Will Neuralink’s Brain Implant Help Paralysis Victims?

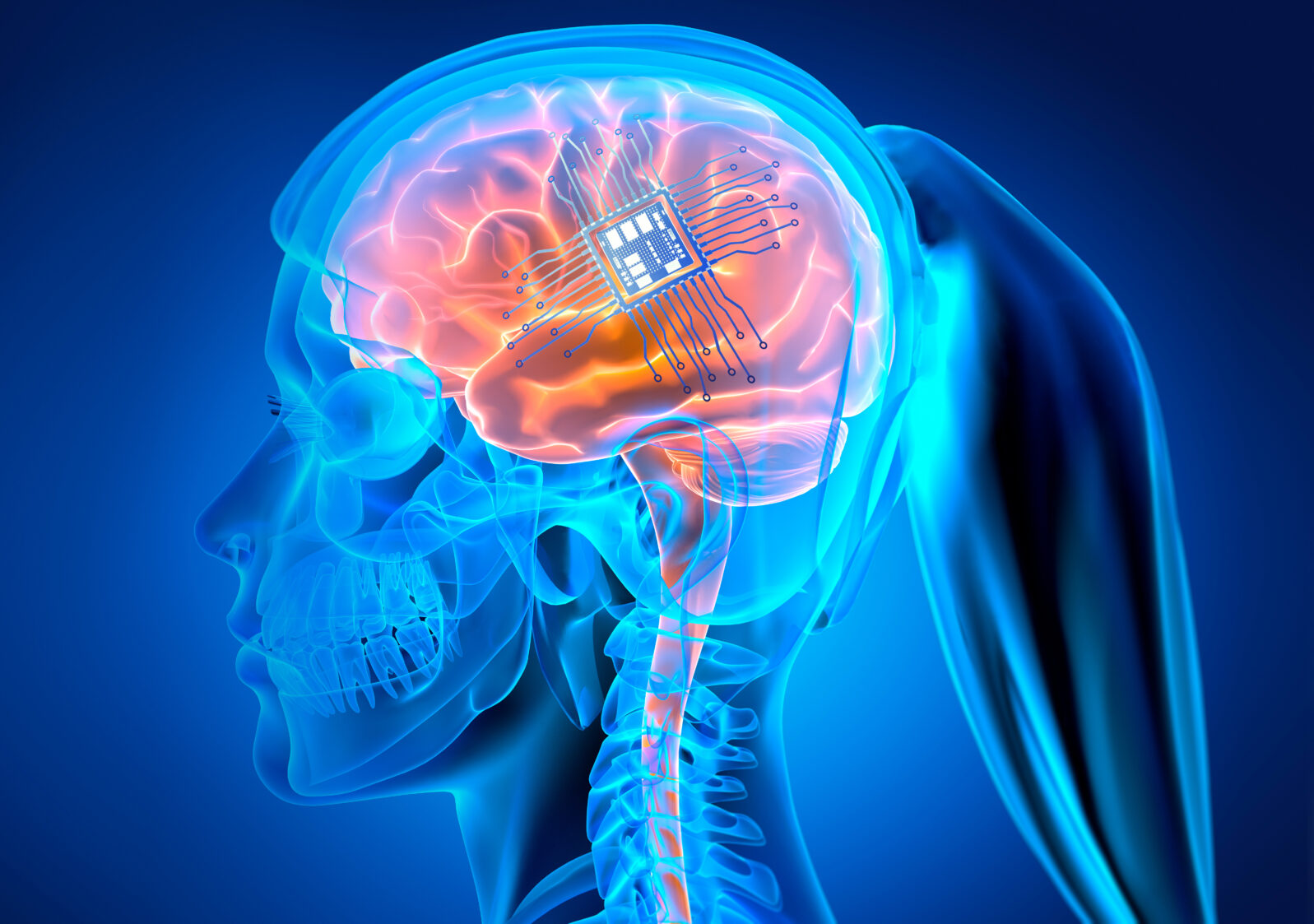

Addressing disabilities like paralysis, limb loss, and blindness seems a more realistic goal than the hyped (and feared) human–machine hybridsNeuralink, founded by tech entrepreneur Elon Musk in 2016, recently announced that it has developed a device for a brain–computer interface (BCI) called “Telepathy.” As explained at Nature, “BCIs record and decode brain activity, with the aim of allowing a person with severe paralysis to control a computer, robotic arm, wheelchair or other device through thought alone.”

Such implants began to be used about 20 years ago and the underlying principle is quite simple: The human brain is an electrical system and neurons can thus send and receive signals coordinated with electronics.

Considerable work has been done in the recent past to treat paralysis, limb loss, and blindness through BCI. In fact, some go so far as to claim that Neuralink’s Telepathy is not as advanced as four other models. However, it is surely the one with the most financial backing and media buzz — therefore most likely to put the idea on the public’s mind map.

Industry watchers are frustrated by a lack of information

From Nature:

There has been no confirmation that the trial has begun, beyond Musk’s tweet. The main source of public information on the trial is a study brochure inviting people to participate in it. But that lacks details such as where implantations are being done and the exact outcomes that the trial will assess, says Tim Denison, a neuroengineer at the University of Oxford, UK.

The trial is not registered at ClinicalTrials.gov, an online repository curated by the US National Institutes of Health. Many universities require that researchers register a trial and its protocol in a public repository of this type before study participants are enrolled. Additionally, many medical journals make such registration a condition of publication of results, in line with ethical principles designed to protect people who volunteer for clinical trials. Neuralink, which is headquartered in Fremont, California, did not respond to Nature’s request for comment on why it has not registered the trial with the site.

Liam Drew, “Elon Musk’s Neuralink brain chip: what scientists think of first human trial,” Nature, 02 February 2024

Here’s Neuralink’s outreach to the public at large, recruiting volunteers for a study:

What advances does Neuralink offer?

Neuralink’s system, which does not need a physical connection to a computer, targets individual neurons. Other systems average responses from a number of neurons.

Musk says that the implanted patient is “recovering well” and that “initial results show promising neuron spike detection” but, as we are cautioned at Wired, “it could be months before we know whether the patient can successfully use the implant to control a computer or other device.”

Science writer Emily Mullin, also offers more details at Wired, about ways in which Telepathy is a technical advance over earlier systems:

Until recently, BCIs were largely pursued by academic labs. They required clunky setups using thick cables that made them impractical to use at home. Neuralink’s system is designed to be wireless and records neural activity through more than 1,000 electrodes distributed across 64 threads, each thinner than a human hair. The most common device used in BCI research, the Utah array, records from 100 electrodes.

Emily Mullin, “Elon Musk Says a Human Patient Has Received Neuralink’s Brain Implant,” Wired, January 29, 2024

First step toward cyborgs?

Musk doesn’t deny that he would like to merge humans with computers, such that we could, say, merge with our phones. But, realistically, most people are waiting to see how much difference Telepathy and similar devices like Synchron, backed by Jeff Bezos and Bill Gates, will make to people with disabilities.

Nathan Copeland, who lives with paralysis from the chest down, is a fan, based on his response to a Neuralink presentation: “I thought it was really cool, and for a moment there I was maybe kind of jealous of the person that ends up with one of these things, assuming it works, and gets to do all the cool stuff and be the new rock star of the BCI world.” The technology he himself was using when interviewed by MIT’s Technology Review (July 19, 2019) is called Utah arrays. As the video shows, he is using the implant to control an exoskeleton in order to eat:

At The Federalist, senior editor John Daniel Davidson warns, it won’t stop here: “The goal is to usher in a transhuman future by creating human-machine hybrids that will be “superior” to natural or non-enhanced humans.”

Meanwhile, Anne Vanhoestenberghe, a King’s College London professor of “active implantable medical devices,” counsels a wait-and-see approach: “We know Elon Musk is very adept at generating publicity for his company, so we may expect announcements as soon as they begin testing, although true success in my mind should be evaluated in the long-term, by how stable the interface is over time, and how much it benefits the participant.” (Independent, January 30, 2024)

Assuming that the technology is shown to work after widespread, long-term use among people with disabilities, it’s a separate question whether very many people would want that intimate a relationship with their phones.