Science Is Discovering That Mystical Experiences Are Real

When we contemplate, says neurologist Andrew Newberg, who studies such experiences, the frontal and parietal lobes of our brains quiet downIn podcast #165 at Mind Matters News (December 16, 2021), neurosurgeon Michael Egnor continued a discussion with neurologist Andrew Newberg on what we know about spirituality and the brain.

Dr. Newberg has published a number of books on the topic, including How God Changes Your Brain (2009) and Why God Won’t Go Away (2008). The “science is atheism!” clubhouse would not be very happy with him.

A partial transcript follows, with notes and links.

Michael Egnor: Do you see differences in the brains of people who are meditating in a theistic and a non-theistic way? Is there something different about belief in God that you can see in the brain?

Andrew Newberg: Well, that’s a great question. We haven’t specifically been able to make that kind of a differentiation in the sense of someone who believes in God and praying to God, versus just praying or just thinking about or just meditating. But part of the problem, I think… one of the things I get very excited about as a researcher are some of the methodological challenges of doing this kind of research. And so part of the problem is, is that if you are meditating on God, or praying to God, there’s something that you’re doing. You’re praying, you’re directing your mind towards something. Which may be very different from somebody who is directing their mind towards nothing. So one of the questions would be, well, what would be the right comparison, and how would we look at that?

There was one very interesting study that looked for example… and this may be a partial way of answering your question… that looked at people doing conversational prayer. And they found that when people were engaged in conversational prayer, talking to God, basically, that they activated a lot of the same language areas as they did having just a normal conversation with another person. And I think that there is an important point there, which is that… each of us has one brain. So as far as we know in the moment, it’s not that we have a different part of our brain that turns on or becomes active when we engage our religious and spiritual selves.

But if we pray to God, if we use our language, then our language centers of the brain will turn on. If we feel the love of God, well, our amygdala or our limbic structures will turn on. If we feel connected to God, then the areas that help us with our spatial representation of ourself help us to feel connect… that’s part of how that process goes. So in some sense, I always like to say that there isn’t one part of the brain that is your religious and spiritual part, it’s really your entire brain, because there are so many rich and complex ways in which we engage religious beliefs. And it can be cognitive, emotional, experiential, behavioral, and so forth.

So in many ways, to me it makes sense that we were given a brain that allows us to be able to have all of these different kinds of experiences, and that there isn’t just this extra part of ourselves that turns on when we walk into a church, for example, and begin to pray. But that being said, it will be interesting to see future studies, to see how much we can really differentiate different kinds of practices and those that are more theistic.

And of course, it’d be really interesting also to see, is there a difference between a Muslim, a Jew, and a Christian all praying to God. Are they all doing it in a similar kind of context? How much do the beliefs that go along with their tradition affect the way they think about their relationship with God? If a Muslim has the concept of surrendering to God, and a Christian may have a sense of connecting with God or being forgiven by God, then in and of itself, those could be differences. But not necessarily because of the actual perception of God, it’s just how they, themselves… the actual being of God, of course. But it’s how they’re perceiving that relationship.

So it’s a great question because it’s a very complex… we have to go through a very complex set of ways of thinking about that question and how we might best answer it. And then keep pushing our ability to keep thinking about those questions.

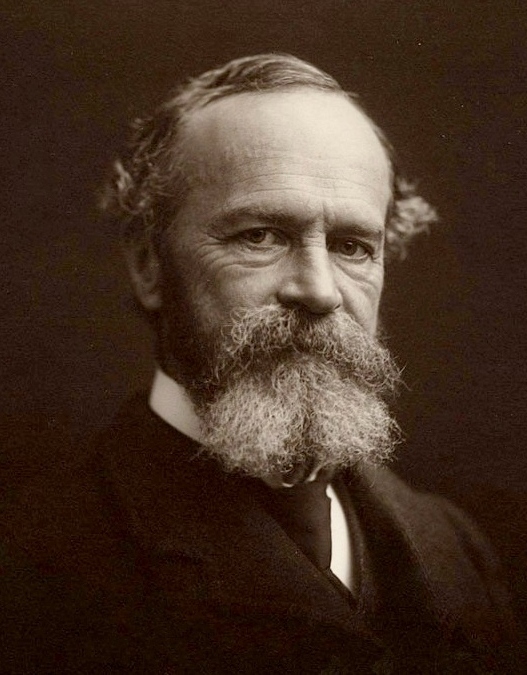

Michael Egnor: There’s a philosophical perspective on the mind/brain relationship that goes back into the 19th century. William James commented on it quite a bit: It’s not the case that the brain generates the mind, but rather that the brain focuses the mind. That is that the mind, as part of the soul, is a much larger thing than we ordinarily experience, and the brain is a biological organ that puts the mind to work in the natural world. But that the mind is something fundamentally different from the brain.

Note: William James (1842–1910) “was an original thinker in and between the disciplines of physiology, psychology and philosophy. His twelve-hundred page masterwork, The Principles of Psychology (1890), is a rich blend of physiology, psychology, philosophy, and personal reflection that has given us such ideas as “the stream of thought” and the baby’s impression of the world “as one great blooming, buzzing confusion” (PP 462). It contains seeds of pragmatism and phenomenology, and influenced generations of thinkers in Europe and America, including Edmund Husserl, Bertrand Russell, John Dewey, and Ludwig Wittgenstein” – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Michael Egnor: And I’ve always been impressed that great mystics… in the Christian tradition speak of a dark night of the soul. The necessity to, in some sense, suppress your brain activity or suppress your ordinary mental activities to allow oneself to connect to God and to connect to transcendent things. Do you see any evidence for that in the brain imaging?

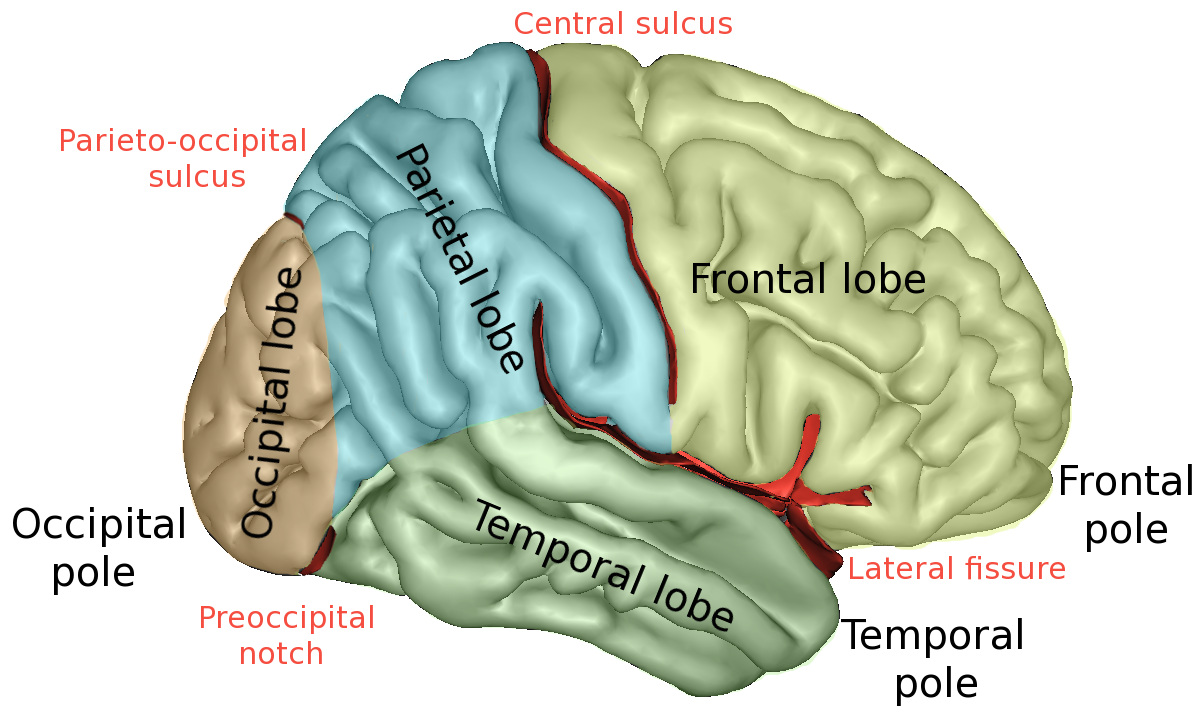

Andrew Newberg: Well, in some senses, yes. Again, we have to be careful about what we might conclude. But what has been fascinating to me is that in a number of the practices that we have studied, where people do feel as if they have released themselves or let go or surrendered to God in some way… there have been a number of our brain scan studies that have looked at this. One of the areas in our brain that actually particularly shuts down is the frontal lobe. And our frontal lobes are typically involved in helping us to do purposeful things and to… think about what we’re doing and do purposeful behaviors.

So it’s intriguing to me that this area of the brain starts to shut down when people have those very intense kinds of mystical experiences. These intense spiritual experiences where they do feel like they’re not in charge anymore. They are allowing it to happen and going along for the ride, if you will.

Michael Egnor:That’s absolutely fascinating. Because that’s exactly what the practical, everyday experience of people who do contemplation or various mystical prayer try to achieve. Is to basically shut down their own mind to connect more readily to God’s.

Andrew Newberg: Yeah, exactly. And so, yeah. I mean, there is some evidence for that. And of course, the other area of our brain which we have observed quieting down is the parietal lobe, which normally helps us to generate… take sensory information and generate our sense of self. Our spatial representation of ourself. And during these practices, that parietal lobe starts to quiet down, we think also in a similar kind of context, to blur that boundary between self and other. To kind of quiet down the ego self, if you will, in conjunction with the frontal lobe. And thereby helping to facilitate that kind of experience.

Next: Our beliefs can change our brains but the central core is what matters

Here’s an account of the earlier episode: Meet a doctor who thinks spirituality isn’t just all in your head. Can science study what you are doing when you pray? Andrew Newberg does and he says the effects are real. New neuroscience techniques can demonstrate that the effects are real, according to Andrew Newberg’s studies