Seductive Optics and Skeuomorphic Intelligence

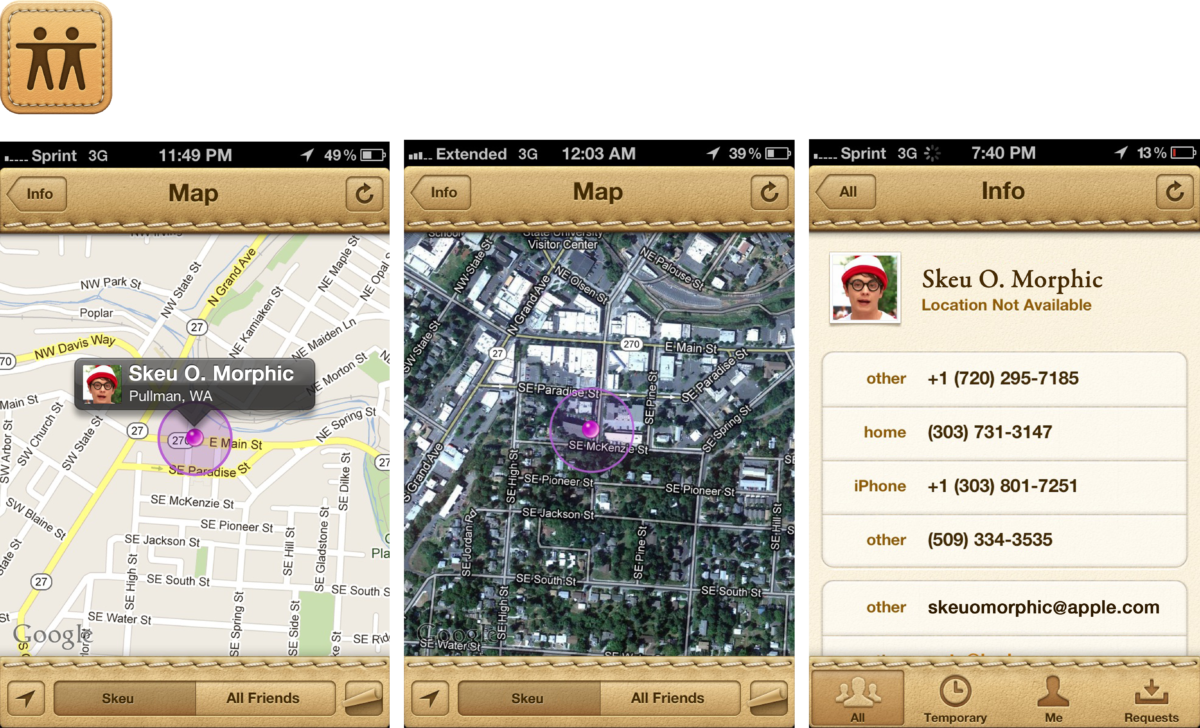

Appearance and reality in art and artificial intelligenceThings are not always as they seem. Artificial intelligence is like that. Steve Jobs famously directed Apple’s designers to precisely imitate the napa leather seats in his Gulfstream jet to adorn the iCal app. The result was a seemingly supple and needle stitched interface that, nevertheless, felt like glass. The interface for the iPhone was famous for these expertly crafted, “lickable” icons that were rendered with artificial shadows and depth. Skeuomorphism became the term of art for this habit of borrowing design cues from the physical world to make their digital counterparts attractive and recognizable. In time, designers embraced “flat design”, a style ostensibly more suited to its medium. But the faux leather and superficial resemblances carry on.

Skeuomorphism, as wonky as it sounds, is a simple concept. It’s the idea that new designs retain ornamental elements of past iterations no longer necessary to the current objects’ functions. You see this often in Apple’s software: The Notes app is presented as a yellow legal pad, while Game Center is modeled after a Las Vegas-style casino table, with lacquered wood and green-felt cloth.

Austin Carr, “A Former iPhone UI Designer Defends Apple’s Fake-Leather Design Philosophy” at Fast Company

The effort to mirror objects in the world in our artistic creations reaches back into prehistory, from cave paintings and rock sculptures to the latest 3D rendering engine or animatronic sexbot. Whatever the medium, as our tools and skills increase, we are able to make ever more convincing replicas of the genuine article. Today, because of these superficial similarities, we are often fooled into thinking that the artificial intelligence programmed into many of our creations isn’t artificial after all. This misapprehension is the result of being taken in by a magic trick, by a kind of skeuomorphism that Robert J. Marks calls, “seductive optics”. Skeuomorphism is not restricted merely to computer interfaces and virtual artifacts. It is …

… a term which refers to the fashioning of artifacts in a form which is more appropriate to another medium. Archeologists often use it to explain the existence of otherwise inexplicable objects. Some of those might be the fake copper rivets on jeans, long made obsolete by modern stitching. Radiator grilles on electric cars. Plastic hair combs dyed to look like tortoiseshell. A camera phone which emits a shutter-click sound. A modern sports car which must meet noise regulations, but pipes in racy sounds through its speakers to console its driver.

“Who Misses Skeuomorphism” at the Language, Learning and Culture Blog

Painting People

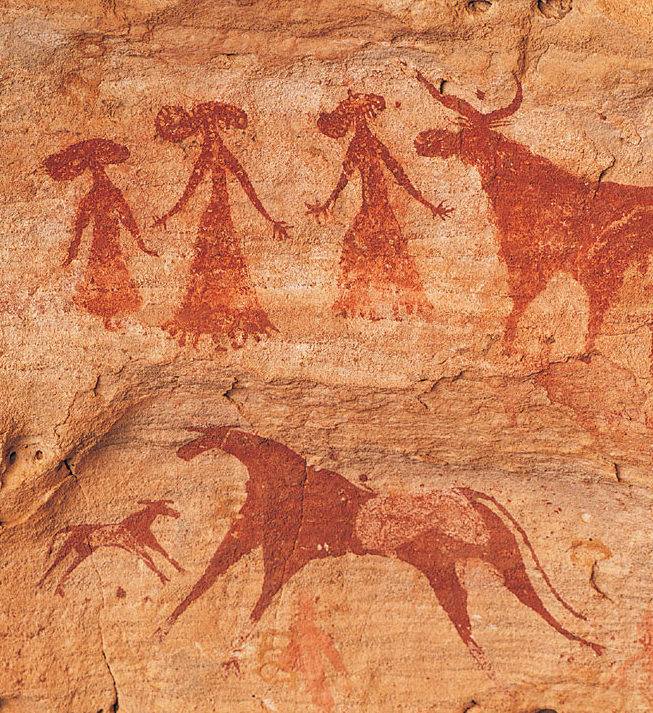

Early humans sometimes depicted the drama of the hunt on cave walls by scraping the rocks or smearing charcoal and pigment. Others assembled or chipped at rocks to make human effigies. Some of these artifacts are more sophisticated than others, showing movement and depth. Still, no one would think these simple caricatures or the rocks themselves shared the conscious lives they represent. These are plainly soulless, lifeless rocks with no thoughts, hopes, or sorrows.

By the late Renaissance, artists had greatly improved their brushes, pigments, and media as well as their understanding of perspective, foreshortening, underpainting, and shadows. Their artworks captured complex scenes and often the mood of their subjects. We may not know the secret thought behind Mona Lisa’s smirk, but Leonardo Da Vinci’s relatable portrayal does make us wonder. Van Eyck’s perfectly painted portraits, with wrinkles and warts, make us feel all the more like we can know something of the subject, or that we can peer with Vermeer into the Girl with the Pearl Earring’s eyes and sympathize with her longings.

Oranges are just one item from an almost infinite list of things seen by Van Eyck with amazing acuity … the textures of fur, flesh, wood, stone and ceramics, the exact pattern of body hair, follicle by follicle, on Adam’s naked body, the precise hue and shape of a wart on a clergyman’s cheek, and so on.

“How Jan van Eyck revolutionised painting” by Martin Gayford at The Spectator (February 8, 2020)

With increasingly formalized training in academies, artists mastered realism. The subjects of French Academic Realism are so true to life that it is hard not to empathize with them, to storm the Bastille with them, or even to lust after them. Seductive optics indeed.

Jan Van Eyck

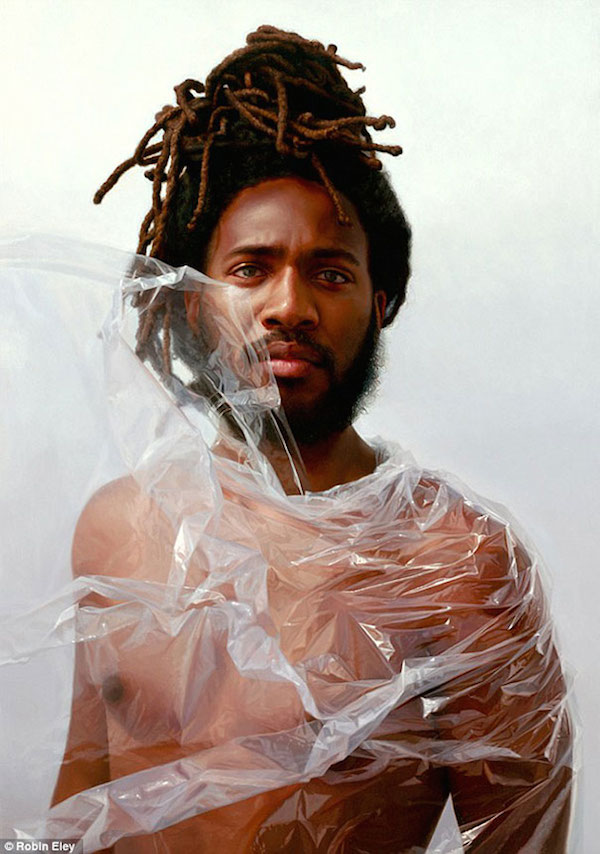

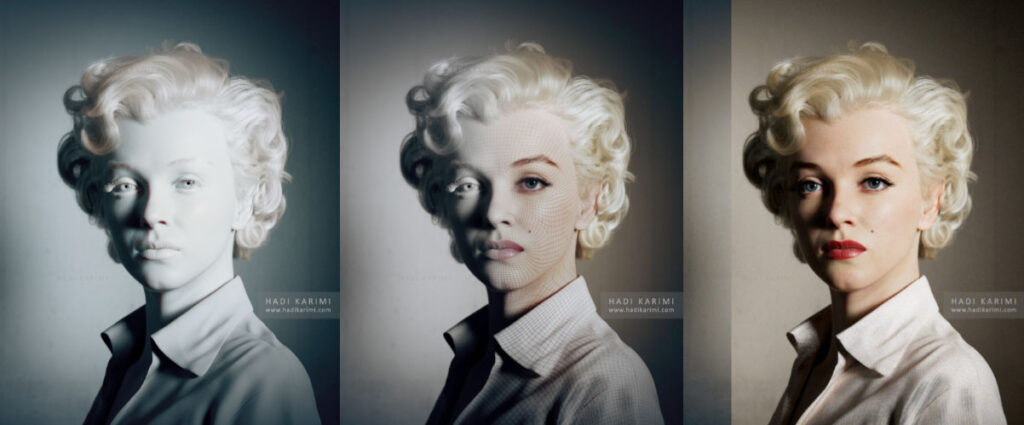

Today, a subgenre of painting and sculpting called hyperrealism goes even farther, reveling in the ability to capture the most difficult of subjects in a way that is indistinguishable from a photo or living person. These dramatic skills often lead admirers to exclaim that the subjects look more real than reality, or at least more so than a photograph.

I’m mesmerized by this remarkable artistry. I can watch these artists perform their magic for hours on the web. And yet, because each of us has worked with play dough and paints, we know the basics of the process behind these pieces. We know that these images and forms have no more inner life than the oil or clay that comprise them. The highlights and shadows painted into the painting are not the product of three dimensionality or the light cast in the gallery. The light that illumined the artist’s subject is, in the painted medium, entirely illusionary.

Though they may be visually indistinguishable from a man or woman, passing the art equivalent of a Turing Test, we know that these portraits are not in the least the same kind of thing as what they portray. Whatever emotions we see in them is projected on them by us. Paint does not suffer. Stone does not breathe.

Dear God! How beauty varies in nature and art. In a woman the flesh must be like marble; in a statue the marble must be like flesh.

Victor Hugo, Victor Hugo’s Intellectual Autobiography: Being the Last of the Unpublished Works and Embodying the Author’s Ideas on Literature, Philosophy and Religion “Hyperrealistic Sculptures Blur the Line Between Clay and Flesh”

The incredible skills reaching the apex of imitation with paints on the canvas are, likewise, achieving stunningly convincing portraits on the screen via computer graphics.

Read Part II – “Moving Pixels“, and stay tuned for Part III – “Talking Boxes”, and Part IV – “The Composite”.

Note: I have included several works from artists to illustrate the distinctly visual nature of seductive optics. All living artists above are linked and the reader is encouraged to follow and explore their work.