The Likely Reason the Human Mind Has No History

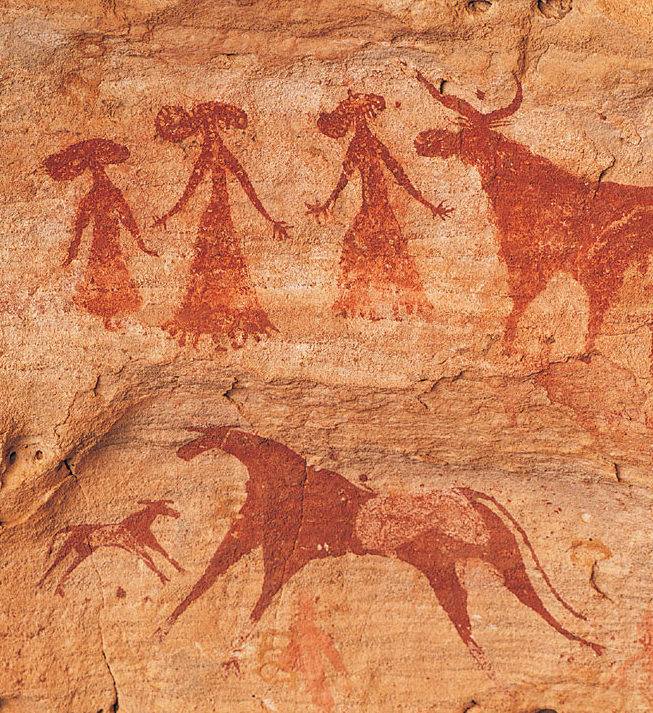

Our efforts to explain the origin of the human mind fall flat because we are looking for an origin that probably doesn’t existRecently, there was a bit of discussion around my contention that the human mind has no history. We suddenly discover the minds of long-deceased peoples, perhaps in cave art that pushes back the timelines we laboriously constructed.

Mental capacity is not the same thing as technical competence. Technical competence is far too heavily skewed in favor of people who arrived later to be a grading system for mental capacity. For example, before mining and metallurgy, we could imagine many things we couldn’t do. The brains behind the James Webb Space Telescope are not necessarily smarter than the first philosopher of science Aristotle (384– 322 BC). But they have tools for acquiring knowledge that he didn’t. So they know many things he could only reason about.

So how did the human mind evolve?

At Wikipedia, we are told, “Many traits of human intelligence, such as empathy, theory of mind, mourning, ritual, and the use of symbols and tools, are somewhat apparent in great apes, although they are in much less sophisticated forms than what is found in humans like the great ape language.” (27 November 2023)

That is misleading, of course. Great apes — but also crows, elephants, and octopuses — show many qualities we recognize as forms of intelligence. Some researchers spend their careers on efforts to place one or another of them on a continuum with human intelligence, to show that we are “not special” as they so often put it. The roadblock is that what separates our intelligence from theirs is not a physical quality.

That said, of the making of many books there is no end, so a number of recent ones have defended theories about how the human mind or human consciousness evolved. Here are three:

Living in large groups. In a 2014 entry, Thinking Big: How the Evolution of Social Life Shaped the Human Mind (Thames & Hudson 2014) evolutionary psychologists Clive Gamble, John Gowlett, and Robin Dunbar argue that living in larger groups was the magic ingredient. From a review in Nature:

The authors show that there is a strong correlation between relative neocortex volume and mean social-group size in monkeys, apes and humans. They attribute this to the fact that the complexity of group interactions increases with group size. A large brain gives individuals the means to forge strong social ties that enhance their personal fitness and the group’s social cohesion; in particular, a large neocortex supports a “theory of mind”, whereby individuals can form mental representations of the beliefs and intentions of others. This enables them to enter into complex agreements and coalitions, and to track multiple social relationships through time and space.

Gintis, H. Sociobiology: The distributed brain. Nature 509, 284–285 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1038/509284a

Reviewer Gintis doesn’t really buy the idea; he favors hunting with lethal weapons: “… the presence of lethal weapons undermined our ape ancestors’ characteristic social-dominance hierarchy, which was based on the physical prowess of the alpha male. This created a leadership void that could be filled not by appeal to physical strength, but rather by social persuasiveness and then a subtle ability to form effective coalitions.”

A rare genetic mutation. Fast forward to 2021: In How the Mind Changed: A Human History of Our Evolving Brain (Little, Brown Spark 2021) neuroscientist and writer Joseph Jebelli argues that “A single mutation is all it takes.” As fellow neuroscientist (and medic) Raymond Tallis describes the thesis at Times Literary Supplement,

A rare genetic mutation shrinking the jaw permitted an expansion of the skull to house the enlarged brain. The use of fire to cook food reduced the burden of chewing and effectively “allowed humans to build an external stomach in which fire, rather than digestive enzymes, was used to break down food before it was processed by the body”. This enabled the maintenance of the calorie- hogging expanded brain of Homo habilis and its successors, notably Homo sapiens, who emerged 400,000 years ago. (December 23/30, 2022)

Tallis does not think that Jebelli makes good on his promise to show that a rare genetic mutation is all it takes.

Five breakthroughs. A 2023 entry by AI specialist Max Bennett argues that it took five breakthroughs. In A Brief History of Intelligence: Evolution, AI and the Five Breakthroughs that Made Our Brains (HarperCollins 2023).

From a review at ABC News by Rob Merrill:

Bennett’s premise — he’s a software entrepreneur who founded a company called Bluecore that “helped predict what consumers would buy before they knew what they wanted” — is that humans won’t ever create true artificial intelligence without understanding exactly what led to the real intelligence we already possess. So he begins with those nematodes — worms, to you and me — and painstakingly details the five breakthroughs that over the course of billions of years evolved into the three-pound brain that is folded into all of our skulls. (October 23, 2023)

Merrill offers no suggestion that Bennett sheds any light on the origin of the human mind before deflecting to the future of AI — doubtless the topic in which he has deeper grounding.

We can learn a lot of prehistory from books speculating about the origin of the human mind, just as we can learn a lot of biology from books speculating about the existence of extraterrestrial life. But no book can take us beyond speculation in either case, though for different reasons.

With ET, no amount of plausibility adds up to fact; only evidence will do. With the human mind, immaterial entities have no history. We either detect their material signatures or we don’t. For example, there is a history of civilizations discovering the Pythagorean theorem. But the theorem itself has no history. Neither does the mind that apprehends it.