Does brain stimulation research challenge free will?

If we can be forced to want something, is the will still free?If an electrode is applied to a specific brain region during “awake” neurosurgery, the patient may experience a strong desire to perform a related action and may even be mistaken about whether he has done so. For example, the study Movement intention after parietal cortex stimulation in humans (Karen Reilly et al, 2009), cited over 100 times at Pub Med, reported on patients undergoing awake brain surgery:

Parietal and premotor cortex regions are serious contenders for bringing motor intentions and motor responses into awareness. We used electrical stimulation in seven patients undergoing awake brain surgery. Stimulating the right inferior parietal regions triggered a strong intention and desire to move the contralateral hand, arm, or foot, whereas stimulating the left inferior parietal region provoked the intention to move the lips and to talk. When stimulation intensity was increased in parietal areas, participants believed they had really performed these movements, although no electromyographic activity was detected. Stimulation of the premotor region triggered overt mouth and contralateral limb movements. Yet, patients firmly denied that they had moved. Conscious intention and motor awareness thus arise from increased parietal activity before movement execution.

Reilly’s work appears to demonstrate that a sense of agency — and free will — can be elicited by direct brain stimulation. It implies that free will is probably an illusion. Materialists frequently cite this and similar research as evidence that the experiential illusion of free will is created by natural activities within the brain:

The important insight here is that the consciously experienced feelings of intention and agency are no different, in principle, from any other consciously experienced sensations, such as the briny taste of chicken soup or the red color of a Ferrari. Christof Koch, “The Will to Power—Is “Free Will” All in Your Head?” at Scientific American (2009)

The pioneer of brain stimulation studies on conscious patients, neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield, disagreed. He found that while he could stimulate several different types of responses—sensations, movements of limbs, memories, etc.—he could not stimulate a sense of agency. Patients still knew whether a movement was done by them or to them. A sense of will — free will — was beyond evocation by brain stimulation. Penfield, who began his career as a materialist, finished it as a passionate dualist.

The materialist interpretation of Reilly’s work is a misunderstanding of what the research actually shows. However, a genuine understanding requires a bit of background on the nature of agency in human beings.

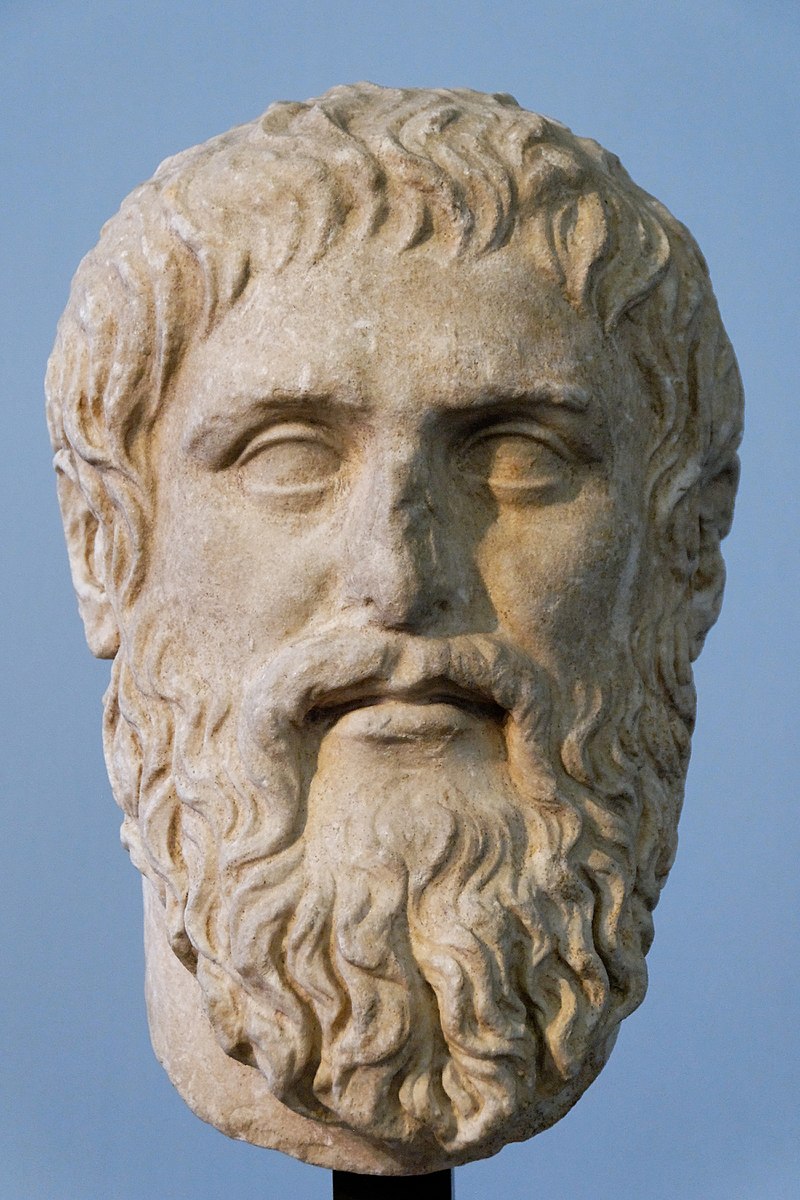

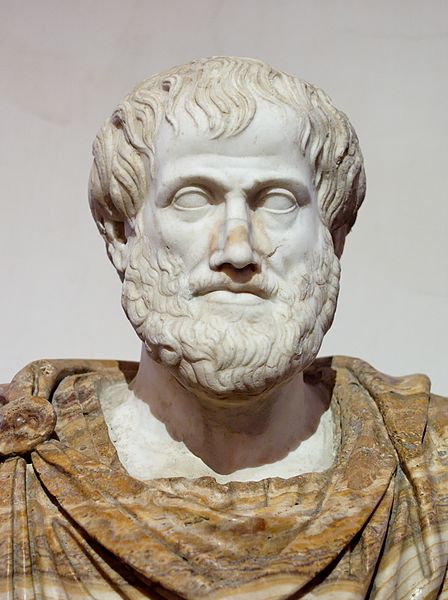

The classical understanding of the soul derived from Plato and Aristotle — which is, I think, correct — is that the immaterial aspect of the human soul consists of the intellect and the will. The intellect thinks abstract thoughts about universal things (mathematics, morality, etc.) and the will follows on the immaterial intellect. The will is naturally free in the sense that it is not determined by matter.

The material aspect of the soul consists of perception and passion. Perception and passion can be compared to intellect and will; they are its material “analogs.” The passions are also sometimes called the appetites. They are divided into six concupiscible passions (love, hatred, desire, aversion, joy, and sadness) and five irascible passions (hope, despair, fear, daring, and anger). These passions are material; they are caused directly by material processes in the brain. Thus, they are not freely chosen. We do not choose to feel anger or joy. We can, we hope, modulate our passions, but that does not make them free.

The immaterial aspects of the soul, as noted, are the intellect and the will. The intellect and the will are wholly immaterial aspects of the soul because they deal with immaterial objects (abstractions, logic, etc.) The intellect considers things as universals — concepts, abstractions, complex judgments, etc. The will carries out acts in accordance with the good as the intellect defines it.

The will and the passions interact with and modulate each other. The will constrains the passions. We may feel anger and be ready to strike out but our will (directed by our intellect) can prevent us from acting in a way that the intellect deems unwise. Sometimes our passions can override our will. A man may fall in love with a woman he knows is chronically unfaithful, despite his best judgment.

Keeping that in mind, let us look again at Reilly and her co-workers’ research. When they stimulate the parietal cortex, they are stimulating the brain regions that mediate the passions, which are material thoughts and intentions. Note that the stimulations always involved simple physical intentions and acts — moving a limb, etc. The stimulations did not evoke complex abstract intentions and acts — the patients didn’t reflexively decide to do integral calculus or donate to Amnesty International.

The researchers didn’t discuss whether the patients knew that their desires (passions) were stimulated or whether they were aware of their external origin. But even if they thought that their passions were their own, it would not be a violation of free will. Alteration of brain function can radically change passions (as any alcoholic knows). But the will, which is free and immaterial, remains, even if it is overwhelmed by the material passions. Sometimes, of course, the passions win and sometimes the will wins. But the will is spiritual and is free, and the passions are material and are not freely chosen.

Plato offers the best analogy to the relationship between the intellect, the will, and the passions: a chariot drawn by two horses with a human driver. The driver is the intellect and the horses are the concupiscible passions and the irascible passions. The reins are the will. The driver freely chooses where to drive the chariot, using the reins (the free will) to control the horses (the passions). Sometimes the horses are too strong; they take the bit in their mouths and pull the chariot where the driver doesn’t want to go. The chariot works best when the driver (intellect) uses the reins (free will) to guide the horses (passions) where the intellect does want to go.

Penfield’s studies found that no stimulation of any sort could erase the patient’s awareness that the feeling or act was externally caused, even if the patient experienced the feeling in a very personal way. “You caused me to think/do that” was the invariable explanation they gave him during the surgery. It was in that sense that Penfield says that he could not evoke agency.

Penfield’s studies found that no stimulation of any sort could erase the patient’s awareness that the feeling or act was externally caused, even if the patient experienced the feeling in a very personal way. “You caused me to think/do that” was the invariable explanation they gave him during the surgery. It was in that sense that Penfield says that he could not evoke agency.

Reilly and co-workers, as noted earlier, don’t address Penfield’s observations in their paper. But in my experience as a neurosurgeon, as in Penfield’s, patients always know that an evoked response was done to them and not by them.

In the debate about free will, we must understand that will is not, by itself, the same thing as agency (the ability to act). The will and passions work simultaneously, whether for our good or not, but the will and the passions are very different aspects of the mind. The will is spiritual and free. The passions are material and not free. They are caused by material processes in the brain and can be evoked surgically. They can, of course also can be evoked in many other ways, some of which are material substances (e.g. drugs, alcohol).

Will, as an immaterial power of the soul, competes with the passions for the control of our “chariot,” as Plato would say. But as we saw, will follows on the immaterial intellect as the means (the reins) by which we apply reason to our actions. In this sense, will is not determined by the material passions. It influences them and is in turn influenced by them. But because will is not determined by matter, it remains free.

Plato’s analogy of the chariot remains a compelling metaphor for human agency. We are influenced by our passions but free will is just as real and is fully consistent with modern neuroscience.

Michael Egnor is a neurosurgeon, professor of Neurological Surgery and Pediatrics and Director of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Neurological Surgery, Stonybrook School of Medicine

Michael Egnor is a neurosurgeon, professor of Neurological Surgery and Pediatrics and Director of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Neurological Surgery, Stonybrook School of Medicine

Also by Michael Egnor: Is free will a dangerous myth?

Does your brain construct your conscious reality? Part I A reply to computational neuroscientist Anil Seth’s recent TED talk

Does your brain construct your conscious reality? Part II In a word, no. Your brain doesn’t “think”; YOU think, using your brain