The Philosopher’s Zombie Still Walks and Physics Can’t Explain It

Various thinkers try to show that the zombie does not exist because consciousness is either just brain wiring or an illusion, maybe bothCanadian science journalist Dan Falk tells us, the philosopher’s zombie thought experiment, “flawed as it is,” demonstrates that physics alone can’t explain consciousness. Not that many physicists haven’t tried. But first, what is the philosopher’s zombie (sometimes called the p-zombie)?:

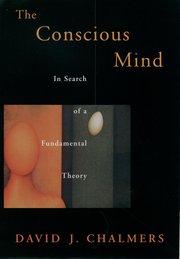

The experiment features an imagined creature exactly like you or me, but with a crucial ingredient – consciousness – missing. Though versions of the argument go back many decades, its current version was stated most explicitly by Chalmers. In his book The Conscious Mind (1996), he invites the reader to consider his zombie twin, a creature who is ‘molecule for molecule identical to me’ but who ‘lacks conscious experience entirely’.”

He does everything he is supposed to do but experiences nothing inside.

In step two, Chalmers argues that if you can conceive of the zombie, then zombies are possible. And finally, step three: if zombies are possible, then physics, by itself, isn’t up to the job of explaining minds. This last step is worth examining more closely. Physicalists argue that bits of matter, moving about in accordance with the laws of physics, explain everything, including the workings of the brain and, with it, the mind. Proponents of the zombie argument counter that this isn’t enough: they argue that we can have all of those bits of matter in motion, and yet not have consciousness.

Dan Falk, “The philosopher’s zombie” at Aeon (February 4, 2022)

Cosmopsychist Philip Goff offers a similar argument in Galileo’s Error: Foundations for a New Science of Consciousness.

Falk assembles a number of experts who dispute the idea that the zombie shows that consciousness is not strictly physical. He starts by offering an objection himself:

To begin with, are zombies in fact logically possible? If the zombie is our exact physical duplicate, one might argue, then it will be conscious by necessity. To turn it around: it may be impossible for a being to have all the physical properties that a regular person has, and yet lack consciousness.

Dan Falk, “The philosopher’s zombie” at Aeon (February 4, 2022)

That approach would, of course, imply that consciousness automatically arises from the complexity of the human brain. One might argue that; it is unclear how to demonstrate it.

A quick summary of other dissenting views:

● University of Sheffield philosopher Keith Frankish, who thinks that consciousness is an illusion, argues that if we could really understand everything that the brain’s 80 billion neurons were doing, we “wouldn’t feel that something was left out.” We will certainly have to decide whether to take his word for that as we cannot really imagine all those connections. His view is a form of promissory materialism (if you could really understand, you would be a physicalist and think that absolutely everything is physical).

● Cosmologist Sean Carroll offers an example involving time travel and the question of whether the zombie is conceivable:

If you went back 10,000 years and explained to someone what a prime number is, and asked: ‘Is it conceivable to you that there’s a largest prime number?’ Well, they might say “yes”; as far as they can conceive, there could be a largest prime number. And then you can explain to them, no, there’s a very simple mathematical proof that there can’t be a largest prime number. And they go: “Oh, I was wrong – it’s not conceivable.”

Dan Falk, “The philosopher’s zombie” at Aeon (February 4, 2022)

But wait. The largest prime number is conceivable. It just can’t exist in an infinite series. Mathematician Gregory Chaitin, best known for Chaitin’s unknowable number, also talks about the smallest uninteresting number — which turns out not to exist, for reasons of logic. Note that both the unknowable number (which exists but can’t be known) and the smallest uninteresting number (which doesn’t exist) are quite conceivable. Dr. Carroll is not giving the human imagination nearly enough credit.

● Philosopher Massimo Pigliucci tells us that “once-conceivable things often get demoted to the realm of the inconceivable” and has written that ‘conceivability establishes nothing’.”

Well, that depends. Everything in the world of thought starts as a concept. Human consciousness is called the “Hard Problem because it is inconceivable or barely conceivable from a physicalist viewpoint. It cries out to be explained away as an illusion, a misunderstanding, or a glitch. But decades pass and it never is.

What’s inconceivable is a function of our core beliefs. But would any of these thinkers make these arguments if they were not conscious themselves? The zombie would perhaps not initiate the arguments but might parrot them effectively. That might make an interesting additional thought experiment.

Falk quotes physicist Brian Greene on the ensuing problem:

“Physicalists who aren’t swayed by the zombie argument are left pondering the question we began with: how, in a purely physical world, do minds arise? In Until the End of Time, Greene – as ardent a physicalist as they come – writes that the existence of minds represents ‘a critical gap in the scientific narrative … We lack a conclusive account of how consciousness manifests a private world of sights and sounds and sensations.’”

Dan Falk, “The philosopher’s zombie” at Aeon (February 4, 2022)

In short, for Greene, an account of consciousness seems to mean explaining consciousness away.

For now, Frankish and Carroll hope to make the Hard Problem disappear by seeing consciousness as a process rather than a thing. Falk cites Carroll,

Carroll believes the hard problem will eventually fade away – that is, centuries from now (decades if we’re lucky), people will no longer speak of it as a great mystery. Eventually, we’ll have learned enough about the workings of brains and their billions of neurons, says Carroll, that we’ll just say “Well, this is what happens when people have conscious experiences” – adding: “And then the whole problem will just kind of go away.”

Dan Falk, “The philosopher’s zombie” at Aeon (February 4, 2022)

Alternatively, physicalism will largely cease to be entertained.

Curiously, consciousness is the subject of a famous 1998 wager between Christof Koch (yes) and David Chalmers (no) that wager that, within 25 years, the signature of consciousness would be found in the brain. It has only two years to run and the Eureka! moment is indefinitely postponed.

Falk himself takes a neutral position:

The zombie argument provokes for the same reason that the larger puzzle of consciousness provokes: it forces us to confront problems that stymied everyone from the ancient Greeks to Descartes and Galileo. Even the most hardened of the hardcore physicalists admit that the puzzle of consciousness is, well, puzzling. The zombie argument, flawed as it is, deserves credit for helping to bring difficult questions into sharp relief, even if it’s not the knock-down argument against physicalism that its proponents imagine it to be.

Dan Falk, “The philosopher’s zombie” at Aeon (February 4, 2022)

The zombie argument does what it is supposed to do: It shows that consciousness, the motivating force in our lives, can’t really be a material thing.

You may also wish to read:

Neuroscientist Michael Graziano should meet the philosopher’s zombie. To understand consciousness, we need to establish what it is not before we create any more new theories. A p-zombie (a philosopher’s thought experiment) behaves exactly like a human being but has no first-person (subjective) experience. The meat robot violates no physical principles. Yet we KNOW we are not p-zombies. Think what that means. (Michael Egnor)

and

Neurosurgeon explains why you are not a zombie. Michael Egnor explains to podcaster Lucas Skrobot that our minds must necessarily transcend our materials, so we can’t be zombies. (Michael Egnor)