The Hyper-Specialization of University Researchers

So many papers are published today in increasingly narrow specialties that, if there is still a big picture, hardly anyone can see itThe Bible warns that, “Of making many books there is no end; and much study is a weariness of the flesh.” Nowadays, the endless making of books is dwarfed by the relentless firehose of academic research papers. A 2010 study published in the British Medical Journal reported that the U.S. National Library of Medicine includes 113,976 papers on echocardiography — which would weary the flesh of any newly credentialed doctor specializing in echocardiography:

We assumed that he or she could read five papers an hour (one every 10 minutes, followed by a break of 10 minutes) for eight hours a day, five days a week, and 50 weeks a year; this gives a capacity of 10000 papers in one year. Reading all papers referring to echocardiography… would take 11 years and 124 days, by which time at least 82142 more papers would have been added, accounting for another eight years and 78 days. Before our recruit could catch up and start to read new manuscripts published the same day, he or she would — if still alive and even remotely interested — have read 408,049 papers and devoted (or served a sentence of) 40 years and 295 days. On the positive side, our recruit would finish just in time to retire.

That was 2010. The reading list is now longer, much longer.

The field of echocardiography is hardly unique. More than a hundred million academic research papers have been published with millions more published every year. This deluge is not just the unwelcome explosion of predatory journals that will publish anything for a fee, no questions asked. Consider the world’s leading engineering and science organizations. The Association of Computing Machinery now publishes 59 journals, while the American Chemical Society, Society of Mechanical Engineers, Physical Society, and Medical Association publish 39, 35, 15, and 13 respectively.The number of journals published by the IEEE exceeds 200 and the number published by Nature has reached 157 (up from just one 50 years ago).

An old academic aphorism is that, “Deans can’t read, but they can count.” Every hire, promotion, and grant application depends on a publication list. In addition to the multiplication of journals, publication counts are pumped up by hyper-authorship—papers with literally hundreds or even thousands of co-authors. Between 2014 and 2018 there were 1,315 papers published with more than 1,000 co-authors. A 2015 paper had 5,154 (it took 24 of the paper’s 33 pages to list the authors). A 2021 paper set the Guinness record with 15,025 co-authors, and celebrated on Twitter.

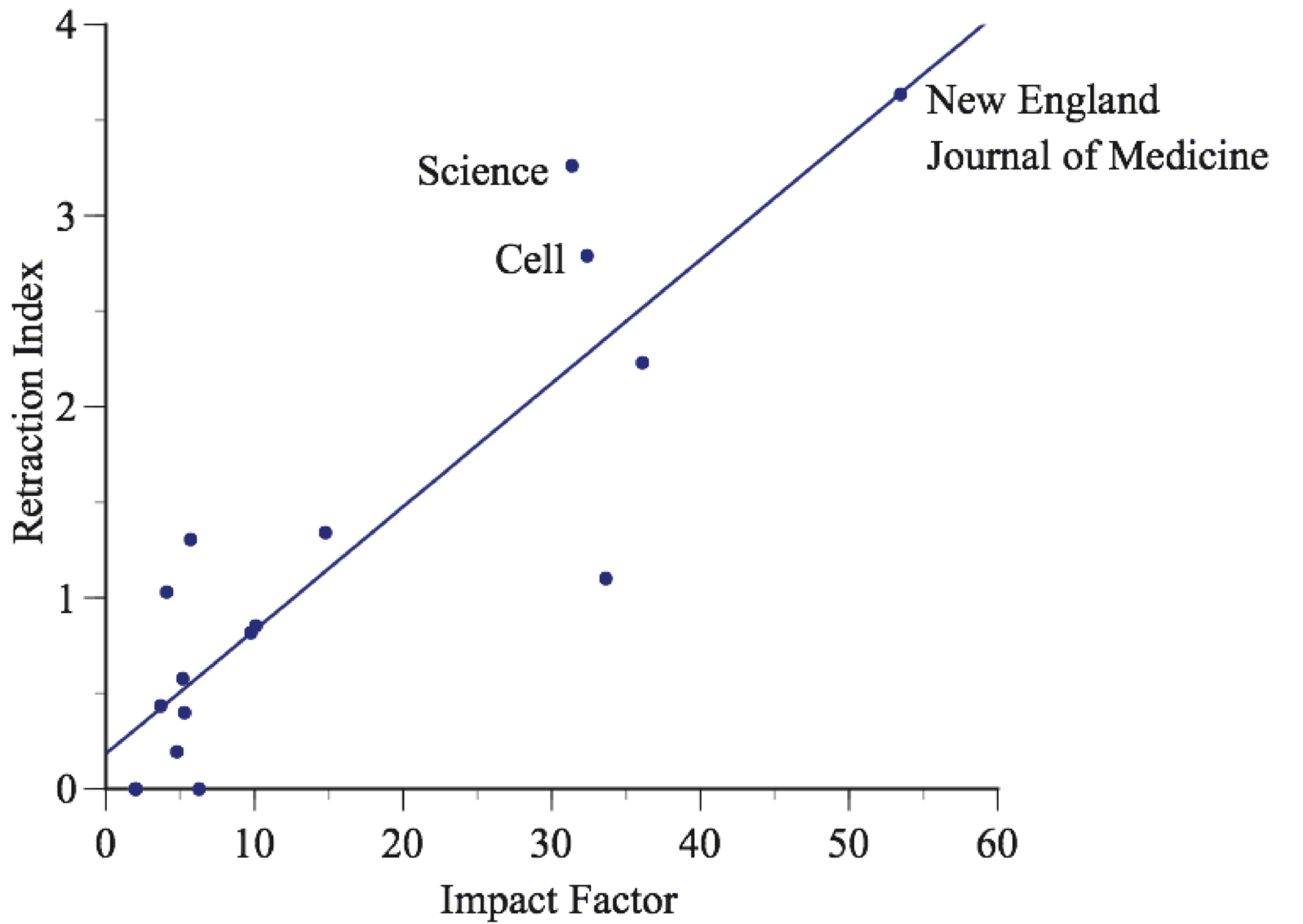

Peer review is no guarantee of quality There are far too many papers than could be reviewed carefully and most active researchers are far too busy publishing their own work to do more than cursory reviews of other people’s papers. Nor is journal reputation a guarantee of quality. If anything, it seems that papers published in high-impact journals are more likely to be retracted subsequently:

Keeping up with research in one’s own field is daunting. Keeping up with research in related fields is overwhelming. The theoretical physicist, J. Robert Oppenheimer, once wrote that, “The history of science is rich in example of the fruitfulness of bringing two sets of techniques, two sets of ideas, developed in separate contexts for the pursuit of new truth, into touch with one another.” Closer to our own fields, John Maynard Keynes (1883–1946) wrote that,

The master-economist must possess a rare combination of gifts. He must be mathematician, historian, statesman, philosopher — in some degree. He must understand symbols and speak in words…. He must study the present in the light of the past for the purposes of the future. No part of man’s nature or his institutions must lie entirely outside his regard.

Yet, too many researchers see the blurring of disciplinary boundaries as a threat to disciplines and too many universities penalize researchers who cross disciplinary borders by making it harder for them to get tenure and be promoted, with the highest performing multidisciplinary researchers penalized the most.

There is little disagreement that we need more multidisciplinary researchers, people who can integrate insights from multiple fields. Instead, researchers tend to work in isolated silos, barely aware of what other researchers are doing in other silos.

We have seen this repeatedly in data science, where some people think that data science is just about writing computer code to find patterns in large databases, and are blissfully unaware of the pitfalls of data mining. Others use thoroughly discredited procedures, like stepwise regression, principal components regression, and ridge regression, because they don’t know that these methods have been discredited. A few weeks ago, a young professor with a PhD from Harvard gave a talk at Gary’s college where he used all three of these discredited procedures!

Science will advance faster and more reliably if researchers peek outside their silos and read papers in other fields and talk to people in other fields.