Our Beliefs Change Us But the Core Is What Matters

A doctor who studies mystical experiences reflects on what ties life-changing beliefs togetherDoes what we believe matter? Last week, we noted that in podcast #165 at Mind Matters News (December 16, 2021), neurosurgeon Michael Egnor continued a discussion with neurologist Andrew Newberg on what we know about spirituality and the brain. This week, they talked about how we connect with spirituality in different ways.

Dr. Newberg has published a number of books on the topic, including How God Changes Your Brain (2009) and Why God won’t go away (2008).

This portion begins at approximately 13:13 min. Show Notes, and a partial transcript follow:

Andrew Newberg: When somebody conceives of a soul as immaterial, what does that mean? How does a brain understand that? And how do we engage that in an idea? Part of it is, is how does the brain actually… what is the brain doing when it’s thinking about an immaterial soul?… Could we go to a church, for example, and ask 100 people, what do they think about the soul? And how would they describe it or define it or what terms would they use. And see, does everybody say it’s immaterial? Does everybody say it doesn’t interact with the brain? Do people say it does …

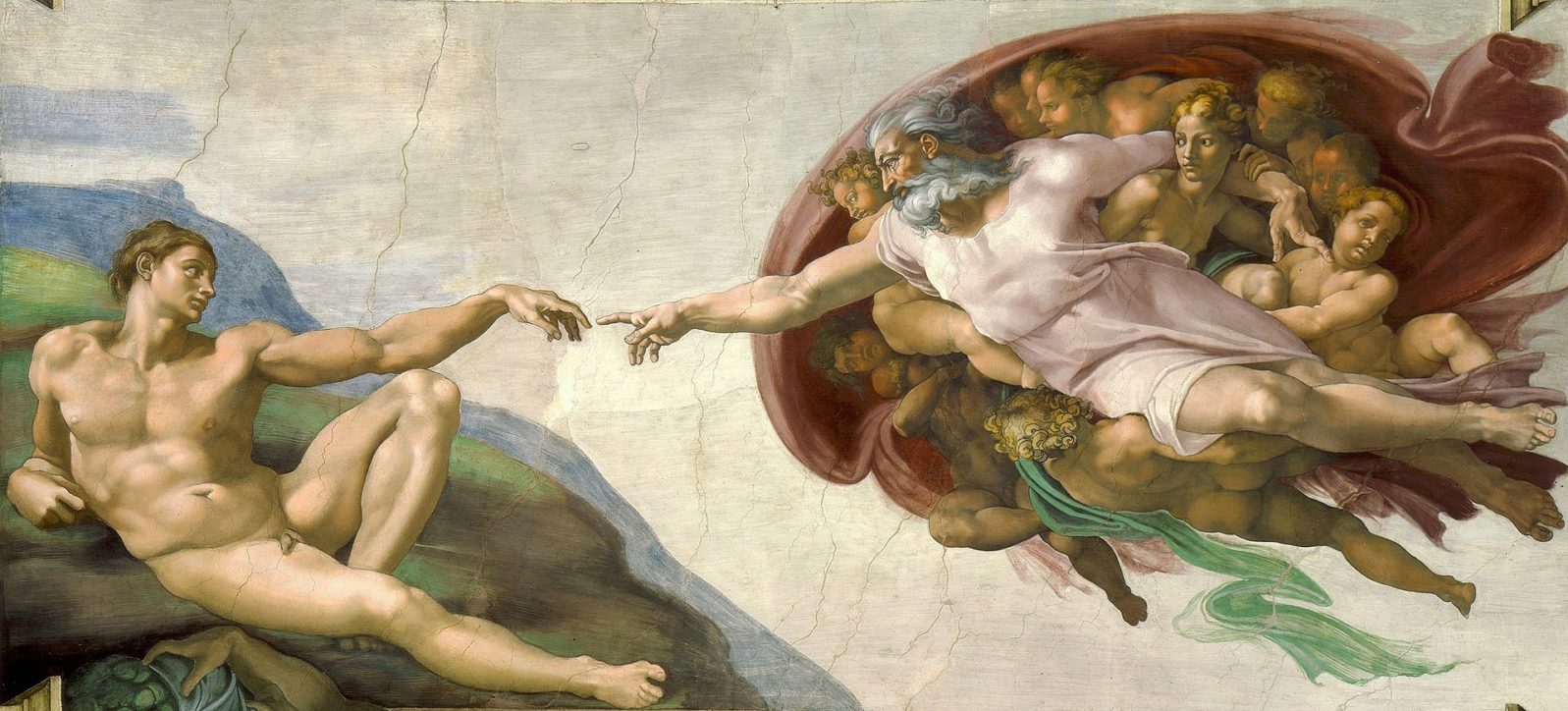

We did a study for one of our books, How God Changes Your Brain, where we asked people to draw a picture of God. And we said… what does God look like? What pops into your mind? And it was fascinating to see what people would draw. And sometimes people draw a very anthropomorphized… the Sistine Chapel concept of God. As a, sort of, old man with a beard and flowing hair. Other people drew very abstract ideas, nature. And fascinatingly, some people left it blank, because they said God is undrawable. And there’s no way for me to actually draw God.

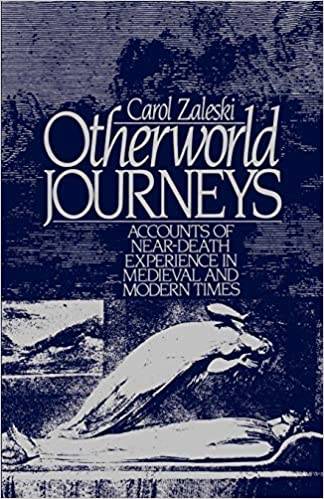

Michael Egnor: There’s a fantastic book called Otherworld Journeys by Carol Zaleski. I couldn’t put it down. It absolutely fascinated me.

And what she points out that I think is so intriguing, is that throughout human history, there have been these spiritual experiences, in all cultures, in all eras, and they seem to have significant commonalities. But the actual content of the experience seems to be determined significantly by your culture, by the world that you’re living in. That a person living in our culture would have a different experience of God than a person living in the Middle Ages or a person living in ancient Egypt or a person living in the Far East. … the experiences that people are having are transcendent and they can’t be expressed in their actual form. We can only express them through things that we know in our daily lives. And that fascinates me.

That raises a whole other area which is, to me, very important in the field of neurotheology. She was focusing a lot, as you mentioned, actually on near death experiences. If somebody has a near death experience and they see a being, somebody might… a Christian may call it Jesus. And a Muslim may call it Allah. And a Hindu may call it Vishnu or something like that. But so then the question becomes is, did they all see the same thing that they are, as you said, they’re describing it the best they can based on their prevailing belief system. Or did they actually fundamentally see something different?

And in a similar context, we did this whole online survey of people’s most intense spiritual experiences. And some people would say, I felt God. Some people said, I felt a force. Some people felt love. Some people felt awe. Again, are they the same experience interpreted differently, or are they actually different experiences?

I think that by exploring the descriptions of these experiences, maybe if we can somehow get to something that’s going on in the brain and trying to understand that, we can see where similarities are and the differences. Maybe everyone perceives a being, but they just call it different things. But the being is the universal trait.

… one of the common experiences in these mystical experiences is the feeling of oneness and connectedness with God, with the universe. So does everybody already have that experience? And if so, what do they feel connected to? And which are the more perennialist, universal characteristics of these experiences, and what are the ones which are unique? And how do we understand those unique characteristics? So, yeah. Really, really fascinating. And thinking about, again, what’s really happening in the experience? What is happening in the person’s consciousness and mind? What’s happening in their brain? And see what we can do about trying to understand the nature of those experiences as best as possible.

And of course, again, to me, one of the most fascinating things about all of these experiences is that… and we wrote an article on this. That people describe them as being more fundamentally real than our everyday reality experience. And of course, for the other listeners, we all have that. Because no matter how real a dream feels when we’re asleep, when we wake up, we say, oh, that was just a dream. We immediately relegate it to an inferior perspective of reality. But that’s exactly what happens in the context of people having these mystical experiences, which is that the everyday reality then becomes inferior. And I don’t mean that quite so hierarchically, but that it’s not as real as these profound experiences.

And of course, again, what does that mean? Does that mean that they really have achieved a connection? That their brain has connected to a different plane, a different way of looking at the world that it hasn’t been able to do before? Or is it just a manifestation of the brain? I mean, it’s really quite fascinating.

Next: What can doctors tell us tell us about near-death and other mystical experiences?

Earlier segments:

Meet a doctor who thinks spirituality isn’t just all in your head. Can science study what you are doing when you pray? Andrew Newberg does and he says the effects are real. New neuroscience techniques can demonstrate that the effects are real, according to Andrew Newberg’s studies

and

Science is discovering that mystical experiences are real When we contemplate, says neurologist Andrew Newberg, who studies such experiences, the frontal and parietal lobes of our brains quiet down. Brain areas that help us “do things” or express our “selves” go much quieter so, for once, we can just listen.