Yes, Plants Do Communicate — But Is It a One-Way Street?

Are we straining the meaning of the term “communication” by overinterpreting what we observe?In recent years, we have seen a welcome recognition that plants, like animals, have complex interrelationships, which include picking up information. Some have taken the discovery very far indeed. Plant research scientist Matthew Hall thinks that we should see plants as ”other-than-human persons.”

Similarly, Saitama University plant communications researcher Masatsugu Toyota offers,

Plants “can sense a variety of stimuli in the environment. They can smell and they can sense touch, and they can communicate with each other. There is no border between animals and plants,” Toyota said.

“I really want everybody, especially kids, to understand that plants are very sensitive. Please be gentle to all the plants outside,” he said.

Maiya Focht, “Plants can talk to each other and scientists say it should make us rethink how we treat them,” Business Insider, Jan 31, 2024

Gentleness is a good thing but there is in fact a border between animals and plants; generally speaking, animals are mobile and plants are not. Some might argue that that is just an accident. But it is an accident with consequences: Animals can access many strategies in dealing with their problems that are not generally available to plants (running, swimming, and flying come to mind). That probably influences the way in which communication develops.

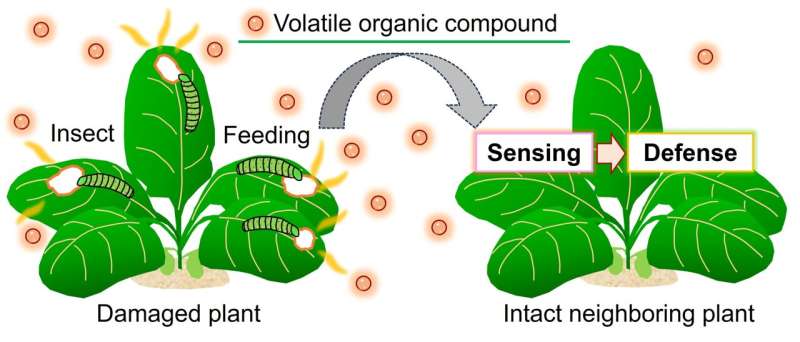

Last year Toyota’s lab published an open-access paper showing how plants pick up the airborne chemical signals — volatile organic chemicals (VOCs) — emitted from the leaves of other plants that are under attack by insects:

Undamaged neighboring plants sense the released VOCs as danger cues to activate defense responses against upcoming threats. This phenomenon of airborne communication among plants through VOCs was first documented in 1983 and has since been observed in more than 30 different plant species. However, the molecular mechanisms underlying VOC perception to defense induction remain unclear.

Saitama University, “Real-time visualization of plant-plant communications through airborne volatiles,” Phys.org, October 17, 2023

The plants also responded to VOCs emitted from smashed leaves.

UC Davis entomologist Richard Karban has likewise found that

… sagebrush plants sound the alarm when they’re attacked by pests so that other sagebrush plants respond by growing faster and stronger. Even other species, like tobacco, can sense and react to the alarm.

“These volatile chemical cues are one potential source of reliable information for plants,” Karban says. “What’s still unclear is how general this is, how universal it is among plants and just how important it is.”

Sofia Quaglia, “Is Plant Communication a Real Thing?” Discover Magazine, Apr 28, 2023

But is it really communication in the “animal” sense?

The process Toyota and Karban describe has been called “plant eavesdropping” — which raises an interesting question. When humans eavesdrop, we are listening to a communication that is not intended for us. We could in fact be listening to a woman alone, expressing her thoughts to herself out loud.

So, we might ask, to what extent are other plants picking up a chemical odor that was emitted naturally — not in any way intended as a signal — and responding to it mechanistically by running similar chemicals of their own? If our original model for communication is animal behavior, the meaning of the term “communication” is somewhat strained.

For example, when a cat reflexively assumes a defensive posture (arched back, spitting, piercing cries, bared claws), its autonomous nervous system is communicating a message to a would-be attacker: Beware the cat! A formidable and dangerous creature!:

That’s not particularly true. But in the instance above (as in many others), the cobra understood and responded to the deceptive message by retreating after a few well-placed swats. In other words, much communication in the animal world is a much more complex affair than what Dr. Toyota has documented in plants.

Plant communication is a field well worth pursuing but Sofia Quaglia offers a qualification at Discover. Books like The Secret Life of Plants (Harper & Row 1973), which made claims for plants’ “surprising reaction to music, their lie-detection abilities, their creative powers, and much more” did not help the science credibility of the field.

That aside, learning more about plant ecology, could result in some useful discoveries. For example, one team reported last year that hybrid tomatoes, bred for ease of processing, were less likely to emit strong VOC signals than heirloom varieties are. If so, retaining that capacity during the breeding process could enable growers to reduce the use of pesticides. But it’s early days yet in terms of serious study.

You may also wish to read: Researchers: Yes, plants have nervous systems too. Not only that but, like mammals, they use glutamate to speed transmission

and

Scientists: Plants are not conscious! No, but why do serious plant scientists even need to make that clear? What has happened? Quite simply, the need to see humans as equivalent to animals has now spread to the need to see us as equivalent to plants.