shouting and banging on the steel door of the building where I was working.

As the banging continued, I walked toward the door and heard the man shouting again and again, “Are any scientists in there?” Finally, I shouted back, “How can I help you?”

The banging stopped, and a friendly voice gently replied, “Are you a scientist?” When I slowly opened the door, a cherubic fellow with a short, gray beard smiled broadly and respectfully asked, “Are you a real scientist?”

Though I received a Rolex Award for my homemade instrument that measures the ozone layer, and published my discovery of an error in NASA’s ozone satellite data in Nature, the world’s leading scientific journal, I do not have a science degree. Yet no one had ever asked me whether I was a scientist, much less a real scientist. My life was an ongoing series of science adventures and projects, and I, too, had spent years banging on the doors of science, sometimes successfully. But I did not want to disappoint the visitor by telling him I was self-taught. Those thoughts spun through my mind before I offered a four-word reply that would need a book to explain. This is that book.

And the book is available here at Maker Shed or at Amazon on April 9, 2024.