What Motivates Chimpanzee Experts Anyway?

Is it the welfare of primates or is it “politics by other means”?A review by animal historian Brigid Prial of a recent book in which chimpanzee experts reflect on their work tells us a good deal about the chimpanzee expert world.

The reviewer is also the author of “Primatology is Politics by Other Means” from which we learn:

“Adam and Eve, Robinson Crusoe and Man Friday, Tarzan and Jane: these are the figures who tell white western people about the origins and foundations of sociality. The stories make claims about “human” nature, “human” society. Western stories take the high ground from which man — impregnable, potent, and endowed with a keen vision of the whole — can survey the field. The sightings generate the aesthetic-political dialectic of contemplation/exploitation, the distorting mirror twins so deeply embedded in the history of science.

Wait. Isn’t it a fact that humans do have a keen “vision of the whole” and that chimpanzees do not? And cannot?

Yes. Humans are concerned with chimpanzee welfare and chimpanzees are not concerned with human welfare. All the theorizing and politicking in the world will not change the difference that the human mind makes.

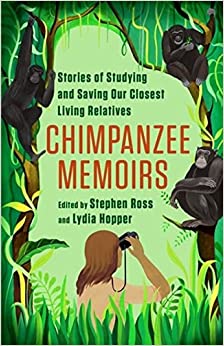

From the h-net review: Chimpanzee Memoirs: Stories of Studying and Saving Our Closest Living Relatives (2022) is, we are told,

Several chapters, notably by established primatologists Goodall, Richard Wrangham, and Christopher Boesch, discuss aspects of their work that have been viewed as controversial, perceived as challenging orthodoxy, or publicly misconstrued. Boesch describes how his observations of cooperation and teaching behaviors in chimpanzees at Taï Forest in Côte D’Ivoire were dismissed by anthropologists and psychologists who privilege laboratory data and believe in “human superiority” (p. 88). Goodall and Wrangham both noted backlash they had received regarding their findings about aggression and violence in chimpanzees, controversies that are examined extensively by Erika Lorraine Milam in her book Creatures of Cain: The Hunt for Human Nature in Cold War America (2019). Supervisors told Goodall that publishing her claims in the 1970s would lend credence to those who argued that war was an inevitability, while Wrangham received similar resistance to his admittedly provocatively titled book Demonic Males: Apes and the Origins of Human Violence (1997). Many authors also describe frustration with the way their research has become sensationalized or stripped of nuance in the media. Elizabeth Lonsdorf was particularly disappointed to see her work lampooned on a “men’s rights” website. For historians of science, these chapters provide insight into how the science of animal behavior is mined for answers to contentious social questions of gender and violence.

But haven’t these academics made their own field ridiculous already? If they want to claim that chimpanzees, who lack abstract thinking, can teach us a lot about human beings, who have it, they have just plain set themselves up.

In the human world, a guy who behaves like a chimpanzee typically ends up in jail. But why are we even discussing this (“gender and violence”)?

Then we are told, “Animal studies scholars have argued that academic work purporting to be about animals often recenters the human and fails to engage with the animals themselves.”

But what are we talking about here? It is not possible for a human to interact with an animal (cat, dog, or chimpanzee) from a position that does not begin with the human.

The book doubtless provides useful practical information about chimpanzees but we should ask whether the overall — enthusiastically endorsed — approach in the chimpanzee industry (chimps r us!) is especially useful, apart from essential conservation efforts.

You may also wish to read: But, in the end, did the chimpanzee really talk? A recent article in the Smithsonian Magazine sheds light on the motivations behind the need to see bonobos as something like an oppressed people, rather than apes in need of protection.

and

The real reason why only human beings speak. Language is a tool for abstract thinking—a necessary tool for abstraction—and humans are the only animals who think abstractly