Some People Think and Speak with Only Half a Brain

A new study sheds light on how they do itA study of six adults who each had half of their brain removed or partially removed as children is helping us understand how they retain language and thinking skills. This radical surgery (hemispherectomy) is done when epileptic seizures have severely damaged one lobe of the brain. Sensory, motor, or language deficits sometimes follow but many patients retain normal functions with only half a brain.

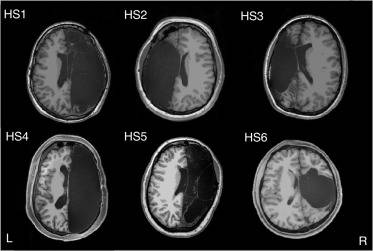

For each person in the study, the blood flow in seven brain regions was assessed and matched with that of six healthy volunteers, also checked against the fMRI data of 1,482 people.

While the six participants rested in an MRI scanner, researchers measured blood flow in seven brain regions that handle jobs such as vision, attention and movement. In the experiment, blood flow served as a proxy for brain activity. When activity in one part of the brain changes in lockstep with activity in another, that implies that the regions are working together and sharing information. These are signs of strong connections, which are thought to be crucial for a healthy brain.

Laura Sanders, “Some people with half a brain have extra strong neural connections” at ScienceNews

In fact, as the open-access paper reports, the six people with up to half their brain removed (see Figure 1 from the paper, right) had stronger connections than the six with whole brains.

One factor may be that, in the study group, the undamaged hemisphere had already been doing most of the work anyway before the surgery:

“The other hemisphere is already having to handle extra responsibilities before patients get treated,” Lynn Paul, a neuroscientist at Caltech and a coauthor of the study, tells The New York Times. “It continues to do so when you take out the damaged hemisphere.”

Kerry Grens, “Missing Brain Hemisphere Tied to Fortified Neural Networks” at The Scientist

Epilepsy often figures in controversies about whether the mind is simply a product of the brain or something more than that. Some highlights:

● The pioneer of the study of split-brain patients, Nobelist Roger Sperry (1913–1994) observed that

The neuroscientist Roger Sperry studied scores of split-brain patients. He found, surprisingly, that in ordinary life the patients showed little effect. Each patient was still one person. The intellect and will – the capacity to have abstract thought and to choose—remained unified. Only by meticulous testing could Sperry find any differences: their perceptions were altered by the surgery. Sensations – elicited by touch or vision – could be presented to one hemisphere of the brain, and not be experienced in the other hemisphere. Speech production is associated with the left hemisphere of the brain; patients could not name an object presented to the right hemisphere (via the left visual field). Yet they could point to the object with their left hand (which is controlled by the right hemisphere). The most remarkable result of Sperry’s Nobel Prize-winning work was that the person’s intellect and will – what we might call the soul– remained undivided.

Michael Egnor, “Science and the Soul” at The Plough

As neurosurgeon Michael Egnor notes, “The brain can be cut in half, but the intellect and will cannot.” That in itself implies that mind and brain are not the same thing.

Some split-brain patients experience automatic behavior of limbs, for example the famous alien hand syndrome. One woman, for example, would button her shirt with her right hand and find that her left hand was following along, unbuttoning it. Does that mean that she really does not have an intellect or free will, that it is all controlled by physical forces of which she is unconscious? Egnor thinks not:

All of the examples of alien hand syndrome involve particular acts—a hand unbuttoning a button or reaching for an object, and the like. This splitting of volition to do particular acts is splitting of the appetite, not splitting of the will. There are no examples of splitting of the will— no examples of simultaneous distinct abstract intentions.

Michael Egnor, “Does “alien hand syndrome” show that we don’t really have free will?” at Mind Matters News

In this case, the woman really did want to button up her shirt but her left hand seems to have been getting jumbled signals.

● Pioneer neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield noted that there are no “intellectual” seizures:

… epileptic seizures never evoke abstract intellectual thought—despite the materialist claim that abstract thought arises entirely from brain function. This inconsistency of materialist theory with scientific evidence was first noted by Dr. Wilder Penfield, who was the pioneer in epilepsy neurosurgery. Penfield noted that during his fifty years of clinical practice and research that stimulation of the brain—either by seizures or by a neurosurgeon during surgery—never evokes abstract thinking. I have noted the same thing in my practice. I know of no report in medical history of an abstract thought evoked by a seizure or by brain stimulation. Which is odd, if the brain causes abstract thought.

Michael Egnor, “Can Materialism Explain Abstract Thought? Part II” at Mind Matters News

Egnor notes that a range of neuroscience research findings is more readily explained by assuming that some aspects of thought–– abstract intellectual thought and free will–– are immaterial. That view certainly makes more sense of the surprising results from research into epilepsy.

Further reading:

Does brain stimulation research challenge free will? If we can be forced to want something, is the will still free? (Michael Egnor)

and

A short argument against the materialist account of the mind (Jay Richards)