For Five Days There Was Free Expression in China

Then censors blocked the Clubhouse app

In March 2020, Silicon Valley entrepreneur Paul Davidson and former Google engineer Rohan Seth launched their newest app, Clubhouse. The app is an invite-only audio chat app that lets users talk in virtual rooms. These conversations can be one-on-one or they could have an audience of up to 5,000 users (the current room limit in the beta version of the app). The app is only available on the iPhone and, once invited, users must use their actual phone number and Apple ID to join. Each user is only allowed to invite up to five people.

The app’s exclusive nature gave it the tantalizing aura of the “next-big-thing” among the tech types. On January 31, Space-X’s Elon Musk made an appearance on the app to discuss Mars missions, COVID, GameStop stock, and other hot topics. On February 4, Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg also dropped in.

One attractive feature of Clubhouse is it doesn’t keep a record of the conversations. That enables semi-private conversations (participants can record them). After Musk’s and Zuckerberg’s visit to the app, mainland Chinese, Taiwanese, Hongkongers, Uyghurs living abroad, and others flocked to the app. Some even bought invites on Taobao (China’s online shopping site) for up to US$46. Many saw Clubhouse as an opportunity to talk to people in a way that they usually could not about taboo topics in China, such as Tiananmen Square, Taiwan independence, and the treatment of the Uyghurs in the Xinjiang province: “These five days show how possible it is for Taiwan and China to communicate and interact with each other in a normal way,” said Ken Young, based in Taiwan, who moderated some of the discussions. “It was only five days, but it’s like a hundred flowers bloomed.” (Washington Post, February 8, 2021)

Problems arose because the real-time audio/visual support for the Clubhouse app is provided by a China-based company called Agora. On that account, many users were concerned that the app would be banned— or worse, that they would be punished for their involvement in the conversations. Agora assures its clients that audio and visual data are encrypted and that its cache is deleted after 10 seconds. Still users were concerned that they would be identified by their audio fingerprint if someone recorded the conversation. It’s not an unrealistic concern: China is at the forefront of voice recognition software, which is developed by iFlytek.

The “Rooms”

Several rooms at Clubhouse were dedicated to civil discussions where people can voice their perspectives without fear of using language that was not politically correct. China Digital Times translated several social media posts from people who participated in the discussions. One user characterized the experience on Weibo:

No one was aggressive when speaking. And no one was correcting other people’s preferred phrases for the sake of being “politically correct.” When many people from Taiwan used “China” rather than “Mainland” or “Inland,” no one raised objection. That’s because the audience in this realm can understand that people have different thoughts and habits due to differences in history, culture and education…Thousands have participated in tonight’s discussion. How many will they go on to influence? This is going to have a huge impact… I don’t know how long this environment can last, or whether it will reappear. But I will definitely remember this epic moment on the internet.

John Chan, “Translation: Clubhouse Blocked in China; Anticipation and Reactions” at China Digital Times (February 8, 2021)

On Facebook, one user said of the discussions on Xinjiang and Uyghurs being placed in detention camps by authorities:

The deepest discussions happened between four and eight in the morning. In the beginning, I wasn’t able to fall asleep. Later, I dared not sleep. At some point, Xinjiang people living overseas were crying because they didn’t know where their family was. Then some Han people were crying because it was their first time hearing all this and they were struck by guilt. And a participant who still lives in Xinjiang begged others not to release her information: “I am really scared… really, really scared ….” I can say no more.

John Chan, “Translation: Clubhouse Blocked in China; Anticipation and Reactions” at China Digital Times (February 8, 2021)

According to Zeng Jiajun, a former tech worker, “Hearing someone’s voice can make both sides realize we’re all human.”

One room was dedicated to Li Wenliang (1986–2020, pictured), the ophthalmologist at Central Hospital of Wuhan who died on February 7, 2020, from COVID-19. He is heralded as the first whistleblower to alert the public about the SARS-like pneumonia he was seeing at the hospital. He was punished by authorities for illegal activities. The room was silent on the anniversary of his death.

The Censors Swoop

The app was shut down by Chinese Communist Party censors on February 8 at 7PM (Beijing time). At the time, there were many people in the rooms touting Chinese Communist Party propaganda and saying that the meetings were one-sided and anti-China. Some critics said Clubhouse was “planted by Western countries to brainwash credulous young Chinese,” according to The Washington Post.

Many users knew that Clubhouse would get censored. The app was removed from the China Apple Store in December. On Monday, February 8, the app’s API was blocked within mainland China. Users with a VPN and an overseas Apple ID could still access the app, but with limitations. According to TechCrunch:

Hours before the ban, Global Times, a Chinese state-backed newspaper that is thought to at times represent views of the country’s leaders, published an article titled “Clubhouse is no ‘free speech heaven,’ say Chinese mainland users” and quoted users who described the app as a platform where “anti-China” comments flowered.

Darrell Hetherington, Rita Lao, “Clubhouse is now blocked in China after a brief uncensored period” at TechCrunch

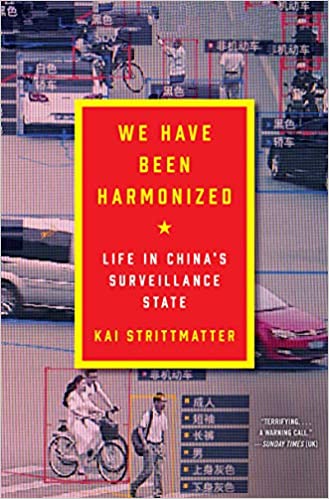

The excitement and sense of fellowship expressed by Chinese Clubhouse users recalls the sentiments expressed when Sina Weibo launched in 2009. Journalist Kai Strittmatter, in his book We Have Been Harmonized, recounts the early days of Weibo as a realm of unprecedented freedom, especially for China’s young, urban generation (page 68). However, by 2013, when the Chinese government became more authoritarian under Xi Jinping, taboo topics on Weibo were censored and people with too much influence were banned from the site.

Strittmatter interviewed Murong Xuecun, a writer who was one of the first bloggers on Weibo to get banned by the CCP. Murong told him, “Like all authoritarian systems, this one depends on the fact that you are a lone person faced with an overpowering organization, and you capitulate. Since Weibo arrived, that no longer works. People are forming networks.” Which is why, according to the CCP, the free expression of ideas had to be stifled then, just as now. It is dangerous.

As Melissa Chan, who wrote about the end of Clubhouse in China in Foreign Policy said on Twitter, “And possibly my biggest takeaway about Clubhouse is how much the experience underscores how we’re ALL victims of the Chinese state, that doing an ordinary thing like sharing feelings had to be this special thing — even those living outside China felt this trauma.” (February 8, 2021, full thread)

Note: The photo of Li Wenliang (1986–2020) is fair use.

You may also wish to read:

Mulan: Disney talks freedom at home, toes the line in China. Films we see get altered in subtle and not-so-subtle ways to conform to the requirements of CCP propaganda. (Heather Zeiger)