C.S. Lewis and Science Fiction

Sci-fi can reveal that you don't necessarily need to visit Mars to find the bizarre and beautifulThe 20th-century intellectual, novelist, poet, and popular theologian C.S. Lewis was a rare bird. He spent most of his life embedded in the academic world, to which he contributed greatly, but was also a lover of fairy tales and the dystopian. His long-held affection for fantasy and science fiction led him to write some of the most popular fictional works in recent memory, most notably The Chronicles of Narnia and what’s commonly known as the “space trilogy,” though Lewis himself objected to the term “space” as an adequate descriptor of what he viewed as a vibrant and meaningful cosmos.

In a more obscure Lewis title, Of Other Worlds, Lewis writes of his appreciation for science fiction and what makes the genre unique. The anthology, edited by Walter Hooper, includes an essay directly titled “On Science Fiction.” Lewis was not a scientist and openly admitted that his own foray into science fiction involved little to no “technical” knowledge on his part. He respects the science fiction novel that pays its full due to the engineering complexity of modern technological marvels but writes that his own motivations went beyond the technical. He wasn’t in it to showcase his knowledge of rockets and the atmospheric pressure of Venus. A contemporary example of this kind of book is The Martian by Andy Weir, which details the survivalist account of a man stranded on Mars and his remarkable story of escape. The book often reads more like a scientific manual than a novel.

Sci-Fi’s Sub-Species

Lewis lists several other “sub-species” of science fiction, each with their particular powers and problems, until finally landing on the type he is most interested in. Here Lewis appeals to an ancient impulse in human beings that transcends and precedes the technological age in which so much science fiction is written. It is akin to the fairy tale, which seeks to unearth beauty, terror, or strangeness of the unknown through story. Lewis notes that the greater our scientific awareness of the cosmos, the farther out our tall tales must be located. The ancients, however, didn’t need to travel to Mars to be confronted by the alien. The dark forest a mile down the road was foreign enough to inspire their myths and legends. The ocean beyond the mountain was Mars enough. In any case, it’s the allure of the unknown and bizarre that inspires this kind of impulse, the one Lewis was interested in exploring himself. He writes,

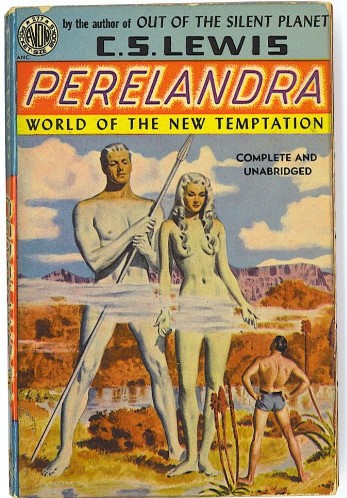

The most superficial appearance of plausibility—the merest sop to our critical intellect—will do. I am inclined to think that frankly supernatural methods are best. I took a hero once to Mars in a space-ship, but when I knew better I had angels convey him to Venus. Nor need the strange worlds, when we get there, be at all strictly tied to scientific probabilities. It is their wonder, or beauty, or suggestiveness that matter.

-C.S. Lewis, Library : On Science Fiction | Catholic Culture

The Wonder of the World

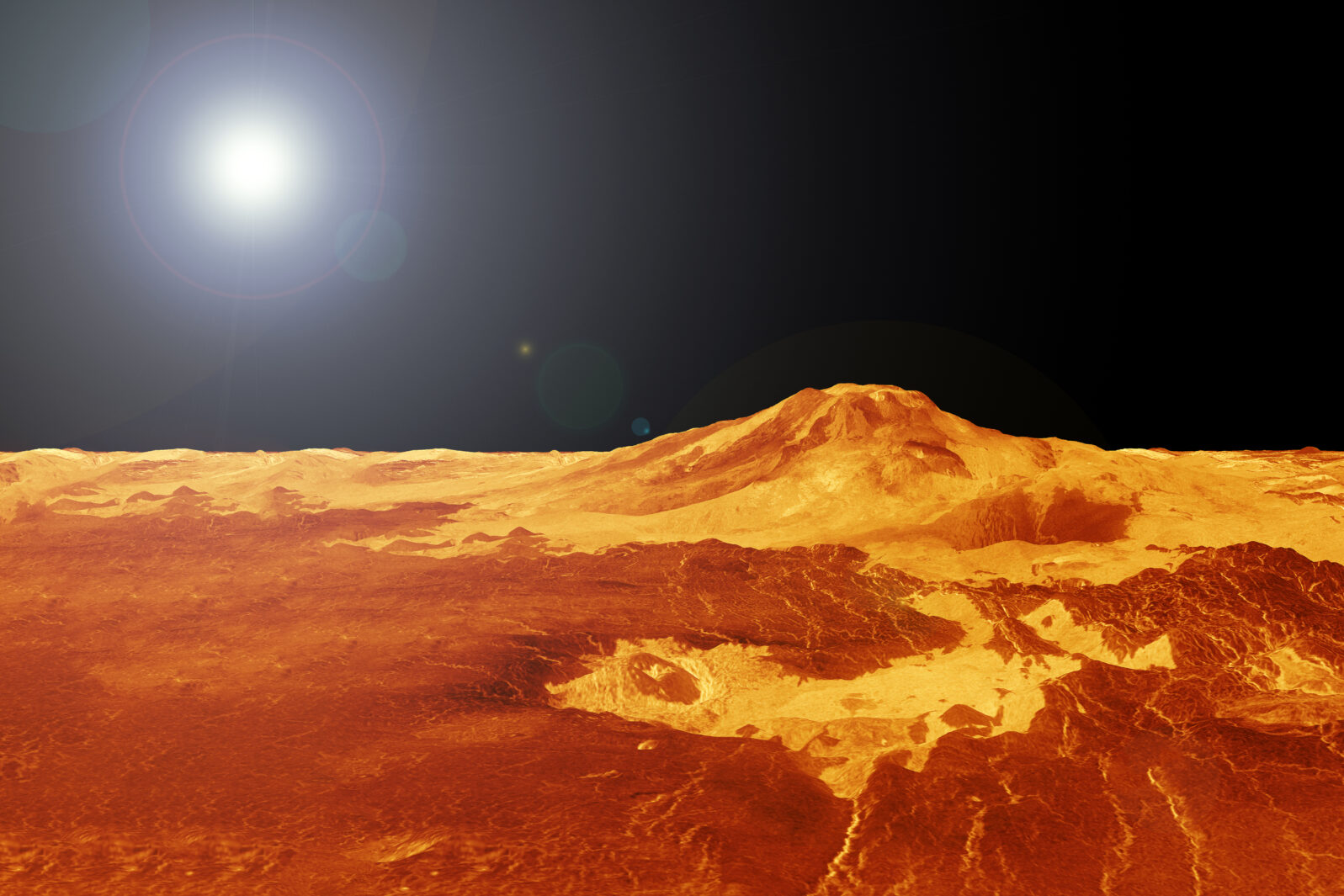

Lewis refers here to his novels Out of the Silent Planet and Perelandra. The former involves a spaceship while the latter is more unabashedly “mythic.” In a materialistic and purportedly scientific age, can we still experience this kind of wonder and beauty? Venus, after all, is an unlivable ball of lava. It is no longer a mystery covered in clouds. People have long gazed into the starry night in wonder, mapping out constellations and myths of their origins. Does scientific knowledge strip away the wonder? Since the science fiction and fantasy genres remain wildly popular in today’s culture, it seems that a reductionistic, materialistic worldview only amplifies and redirects our interest in the fantastic, the bizarre, and the mythic. The more secular we become, the more evident our longing for enchantment. Science fiction and fantasy are indirect ways that people push back against the disenchanted framework of materialism.

Lewis once said that George MacDonald’s Phantastes “baptized his imagination.” Phantastes was published with the subtitle “a faerie romance.” It was a book that, far from simply giving him a momentary escape from the “real” world, made his ordinary surroundings abruptly pop with beauty, meaning, and purpose. Perhaps that’s what the mythic and imaginative works of science fiction can do: make us marvel anew at the bizarre, the wondrous, and the astounding realities right beneath our noses. There’s a lot more yet to discover, after all. Sci-fi can be a way to speculate future dystopias, act as prophetic warnings, and detail the technicalities of a machine-ridden world. It can also renew our sense of the bizarre and beautiful, which for Lewis, was much closer to us than we often assume.