How Ancient Philosophers Can Help Design Better Computers

The Kubernetes program, for example, steers groups of computers the way, in the ancient image, a navigator steers a shipAs you browse the internet today, you are using a powerful, invisible piece of technology called Kubernetes.

Kubernetes is a system that governs how many computers work together to create the websites we all love to visit.

When you visit a website, it may not seem very complicated, but beneath the surface is a very sophisticated interconnected group of computer programs that make sure not only you, but millions of people around the world can see the very same website, the very same way, in a split second. No simple feat!

The name “Kubernetes” comes from the ancient Greek word for a ship’s navigator, it’s “governor,” if you like. Like a navigator directing a ship, Kubernetes directs computers over the rough sea of the internet.

More than just a surface similarity

The connection between the internet and the sea can be explored in depth.

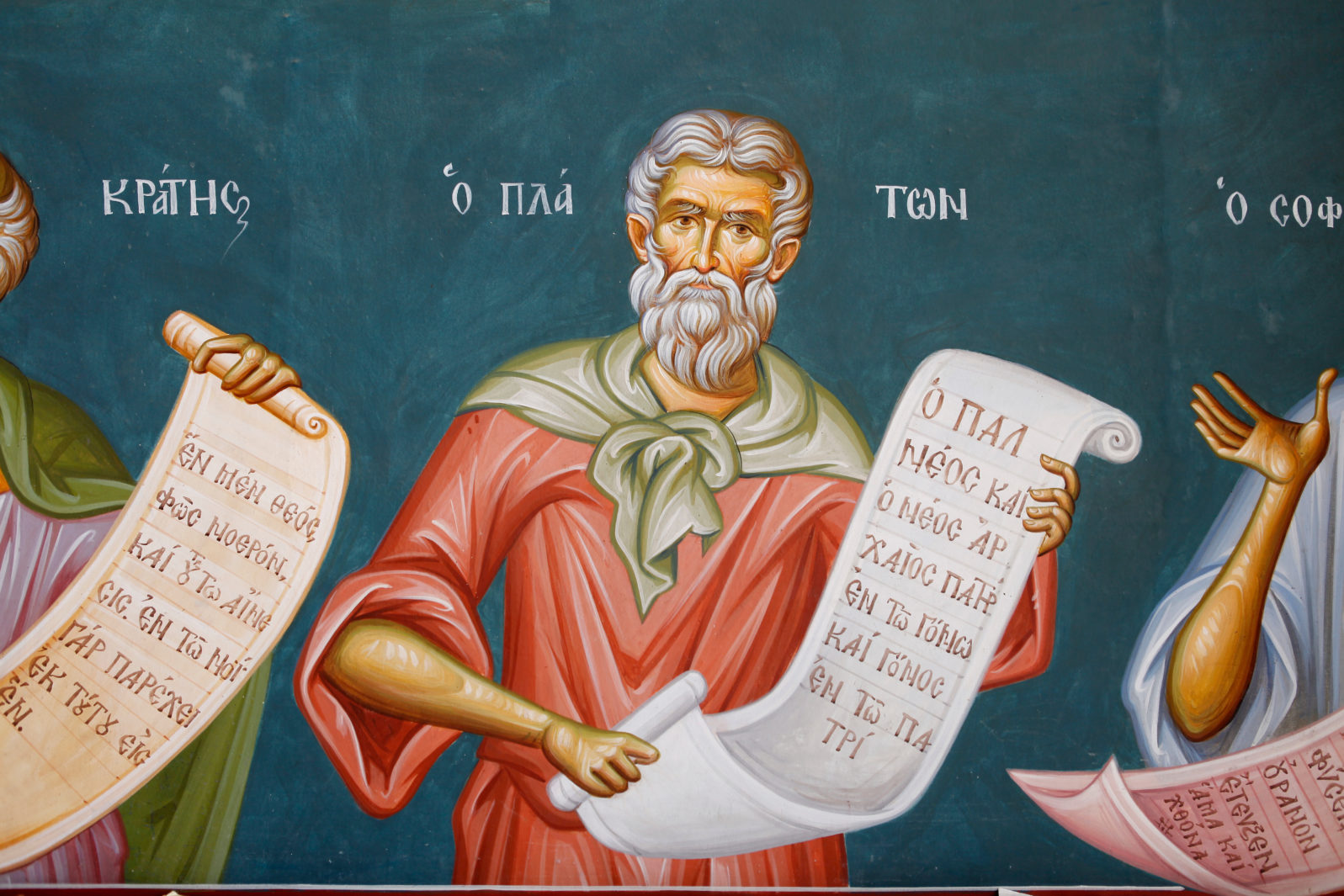

The two ideas of navigator and governor come together in a story in the philosopher Plato’s Republic. There, Plato’s teacher Socrates is presented as telling a story about a ship whose crew competes to to take over and loot the cargo instead of sailing it. Because the navigator is trying to tell them where the ship should be going, which won’t help them loot, the sailors consider the navigator a loony. Socrates likens the bedraggled ship to a city that scorns its philosophers as useless.

How does this relate to the internet and computers? Things will become clearer as we come to understand what Socrates means by a philosopher.

Socrates’ philosopher is not an ivory tower academic churning out salami-slice papers to bring in grants. A philosopher is someone who loves wisdom, who loves, in particular, something Socrates calls the form of the good. The form of the good is the most real thing there is; while everything else is but a copy of the good. Thus Socrates thinks a philosopher makes the best governor or navigator for society because the philosopher understands the way things should be. As the great Yogi Berra once said, “If you don’t know where you’re going, you’ll end up somewhere else.”

What Kubernetes does is different

Coming back to Kubernetes, the connection becomes clear when we see how it functions, and what makes it different from computer systems we are more used to, like Microsoft Windows.

An operating system like Microft Windows has one basic task. It is given some computer code, which it runs, no questions asked. If there is an error in the code, Windows doesn’t “know” about it. It will keep going down the code path until it crashes in the blue screen of death. It might throw out cries of alarm on the way to destruction, but doesn’t know how to correct the course.

Kubernetes, on the other hand, works a little differently. It can be thought of as something like a ship or society. Instead of a single system doing one thing, it is a composite of different autonomous agents, called controllers, who are working together to bring about a shared plan. This plan is described by a document called a manifest, similar to a ship’s manifest. The manifest describes what kinds of things should exist within the computer system governed by Kubernetes. The agents each have their own role in making the manifest a reality.

The basic unit of work on the Kubernetes ship is known as a pod, similar to a cargo container. A program known as the scheduler works with the controllers to make sure all the pods exist as required by the manifest. If something goes wrong with a pod, then the scheduler and controllers correct the problem. This makes Kubernetes as a whole much more resilient than a system like Windows.

We can take a step back and think of Kubernetes as a circular motion, where the controllers and scheduler are constantly comparing the way things are to the way things should be, and making constant corrections to make the state of reality match the manifest.

Kubernetes’ circular motion is very similar to one aspect of how our minds work.

When we have an intent we plan to carry out, our minds are constantly comparing the way things should be, i.e. our intent, to the state of the environment around us. They work together with our body make the environment match our intent. This is why ancient philosophers like Plato (c. 427 – 348 BC), Aristotle (384– 322 BC), and Marcus Aurelius (121–180 CE) considered intelligence to be a kind of circular motion that brings order out of disorder. As disorder is the opposite of information, it is the circular motion of intelligence that helps create information in the world around us.

And so we see that by drawing on the insights of ancient philosophy, we can design a computer system that takes a better path than flying headlong into destruction when something goes wrong.

Note: For those interested in learning more about Plato’s theory of the soul check out Towards a Unified Platonic Psychology by John Mark Reynolds.