Moving Pixels

Seductive Optics and Skeuomorphic Intelligence, Part II.Part II of a four part series. Read Part I, “Seductive Optics and Skeuomorphic Intelligence“.

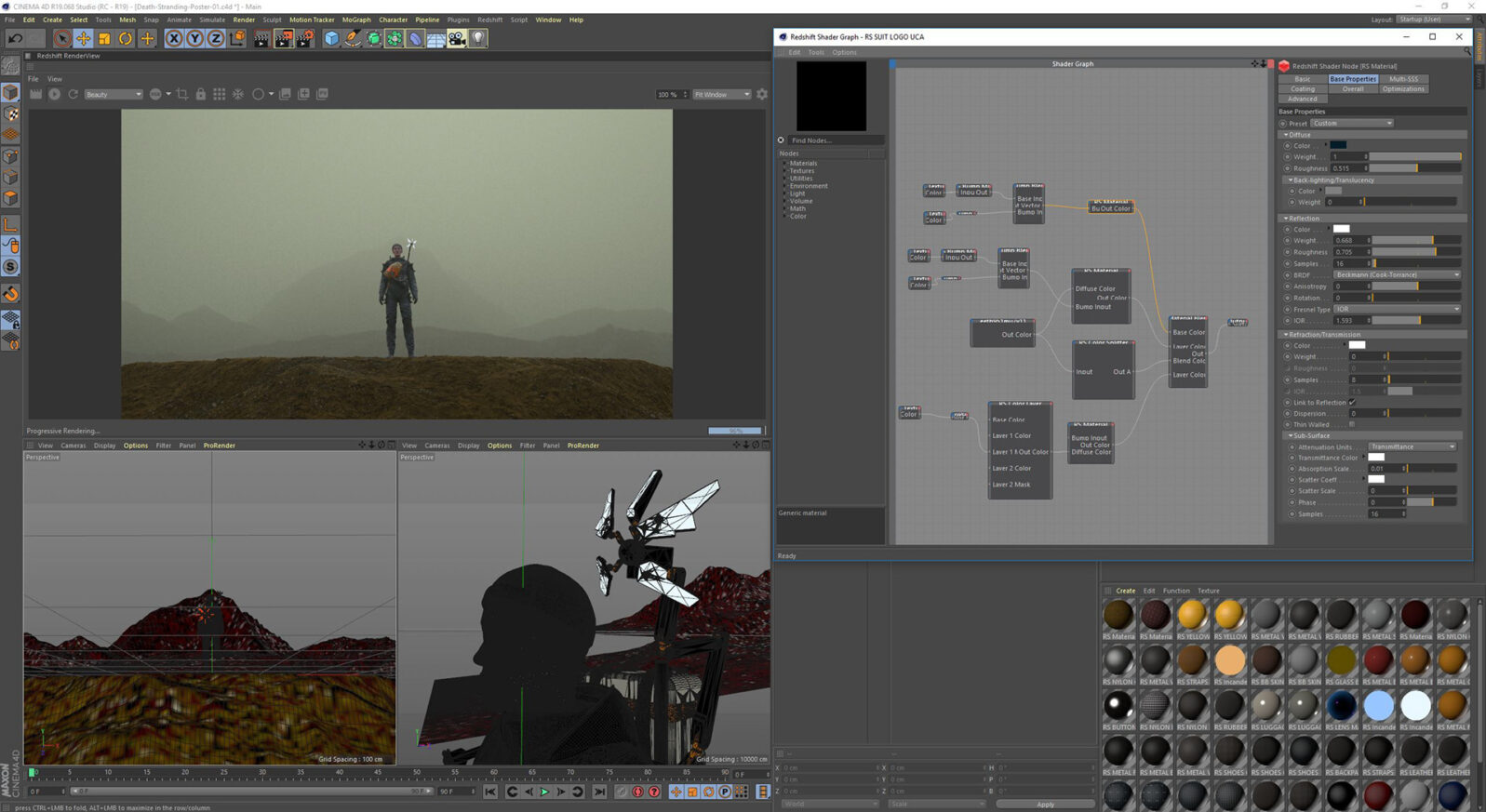

As with traditional art, computer animation has followed a similar trajectory toward realism. Early animations were as crude as rock carvings, limited as they were by relatively weak CPU’s, as yet undeveloped rendering engines, and a lack of digital artists. The monochromatic Space Invaders was endlessly playable, as were the whirling, 8-bit dervishes of Centipede and the bubble-gumless, three-dimensional spaces of Duke Nukem. But the graphics were a million pixels from virtual reality.

Now decades and countless iterations in, with enormous human capital and ingenuity invested into motion graphics and GPUs, the optics are indeed seductive, convincing, and engrossing. Head phones on and eyes glued to the screen, it’s easy to get lost in the sprawling world and epic narrative of Mass Effect, or to feel that you are attacking the Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen with an M1 Garand rifle, your rag-tag squad assisting. With each iteration, game developers make strides in simulating the unique recoil of each gun model, the aural pattern of explosions near versus far, the game physics of spilt blood and bent grass underfoot, and the fraying edges of a soldier’s ribbon bars, specific to rank and nation.

Bravo! Charlie! It’s amazing. It’s an adrenaline rush. And it’s all artifice. These animations are becoming ever more realistic, but not in the least bit more the kind of real thing which they represent.

In addition to cosmetic advances, motion capture technology has progressed by leaps and bounds. Painstaking attention to plotting our distinctive expressions and gaits has greatly increased the appearance of natural movement. Ever since Andy Serkis so convincingly gave life to Gollum, recordings of humans in motion have supplied the scaffolding for countless characters.

In animation … everything is fabricated. … Every moment. Every scratch and look. Everything is a discussion. There are no gifts. There are no happy accidents … It was useful having the live action performance reference. We’d pull them up in front of the animators and say, look at what’s happening here. Little twitches underneath the eyelid, little things that are involuntary became very important.

Gore Verbinski, “Rango Behind the Scenes: Breaking the Rules”

One of the joys as a viewer is having that dawning recognition of a familiar actor who has been reincarnated as Puss in Boots, Shrek the ogre, or Mator the tow truck. The idiosyncrasies and tics of the human originals are prized source material for the animators. So, Kristen Bell’s signature phrase — “Wait, what?” — and her habit of biting her lip is mirrored in Anna of Arendelle. Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson’s brow wave personalizes Maui. Although these beloved characters are singing and dancing and joking along, like Mona Lisa, the image is a mirror image. It has no life of its own.

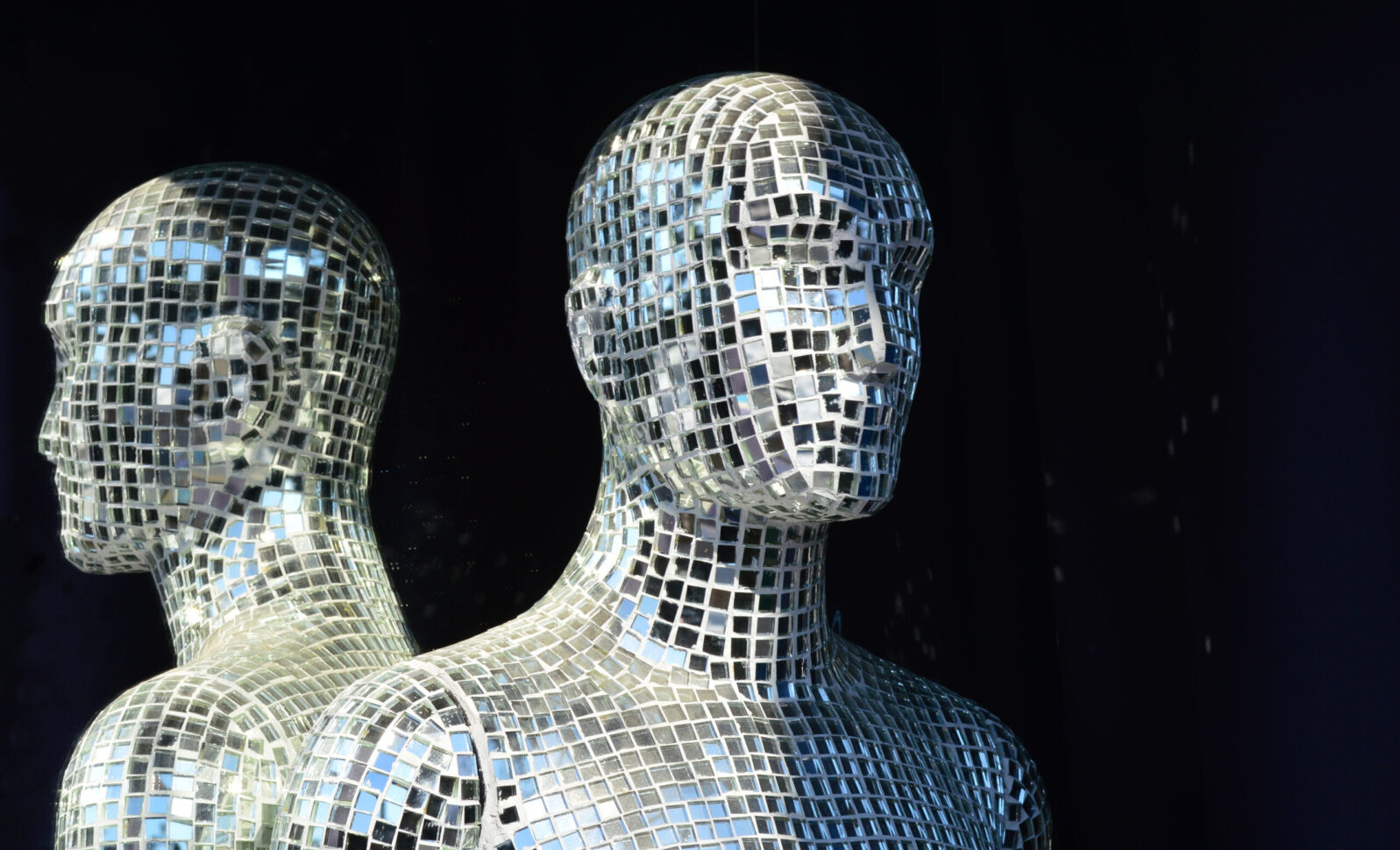

Though we are moved by these pixels on the screen, our digital allies and enemies breathe no breaths, make no sacrifices, feel no lonely deaths. Whether crying, dying, or respawning, they are as lifeless as a dead pixel and vacuous as a wireframe.

Because the textures that skin them and algorithms that animate them are more sophisticated, it is tempting to think that the ducking and evading Juvies, Pouncers, and Swarmaks of Gears of War are more intelligent than Pac Man’s nemeses: Blinky, Pinky, Inky and Clyde. One might think that whereas the ghosts that haunted Pac Man had a wisp of personality, the villainous grunts of a modern first-person shooter have a measure more. Surely, in some future game, they’ll reach self-realization. Game AI will continue on this trajectory and surpass human intelligence, just as Watson bested Kasparov. But the truth is, none of these avatars possess any inherent intelligence whatsoever. Every human instinct therein is an extension of a game developer’s forethought. The characters are thoughtless.

We’ve erected this elaborate system of gears and pulleys using electronic nodes. The number of these levers that we can fit on a circuit is mind boggling. At the push of a button and the tilt of a joystick, these systems are able to reenact remarkable routines that the human programmers have strung together. But as the less exhaustively routinized NPCs (Non-Playable Characters) in the game betray, if the programmer hasn’t yet written the routine, the character will be left kicking blindly into a wall.

Read Part III – “Talking Boxes“, and stay tuned for Part IV – “The Composite“.