Earliest Brain Found — From Over Half a Billion Years Ago

No one was expecting the Cardiodictyon fossil to have a brainA surprising find for evolutionary neuroscientists is that a tiny life form that lived more than half a billion years ago had a brain. Creatures like Cardiodictyon were not supposed to have had brains:

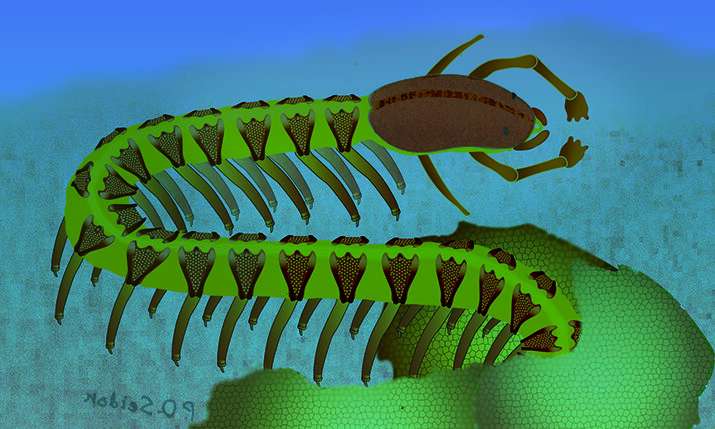

A study published in Science—led by Nicholas Strausfeld, a Regents Professor in the University of Arizona Department of Neuroscience, and Frank Hirth, a reader of evolutionary neuroscience at King’s College London—provides the first detailed description of Cardiodictyon catenulum, a wormlike animal preserved in rocks in China’s southern Yunnan province. Measuring barely half an inch (less than 1.5 centimeters) long and initially discovered in 1984, the fossil had hidden a crucial secret until now: a delicately preserved nervous system, including a brain.

University of Arizona, “525-million-year-old fossil defies textbook explanation for brain evolution” at Phys.org (November 25, 2022) The papers (here and here require a fee or subscription.

It’s the earliest brain found so far and here’s a remarkable fact:

Cardiodictyon belonged to an extinct group of animals known as armored lobopodians, which were abundant early during a period known as the Cambrian, when virtually all major animal lineages appeared over an extremely short time between 540 million and 500 million years ago. Lobopodians likely moved about on the sea floor using multiple pairs of soft, stubby legs that lacked the joints of their descendants, the euarthropods—Greek for “real jointed foot.”

University of Arizona, “525-million-year-old fossil defies textbook explanation for brain evolution” at Phys.org (November 25, 2022)

So the brain — perhaps the most remarkable known organ — appeared rather suddenly in the Cambrian, as opposed to having evolved over a long period of time much later.

Researchers had assumed that the entire body of Cardiodictyon was segmented but it turns out that the head and brain are not.

Another (unrelated) surprise finding in recent years is the intelligence of octopuses and some (but not all) of their relatives. Invertebrates were not supposed to be intelligent, relative to vertebrates — and only a few of them are. But just how only those few got to be intelligent is unclear.

But science would hardly be a much fun without a few surprises and complexities.

You may also wish to read: Octopuses get emotional about pain, research suggests. The smartest of invertebrates, the octopus, once again prompts us to rethink what we believe to be the origin of intelligence. The brainy cephalopods behaved about the same as lab rats under similar conditions, raising both neuroscience and ethical issues.