Neuroscientist: The Mind Is Just the Brain

He cites studies using transcranial magnetic stimulation, which caused subjects to see flashing lightsUniversity College (London) neuroscientist Patrick Haggard told Robert Lawrence Kuhn in a February episode of Closer to Truth, “I have no problem with the idea that consciousness simply is the activity of particular brain circuits.”

In philosophical terms, he is comfortable with identity theory — though he doesn’t like to be “forced into a corner” by philosophers.

How does he defend his view? Here’s “How Brain Scientists Think About Consciousness” (7:12 min):

Excerpts from the transcript:

Haggard: Well, I think [0:18] that consciousness is a consequence of brain activity. So the brain consists of billions and billions of neurons. Each of which is a living cell which is capable generating an electrical impulse, a synapse to other neurons, and in some cases assemblies of these neurons can produce a conscious feeling. Now, not all brain activity produces consciousness. But some brain activity does produce consciousness and I think consciousness is, it’s great to have it, it’s a wonderful and possibly even transcendental thing from the first person perspective but it’s it’s also the product of that very complex and very fantastic machine that is the human brain.

Note: We have leapt from billions of billions of neurons to consciousness without any intervening explanation. The effect is somewhat like going from millions and millions of bricks to a cathedral complex without any intervening architect or building crew. Perhaps Haggard senses this because he goes on to say …

Haggard: Some of the neural circuits in some areas of the brain seem to be particularly likely to cause consciousness and we can think about the cerebral hemispheres the neocortex which is the big bit as being more intimately concerned with our feelings, our sensations, our perceptions and our thoughts than lower brain areas of brain stem and the midbrain. So there’s something about the cortical circuit, with its layered structure and its complicated neuron interconnections between neurons which seems to make it well suited for producing consciousness.

Note: But what is the “something” that makes the neocortex well suited to producing consciousness? We don’t hear about that. But then, philosophers are split over what consciousness even is.

Later in the interview, Haggard explains how a certain type of experiment with the human brain can cause consciousness:

Haggard: So there are a few ways in which we can [5:01] intervene in the human brain. One of them is a very important technique called transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS). So it basically consists of making neurons in the superficial layers of the cortex fire by exposing them to a brief but strong magnetic field.

Now, over some [5:17] areas of the brain — not all — you can produce a conscious experience by artificially activating the brain using transcranial magnetic stimulation. So if you stimulate over the visual cortex, you can make people see flashes and as you move the coil around the different bits of the visual cortex, they’ll see a flash in different parts of their visual field. If you hold the coil over the bits of the brain that process the movement of visual stimuli, they’ll see a flash that whips across their visual field like a lightning bolt. I think that’s a really beautiful demonstration that making neurons fire in this case artificially causes conscious experience.

Readers may disagree but that doesn’t sound like a very significant example of “causing” conscious experience. The subject experiences the TMS as a flash of light. But if consciousness did not already exist, there would be no experience at all.

At Kuhn’s suggestion, the discussion turns to identity theory itself

Haggard: The interesting feature about [6:36] identity theory is that you’re then saying there’s an identity between a necessarily first person experience and a clearly objective set of neurophysiological events. And that really means, I think, saying, well maybe the first person perspective isn’t actually that important in the end because the biological machine can generate it. Maybe that’s quite a useful and humble thing to admit.

﹋﹋﹋﹋﹋﹋﹋﹋﹋﹋﹋﹋﹋﹋

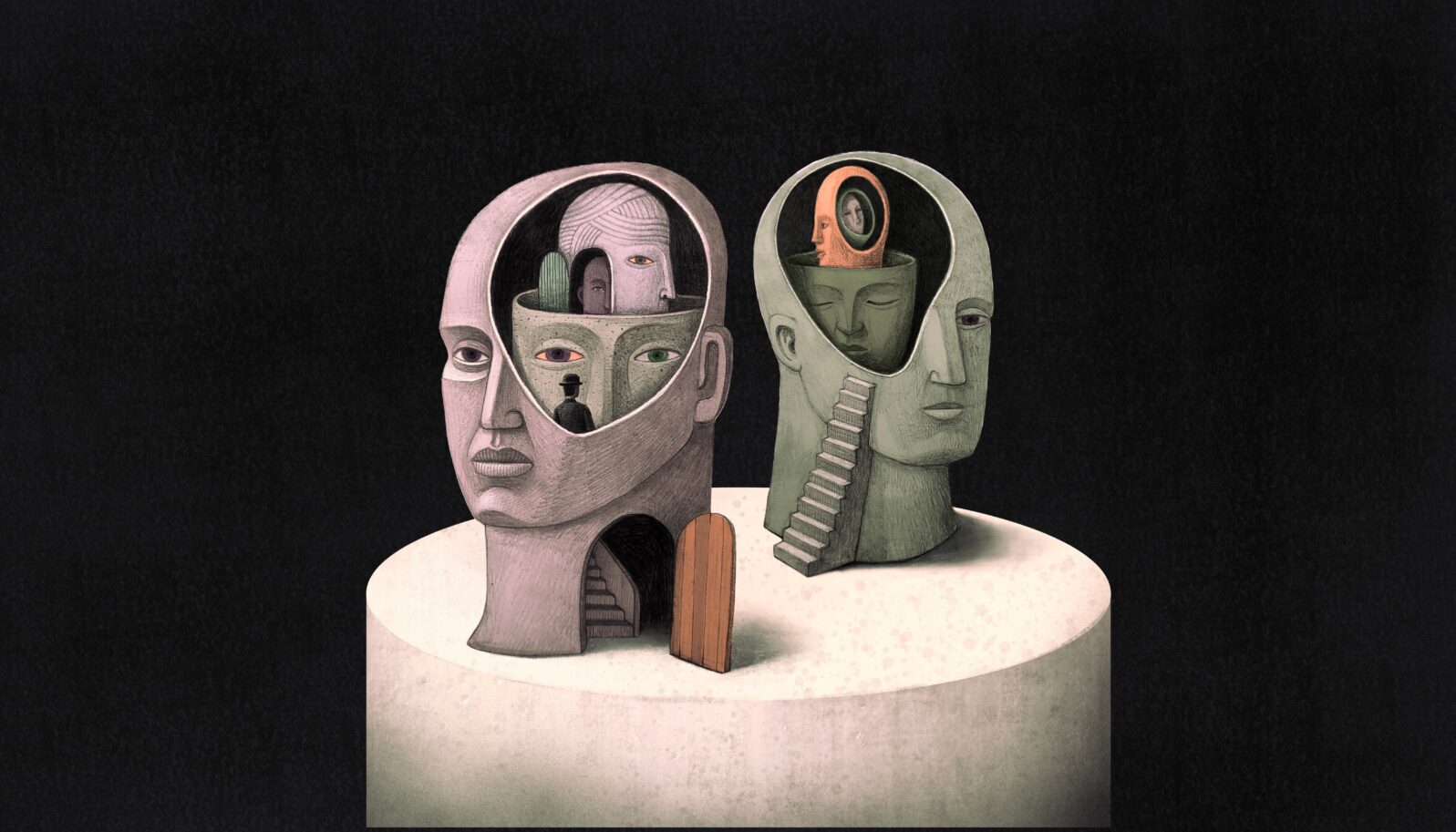

When the claim that consciousness simply is the activity of particular brain circuits is evaluated logically, a serious problem arises. As neurosurgeon Michael Egnor has noted, there is no obvious relationship between mental and electrochemical states.

Here is a simple example: Suppose you decide that it costs so much to rent a bike frequently that you may as well buy one. The relationship between your mental states is logical: You contemplate the costs in each case and decide based on the math.

Whatever is happening in your brain at the time you are thinking about that is electrochemical. But there is no contact between the laws of logic and the laws of electricity and chemistry. They share no properties in common. The mind has ideas and feelings and the brain has neurons and glia.

That problem has limited the popularity of identity theory. It sounds good in a naturalist (nature is all there is) environment but — like all such theories — it doesn’t eliminate the mind. It just lets the mind get clean away.