How Video Games Helped Researchers Unpack Real History

Experts in ancient Egyptian life helped game developer Ubisoft create Origins in 2017 and Ubisoft wanted to return the favorThe massive mysteries of ancient Egypt were undecipherable until the discovery of the Rosetta Stone in 1799 because the meaning of the hieroglyphics in which the inscriptions were composed had been lost:

The Stone featured text engraved in Egyptian hieroglyphs alongside easily recognized Greek from the 2nd century BC. It enabled a first stab at interpreting the mysterious older symbols. But there are a lot of symbols and only one Stone. So it has been slow work for centuries.

A job for machine learning?

In 2017, with much help from Egyptologists, game creator Ubisoft’s Montreal division released Assassin’s Creed: Origins, a game set in Egypt during the reign of Cleopatra (70/60–30 BC). The goal was to create authenticity as well as excitement.

In return, Ubisoft started to work on the Hieroglyphics Initiative to see if machine learning could speed up the tedious translation process. Macquarie University Egyptologist Bree Kelly, who helped develop the program, offers some insights into why translating hieroglyphs is challenging:

Ancient Egyptians regularly used more than 700 hieroglyphs, wrote their texts in different directions, and eschewed vowels, punctuation, and space between words. Many early researchers incorrectly assumed hieroglyphs were purely symbols; in fact, they can represent objects, ideas, or sound groups.

Bree Kelly with Brian Ballsun-Stanton, Camilla Di Biase-Dyson, and Alexandra Woods, “Can Machine Learning Translate Ancient Egyptian Texts?” at Sapiens (June 9, 2022)

Jean-François Champollion’s detailed analysis of the Rosetta Stone in 1822 first “cracked the code” and the use of photography from the 1890s onward enabled many more workers to get involved in further translation. But it was still pretty slow work.

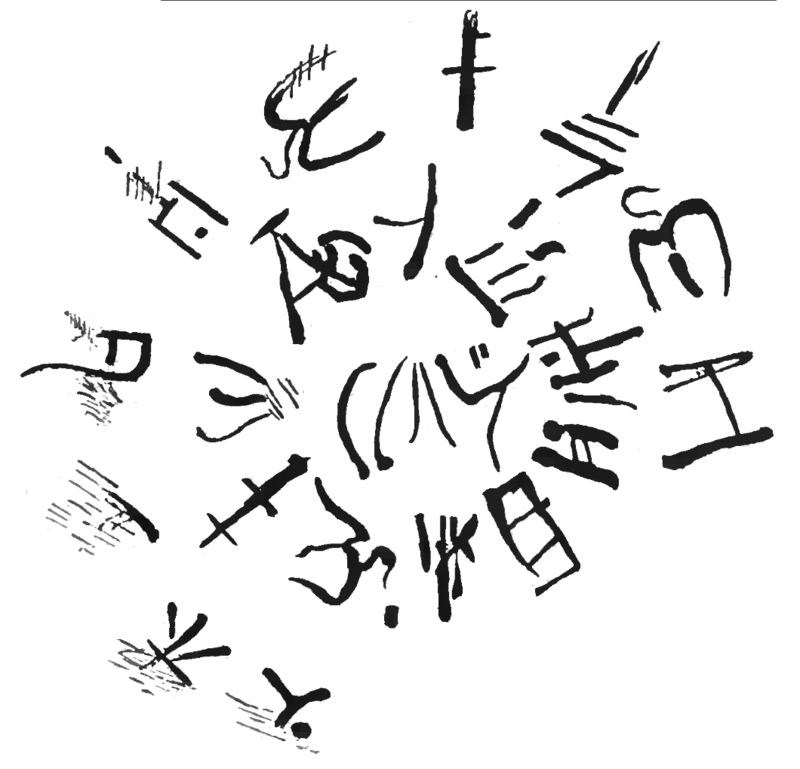

Google Arts and Culture,which had taken over the project, released the machine translation program, now called Fabricius, in 2020 in English and Arabic. Essentially, the program “cleans up” hieroglyphics and suggests possible translations:

Of course, it’s still not simple, Kelly notes. “[H]ieroglyphic signs can have multiple meanings, their spelling varies across thousands of years, and different scribes and artists had stylistic idiosyncrasies.” But those problems would all exist anyway; Fabricius, for which she created step-by-step instructions, speeds up the Egyptologist’s routine work.

Machine learning has its drawbacks

Recognition of symbols can be disappointingly low (27% accuracy from traced photos, for example). But, as Kelly notes, accuracy in language translation improves over time when more data sources are incorporated because they narrow the choices for the program. A bigger challenge will be getting Fabricius to work with whole sentences and “larger texts that incorporate grammar and syntax.”

Perhaps the most significant change is that the digitization of material for Fabricius enables more students to get involved with translation, enabling more analysis and perhaps increasing the chances of breakthroughs. Many more, at any rate, than could work on the Rosetta Stone or visit the tombs in person.

Meanwhile, some have fun using Fabricius for sending messages, perhaps somewhat like the use of emojis to express a concept:

Note: The featured photo is by Jeremy Bezanger on Unsplash.

Here are some other ways AI is opening up our ancient and early modern past — or shedding light on literary or artistic controversies — by assuming vast technical chores, thus rendering answers sooner and more affordably:

AI restores lost parts of Rembrandt’s Night Watch. The iconic painting’s edges were cut off to fit a certain space in a town hall in 1715 and the cut parts were never recovered. The AI restoration depended on computing from a small copy produced by a contemporary artist, Lundens, for clues, comparing Rembrandt’s style with his.

How a searchable database is helping decipher a lost language. (Minoan A)

Does AI challenge Biblical archeology? Sadly, many surviving documents are so damaged that they cannot be read using traditional methods. The more scrolls are deciphered using new AI methods, the more archeologists will have to study and write about.

How much can new AI tell us about ancient times? An ambitious new project hopes to use the predictive text that cell phones use to unlock their stories. Researchers face conundrums when using neural networks to figure out what people in the ancient past were thinking.

and

Can AI prove that Shakespeare had ghostwriters? An author’s unique style is like a fingerprint. AI can sometimes fill it in. Turning AI loose on some of these vexing problems should give literary scholars more to write about rather than less. The AI verdict may not always be right but it is bound to be food for thought.