Critical Lessons From the COVID Crisis — From a Leading Historian

Niall Ferguson sees the economic impact of the COVID shutdown as comparable to fighting World War II — or World War IIIEarlier this month, historian Niall Ferguson spoke to COSM 2021 about the real lessons from the strange year and a half of the COVID-19 pandemic.

A reader might be forgiven for wondering whether, in the cacophony of conflicting claims, opinions, and prophecies of doom, there are any useful lessons to be learned (other than: Turn off the TV).

Ferguson thinks there are indeed lessons — if we compare the recent pandemic and how it was handled with pandemics of the past. In his recent book, Doom: The politics of catastrophe (2021), he argues that “All disasters are in some sense man-made” and that — despite advances in science — we are getting worse, not better, at handling them:

Yet in 2020 the responses of many developed countries, including the United States, to a new virus from China were badly bungled. Why? Why did only a few Asian countries learn the right lessons from SARS and MERS? While populist leaders certainly performed poorly in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic, Niall Ferguson argues that more profound pathologies were at work–pathologies already visible in our responses to earlier disasters. — from the Publisher

His analysis is based on several key assumptions:

➤ The worst of the pandemic is behind us. Tuning out the frequent alarms in media about Greek alphabet variants (Delta, Kappa, Zeta, and such), the disease is becoming endemic. That is, if history is any guide, there will be multiple future waves in a population that is already learning coping strategies but it won’t be a crisis.

➤ It’s not clear how many people died prematurely due to COVID. Estimates range from 5 million through to 19.8 million worldwide. Ferguson told the gathering that the meaningful measure to focus on now is excess mortality. That includes “people who, who died for reasons that were not directly attributable to the SARS COV-2 virus but whose deaths were hastened by the conditions of the pandemic, people who couldn’t get to hospital to see the doctor about their heart condition, or couldn’t get their cancer treated early enough.” Excess mortality is declining.

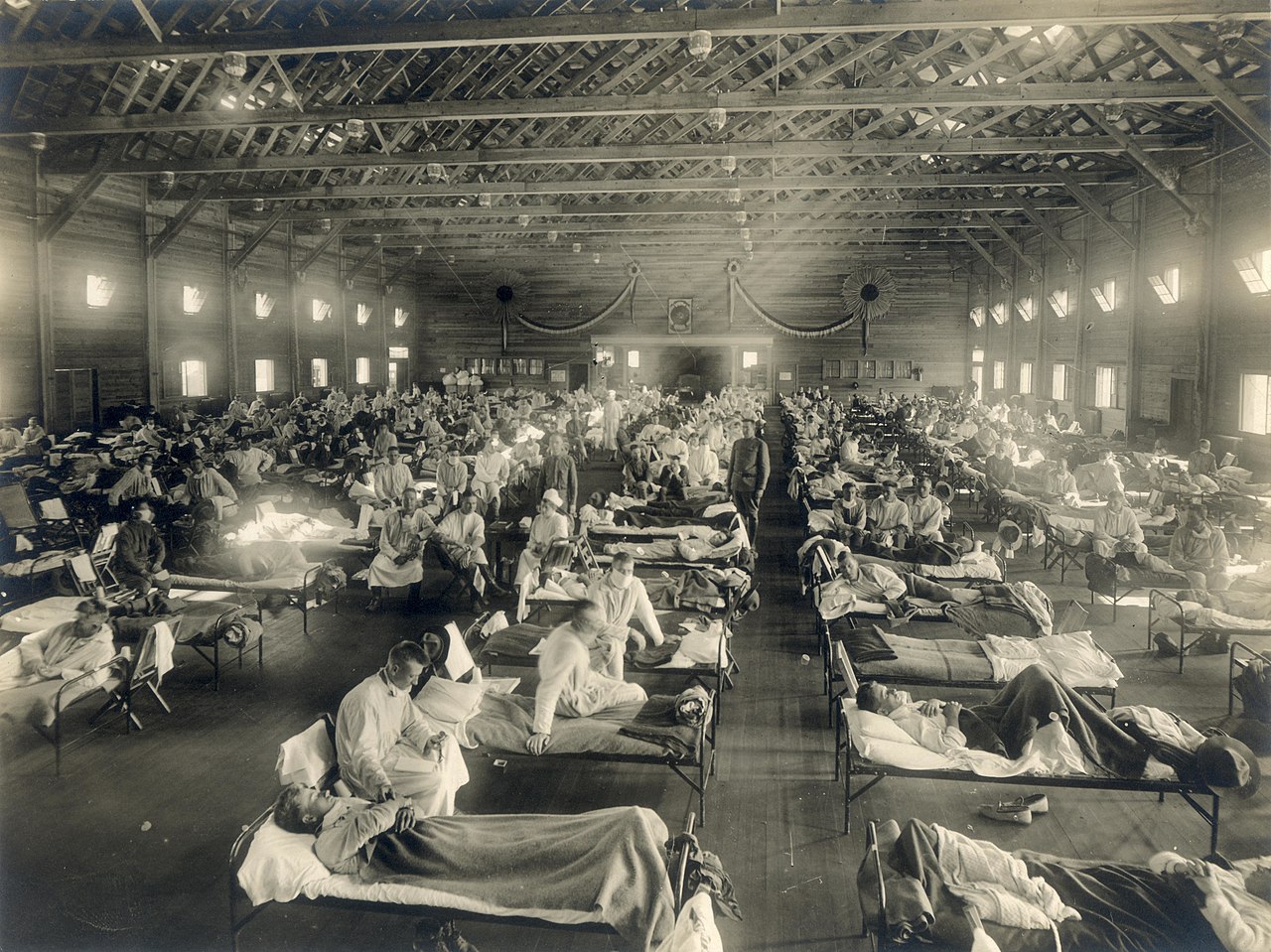

➤ Covid-19 is nowhere close in severity to the great pandemics of the past, not even of the recent past: “It’s nothing close to the Black Death or the Plague of Justinian, which we think may have killed as many as a third of humanity. We’re really talking here at this point of, of a death toll of 0.066% of the world’s population. If you buy the Economist’s highest estimate, 0.26%, that’s a trivial number by comparison with the Black Death. It’s an order of magnitude smaller than the death toll of the 1918–19 Spanish influenza. In fact, it was only this year that COVID-19 overtook the 1957–58 Asian flu in terms of its, mortality relative to global population.”

Pandemics you’ve never heard of

“And most people had never heard of the 1957–58 influenza pandemic because it was largely forgotten even by the people who lived through it. It doesn’t figure as a major event in our historical memory. We think of Sputnik. We don’t think of the Asian flu. The thing that this current pandemic is closest to is something that happened in 1889–90, which might possibly have been a coronavirus pandemic. Contemporaries called it the Russian flu.

“I’m almost certain, none of you had ever heard of that pandemic until I told you about it. No, because it’s not a major historical event. It’s not the kind of thing that makes it into the history books. “So that helps us sense that this [COVID-19] was not a really big pandemic by historical standards. It was up there with the 1889–90 Russian flu.”

To put it the statistics in perspective, Ferguson cited figures from Britain in 2020 that showed that mortality rates were similar to those of 1918 (Spanish flu), 1940 (Battle of Britain), and 1951.

1951? It was a bad winter for illness but, “it remarkable that a year characterized by excess mortality, as severe as we saw in Britain last year has almost entirely been forgotten.”

So, he asks, “Why then did this one feel so different? Why has it been so problematic? And for many people traumatic?”

And answers: “It’s not the death toll that makes COVID-19 a historically significant event. By that measure, it’s not a remarkable disaster. What makes it a remarkable disaster is the economic and the social and political fallout. Let me start with the economics.

COVID’s key effect was the economic devastation of lockdowns

Niall Ferguson sees the economic impact of the COVID shutdown as comparable to fighting World War II. Or World War III: “If all you knew about the United States of America was the debt to GDP ratio and the size of the fed balance sheet, you would assume that World War III had broken out, perhaps in 2008 or 2009, and was still raging with no end in sight. Only in World War II has the U S federal debt in public hands relative to gross domestic product rocketed as steeply as it did in the years after the global financial crisis [of 2008].”

The reason the economic impact was so severe this time around, he noted, is that in 1918 and 1957, the government did not have the option of locking people down to their homes because in 1957 hardly anyone could work or learn from home. The Eisenhower administration focused instead on finding a vaccine as soon as possible (which it did).

Disasters have a human element and that includes bad decision-making

Ferguson’s main topic was the bad decision-making that forms the human contribution to a disaster. Even a volcanic eruption is, in one sense, a man-made disaster: “If you have built a bloody great city at the foot of the volcano and then rebuild it after the eruption, which is of course, something that happens in many parts of the world…”

We are told that the lava flow is slow enough that residents could escape, in the event of an eruption…

He added, “a critical and controversial part of the book was the argument that it was much too easy last year to lay the blame for the political mistakes that led to excess mortality on a few populist leaders. And I won’t waste time naming them.”

One reason Ferguson thinks we misunderstand the nature of the human element is that we lay the blame on the guy at the top when the real failures are often lower down:

I argue in the book that it’s a common failure of analysis to lay the blame on the person at the top. When the space shuttle Challenger blew up shortly after launch, an event that many of you will remember seeing on television, there was an initial attempt by the Washington Post and the usual suspects to blame it on Ronald Reagan. Because that’s what the press does. They tried to argue that the shuttle launch had been rushed so that Reagan could mention it in a speech.

But a great scientist, Richard Feynman, showed that that wasn’t remotely true. That in reality, the engineers at NASA had always known that there was a one in a hundred chance that the thing would blow up because of leaks from the fuel tanks. They also knew that it was more likely to blow up on a cold day than on a hot day because the legendary O-rings would shrink in cold weather and make the fuel leak more likely.

Why was that one-in-a-hundred probability not more widely known? Because the NASA bureaucrats concealed from the people funding the program that that was what the engineers thought. The NASA bureaucrats, including the enigmatic Mr. Kingsberry, turned it into a one-in-a-hundred-thousand chance that the thing would blow up, which is really rather a different risk.

I want to argue, as I did in the book, that we had our own “Mr. Kingsberry.” The real cause of the excess mortality in the United States last year was a terrible failure by the public health bureaucracy who had a pandemic preparedness plan, 36 pages long. I’ve read it; it looks good on paper. The U S was rated as the Number One country in the world for pandemic preparedness in 2019.

But the people who were responsible for the planning, including Robert Cadillac, the assistant secretary for preparedness — who had this one job — knew that the plan was worthless.

In any event, no one was listening. Meanwhile, countries next door to China — South Korea and Taiwan — controlled the epidemic much better via rapid testing, contact tracing, and quarantine of affected individuals.

“That’s why only 12 people died of COVID in Taiwan in 2020,” Ferguson told the audience, “We completely failed to do any of that, completely failed. In fact, the Centers for disease control successfully prevented any other agencies, public or private from producing tests, and then produced a test kit of their own.

He concluded by noting that one outcome of the abnormal social situation created by any pandemic is social unrest: “Often in times of plague or other kinds of disaster, you get great waves of protests, sometimes of a religious character, sometimes of a secular political character,” an apparent reference to the “Summer of Love” riots of 2020.

You may also wish to read: Explosive new information about New York’s mass COVID deaths. In a video conference, perhaps accidentally, a health official blurted out the deadly policy and the reasoning behind it. Fearing political pushback, New York officials took steps to conceal from the federal government the policy that doomed thousands of seniors. (Michael Egnor)