Computer Science Prof: The Turing Test Was Not About Intelligence

The aim was to pretend intelligence, to fool people. That makes a big difference when we ask whether computers can become intelligentComputer science prof George Montañez of Harvey Mudd college pointed out here a couple of years ago that the famed Turing test for computer intelligence originated as Alan Turing’s riff on a 1940s party game, the imitation game: “…you had two people in different rooms. One of them, a man, one of them, a woman, and party guests would try to ask questions of these various parties and guess which one was the man, and which one was the woman. So, essentially, both would pretend to be a woman and you would try to differentiate which one was actually a woman based on the responses given.”

The concept of when computers would “pass the Turing Test” so dominated public discussion that commentators seem to have largely forgotten that Turing (1912–1954) aimed at imitation, not reality.

That has profoundly impacted the direction in which the AI industry has gone, says Queens University (Belfast) computer engineering prof Deepak P. He reminded us at Aeon last week,

It is noteworthy that Turing had called it the ‘imitation game’. Only later was it christened the ‘Turing test’ by the AI community. We don’t need to go beyond the first paragraph of Turing’s paper ‘Computing Machinery and Intelligence’ (1950) to understand the divergence between the ‘imitation game’ and judgment of whether a machine is intelligent. In the opening paragraph of this paper, Turing asks us to consider the question ‘Can machines think?’ and he admits how stumped he is.

He picks himself up after some rambling and closes the first paragraph of the paper by saying definitively: ‘I shall replace the question by another, which is closely related to it and is expressed in relatively unambiguous words.’ He then goes on to describe the imitation game, which he calls the ‘new form of the problem’. In other words, Turing is forthwith in making the point that the ‘imitation game’ is not the answer to the question ‘Can machines think?’ but is instead the form of the replaced question.

Deepak P., “Mere imitation,” Aeon, August 8, 2024

So, in a move familiar to us from politics and other games, Turing substituted a question he could more easily answer:

That was fine as long as the switch was recognized. But apparently, it wasn’t:

The AI community has – unfortunately, to say the least – apparently (mis)understood the imitation game as the mechanism to answer the question of whether machines are intelligent (or whether they can think or exercise intelligence). The christening of the ‘imitation game’ as the ‘Turing test’ has arguably provided an aura of authority to the test, and perhaps entrenched a reluctance in generations of AI researchers to examine it critically, given the huge following that Turing enjoys in the computing community.

Deepak P., “Mere imitation”

Professor P. goes on to discuss the way mathematicians later sidelined philosophers and psychologists on the topic of what “intelligence” consists of. That meant they had to determine what counts as success in developing human-like intelligence, while using a test that measures only the ability to imitate. The defects of that approach have become evident:

The AI that had started to excel at checkers and chess through symbolic methods wasn’t able to make progress in distinguishing handwritten characters or identifying human faces. Such tasks are what may fall within a category of innately human (or, well, animal) activities – something we do instantly and instinctively but can’t explain how. Most of us can instantly recognise emotions from people’s faces with a high degree of accuracy – but won’t be enthusiastic about taking up a project to build a set of rules to recognise emotions from people’s images. This relates to what is now known as Polanyi’s paradox: ‘We can know more than we can tell’ – we rely on tacit knowledge that often can’t be verbally expressed, let alone be encoded as a program. The AI bandwagon has hit a brick wall.

Deepak P., “Mere imitation”

The mythmaking continues, spurred on by chatbots, even as the limitations (model collapse and hallucinations) come to be clearly seen as features, not bugs, in systems that have no innate intelligence that could weed them out:

The availability of LLMs since the release of ChatGPT in late 2022 heralded a global wave of AI euphoria that continues to this day. It was often perceived in popular culture as a watershed moment, which indeed it could be, on a social level, since AI never before pervaded public imagination as it does now. Yet, at a technical level, LLMs have machine learning at their core and are technologically generating a newer form of imitation – an imitation of data; this contrasts with the conventional paradigm involving imitation of human decisions on data.

Deepak P., “Mere imitation”

There have been advances for sure but, as Eric Holloway pointed out here at Mind Matters News last month, these advances don’t put machines on the path to human intelligence: “And this is the way it will always be unless we come up with some new computer paradigm that does not rely on logic gates applied to 1’s and 0’s. Yet a new computer paradigm is impossible, to the best of our knowledge.”

In other words, computation isn’t the only process involved in thinking but computation is the only process computers can do. Better imitation of non-computational thinking is not a step on a road to non-computational thinking as a reality.

Professor P. reminds us,

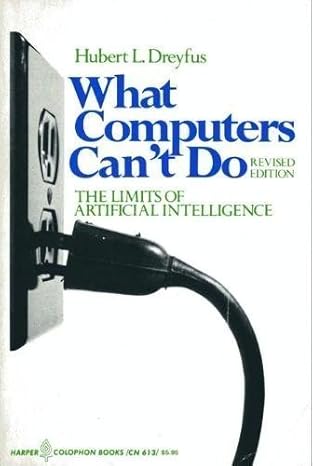

As Hubert Dreyfus wrote in What Computers Can’t Do (1972), ‘the first man to climb a tree could claim tangible progress toward reaching the moon’ – yet, actually reaching the Moon requires qualitatively different methods than tree-climbing. If we are to solve real problems and make durable technological progress, we may need much more than an obsession with imitations.

Deepak P., “Mere imitation”