But Do “Hidden Webs of Information” Really Solve Life’s Mystery?

Cosmologist Paul Davies won an award last year for an attempt that left “more questions than clean-cut answers (Physics World)

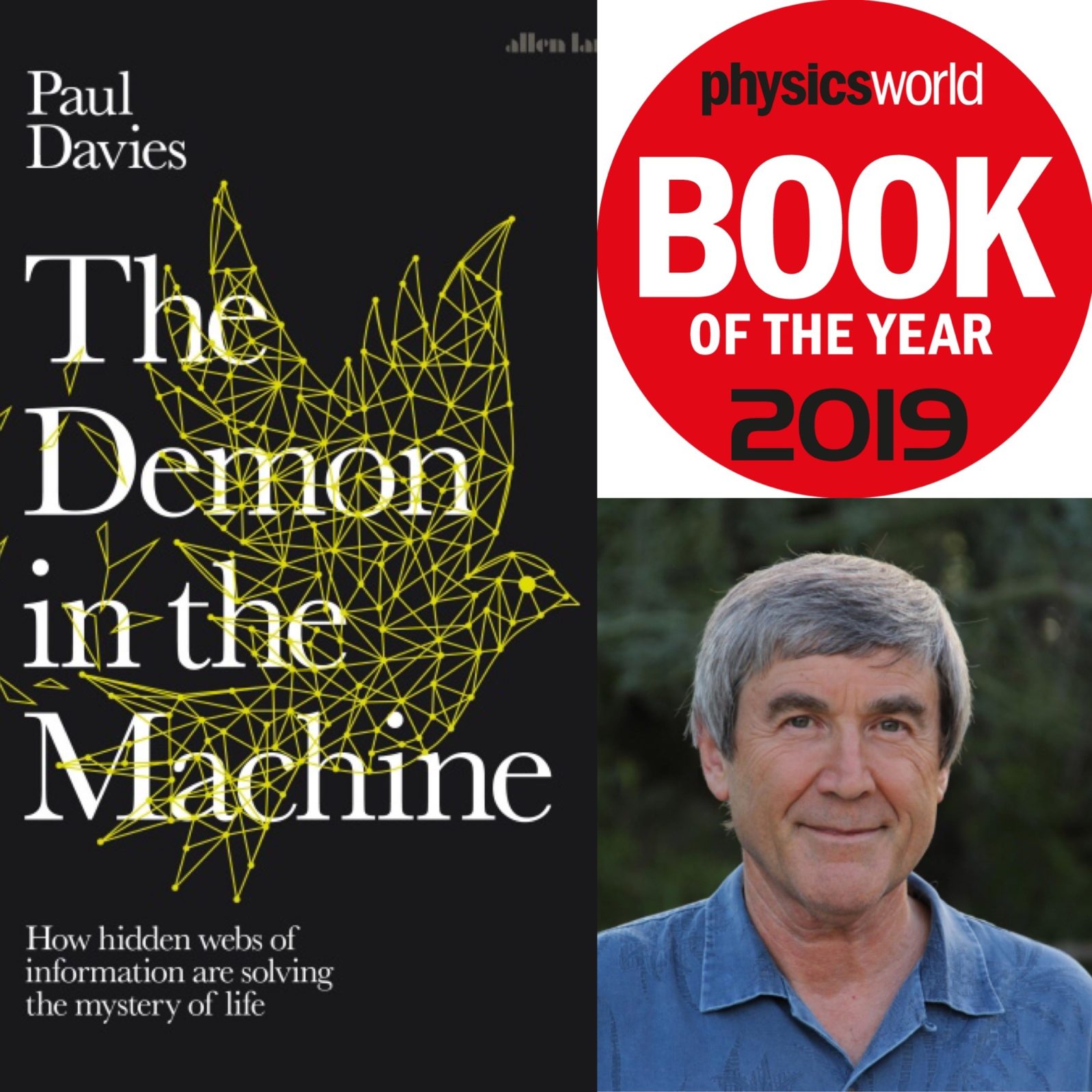

Last year, State University of Arizona’s cosmologist Paul Davies won a Best Book award from Physics World for Demon in the Machine:

The book’s subtitle is “How hidden webs of information are solving the mystery of life.” But are they?

The book deals with established physics concepts (such as the second law of thermodynamics), but also delves into Davies’ thoughts on topics such as the emergence of human consciousness (while making sure the reader is aware of what is speculation). Readers, though, are likely to be left with more questions than clean-cut answers about the laws of nature.

“Just in the last 10 years or so, I suppose, I’ve begun to see a confluence of different subjects. Partly, this is advances in nanotechnology, said Davies when he spoke to Physics World earlier this year. “Partly, it is a convergence of physics and computing and biology and information theory – all these subjects are coming together in the realm of large molecules or tiny machines, where life and chemistry and physics all intersect. That’s the new frontier – the physics of the very complex, where the traditional subject boundaries melt away.”

Tushna Commissariat, “The Demon in the Machine by Paul Davies wins Physics World Book of the Year 2019” at Physics World (December 18, 2019)

It’s a great idea but if we look at the problems, they all occur at the boundaries—which makes them difficult to solve because they are not contained by anything. The boundary signals something different.

How about, for example:

➤ Information: Unlike matter and energy, information is immaterial. “ It exists, among other things, as a relationship between realized and unrealized possibilities.” Information governs.

➤ Origin of life: Life forms are overwhelmingly full of information and theories as to how that got started are really not very good. “There are few bigger — or harder — questions to tackle in science than the question of how life arose.” (Quanta, 2015) Nothing has changed since then.

➤ Consciousness. We are, for example, told that:

To discover what makes us self-aware, researchers from around the world are going head-to-head in a grand competition to determine where consciousness really comes from.

There are many consciousness theories, it’s just that none is widely accepted. Part of the reason is the two-tiered nature of the challenge. There’s what the Australian philosopher David Chalmers called the ‘easy problem’ of consciousness, which is explaining the biological processes that underlie mental functions, like perception, memory and attention.

But there’s also the ‘hard problem’, which is explaining how and why there is a subjective, first-person aspect to these mental functions (why, when you stub your toe, you don’t simply register the damaging contact – it actually hurts). Scientific theories of consciousness particularly struggle with the hard problem – in fact, there’s disagreement about whether there really is a hard problem at all.

Christian Jarrett, “Consciousness: how can we solve the greatest mystery in science?” at BBC Science Focus (April 5, 2020)

In other worlds, it’s another boundary mystery.

About the business of claiming that there might not be a “hard problem at all”? Philosopher David Papineau, to take one example, simply insists that if we “just shed the idea that there is any significant distinction between the mind and the brain, the notorious hard problem of consciousness would disappear:”

Sure, and if we just shed the idea that there is any meaningful difference between humans and chimpanzees, a lot of other hard problems would just disappear too. As if life were so simple.

It will be interesting to see who wins the prize this year.

You may also enjoy:

Philosopher: Consciousness is not a problem. Dualism is!