What If We Lost the Power to Think Abstractly?

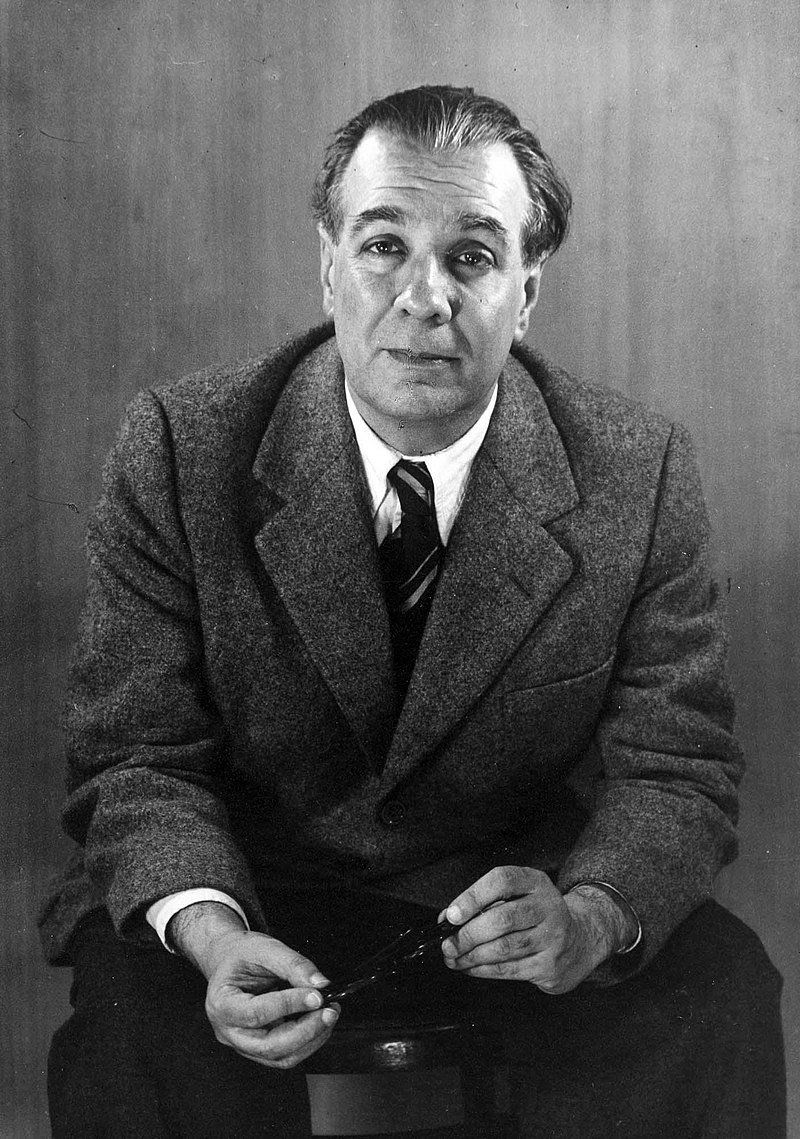

Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges depicts a character whose total recall prevents him from using abstractions, though he recognizes their existenceIt’s commonplace to hear that humans differ from most life forms in that we have the power to abstract — to deal with concepts like “one trillion” or “representative democracy.” But what would happen to that power if we had a human intellect and the power of total recall? Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges (1899–1986) wrote a story about that. As humanities professor William Egginton explains at Aeon, Borges framed his thoughts as a series of stories (Artifices 1944). They concern a man, Ireneo Funes, who acquires total recall after an accident that otherwise leaves him paralyzed. Some of the effects — as interpreted by the story’s narrator — are not quite what we might anticipate:

Public Domain

[Funes] was able to reconstruct every dream, every daydream he had ever had. Two or three times he had reconstructed an entire day; he had never once erred or faltered, but each reconstruction had itself taken an entire day. –

from Collected Fictions (1998) by Jorge Luis Borges, translated by Andrew Hurley; William Egginton, Quantum poetics, Aeon, 14 September 2023

Significantly, total recall also means that Funes loses the power of abstraction. He can process numbers only as individuals:

Instead of seven thousand thirteen (7013), he would say, for instance, ‘Máximo Pérez’; instead of seven thousand fourteen (7014), ‘the railroad’; other numbers were ‘Luis Melián Lafinur,’ ‘Olimar,’ ‘sulfur,’ ‘clubs,’ ‘the whale,’ ‘gas,’ ‘a stewpot,’ ‘Napoleon,’ ‘Agustín de Vedia.’ Instead of five hundred (500), he said ‘nine.’

Collected Fictions (1998)

Egginton observes,

Aside from being hilarious, the idea of Funes using one numeral to designate another captures the enormous disability that his superpower entails. Borges’s narrator notes this as well, pointing out that he tried to impress upon Funes that his system entirely misses the point of numbers, but to no avail. Funes isn’t capable of generalisation, of taking one sign as a stand-in for more than one thing. He lives in a world entirely populated by individuals, and requires a representative system that honours that individuality.

Egginton, Quantum poetics

In short, “Funes is incapable of the basic function underlying and enabling all thinking – abstraction.”

Not only was it difficult for him to see that the generic symbol ‘dog’ took in all the dissimilar individuals of all shapes and sizes, it irritated him that the ‘dog’ of three-fourteen in the afternoon, seen in profile, should be indicated by the same noun as the dog of three-fifteen, seen frontally. His own face in the mirror, his own hands, surprised him every time he saw them.

Collected Fictions (1998)

The central paradox of human language

But Egginton, author of The Rigor of Angels: Borges, Heisenberg, Kant, and the Ultimate Nature of Reality (Penguin Random House, 2023), points out a paradox about Fuentes position: He is frustrated by other human beings’ use of language but “It is — and this is the whole point of Borges’s reflection — utterly impossible to be as immersed in the present as Funes claims to be and also to be aware enough of the generality of language to criticise it.” In other words, how does Fuentes even know that there is a problem? Dogs, for example, can’t generalize (abstract) either but, as a result, they don’t even try. They simply listen for words they can associate with something concrete (Down! Walk! Dinner!)

Curiously, Egginton goes on to say, German physicist and philosopher Werner Heisenberg (1901–1976) was also writing about language in 1942, though his thoughts were not published until much later. He argues that Borges and Heisenberg “converged on the notion that language both enables and interferes with our grasp of reality.”

Heisenberg is far better known, of course, for his Uncertainty Principle, that we cannot know both the speed and the position of a particle with complete accuracy. But he believed that language shared in that creative uncertainty:

For Heisenberg, science translates reality into thought. Humans, in turn, require language in order to think. Language, however, depends on the same limitations that Heisenberg’s work from the 1920s showed held for our knowledge of nature. Language can home in on the world to a highly objective degree, where it becomes well defined and useful for scientists who study the natural world. But, when it is so focused and finely honed, language loses its other essential aspect, one we need in order to be able to think. Specifically, our words lose their ability to have meanings that change depending on their context.

Egginton, Quantum poetics

Perhaps we might say that Fuentes’s problem is that, to the extent that he understands the exact position of everything, he understands the speed of nothing. All human knowledge is partial; making choices about where to focus gives us the hope of knowing at least something.

Note: There is such a thing as total recall, for which the technical term is highly superior autobiographical memory (HSAM), but it is not nearly as vivid or comprehensive as Fuentes’ fictional experience. See: Ever Wish You Had Total Recall? Ask People Who Do… Recall of every detail of one’s past works out better for some people than for others. Just why some people can recall almost everything that happened to them is a mystery in neuroscience, in part because they are few in number.