Why Does “Evolution Theory” Trivialize Everything It Touches?

A pair of evolutionary anthropologists try their hand at dealing with existential grief, anxiety, and depressionA couple of evolutionary anthropologists tried their hand recently at illuminating the depths of human anxiety. They started by getting one thing clear right away:

Researchers in our field are trained to think about humans in the same way that we think about chimpanzees, macaques and any other animal on the planet. We recognise that humans, like all other species, evolved in environments that posed many challenges, such as predation, starvation and disease. As such, human psychology is well-adapted to meet these challenges.

Kristen Syme and Edward H. Hagen, “Most anguish isn’t an illness but an evolved response to adversity” at Psyche (September 29, 2020)

So humans are just like other animals. Syme and Hagen oppose treating “the common mental afflictions of depression and anxiety as illnesses” when, from their perspective, they are adaptations for evolutionary survival.

Okay, so what’s the big message that everyone else has been missing?

First, evolution has not shaped humans to be perpetually happy or free of pain. On the contrary, we’ve evolved pain neural circuits because our ancestors who experienced physical pain in response to environmental threats were better able to escape or mitigate those threats, out-reproducing their peers who didn’t experience pain. We evolved to experience suffering as much as we evolved to experience wellbeing.

Kristen Syme and Edward H. Hagen, “Most anguish isn’t an illness but an evolved response to adversity” at Psyche (September 29, 2020)

What? Do we have any reason to believe that some of our ancestors were “peers who didn’t experience pain”? What could these peers have been like? Ancient literature is pretty clear on the point that the human plight is universal. As many old stories tell us, first the Creation of man, then the Fall. But Syme and Hagen move on:

From an evolutionary perspective, it is logical that people today display strong negative emotional responses to forms of adversity that were common during our evolutionary history, such as status loss, death of social partners and physical attack. To survive and reproduce and pass on their genes, organisms must respond adaptively to dangerous environments, often by escaping them and learning to avoid them. In many animals, it is emotions that guide behaviours. Fear, anxiety, sadness and low mood are forms of psychological pain that probably serve functions that are analogous to physical pain – informing the organism that it is experiencing harm, helping it escape or mitigate harm, and stimulating it to learn to avoid similar harms. Psychological pain, like physical pain, probably evolved by natural selection, and in many or most cases is therefore not a disease.

Kristen Syme and Edward H. Hagen, “Most anguish isn’t an illness but an evolved response to adversity” at Psyche (September 29, 2020)

Their approach is in the unique position of making no sense at all.

If we were the first human beings who had ever existed and had suddenly popped into existence a half century ago, we would likely react about the same way to the death of a loved one. We grieve deeply because we rationally understand what is happening (“I will never see Rose again”), not because we evolved one way or another. If Syme and Hagen wish to explain exactly how humans came to consciously use reason in apprehending our environment, they will be the first to do so. Be warned: The Hard Problem of consciousness is hard indeed.

Syme and Hagen fear that they are misunderstood by the mental health professionals who think that serious depression is a disorder rather than an adaptation: “Disease model advocates argue that their approach reduces stigma by showing that the person is not to blame and by conveying the seriousness of their condition; they see alternative models as placing blame on the sufferer.”

Probably. But it’s unclear that most mental health professionals treat grief and anxiety as a disease unless it is harming physical and mental health and relationships, and then they really must see it that way. Issues about how and why it “evolved” wouldn’t matter much in the medical context.

In the same vein, Syme and Hagen go on to inform us, “… what the disease perspective has done is distract us from talking about the source of most mental anguish: adversity, often caused by conflicts with powerful or valuable others, such as employers, mates and kin.”

What? Are they really saying that no counselor has ever paid close attention to the effects of work and relationship issues in triggering serious depression?

The actual difference between typical mental health counsellors and evolutionary anthropologists is that the former do not treat mental health issues as if everyone involved were an animal, lacking reason and moral choice. But the evolutionary anthropologist, at least in Syme and Hagen’s account of their discipline, is obliged to do so. Evolutionary anthropology seems to mean never having to say that reason and moral choice matter.

Here’s a giveaway line: “Our ancestral lineage has grappled with adversity since before the dawn of Homo sapiens.” Yes, and doubtless the trilobite grappled with adversity too. But it wasn’t until the “dawn of Homo sapiens” that self-awareness made unhappiness a philosophical issue (As in, “Why are things the way they are?”)

Reducing the sufferer to the status of an animal (“chimpanzees, macaques…”) means that the evolutionary anthropologist contributes little of value to the discussion of human anguish. We are left instead with awful, crashing platitudes:

But the reality is that some adversity is an unavoidable part of human life, caused by intractable conflicts of interest. If one person abandons her romantic partner for another one, for example, this is to her benefit and her ex-partner’s detriment. There is no way, at least in the short term, to make that better for the abandoned partner; nor is there a practical or fair way to prevent such strife from ever occurring.

Kristen Syme and Edward H. Hagen, “Most anguish isn’t an illness but an evolved response to adversity” at Psyche (September 29, 2020)

Yes. But so? Serious moral philosophers start here, they don’t end here. Syme and Hagen end here because this is all they have. There is no upper floor to their reasoning. It’s all about people as if we were animals and life as if explicitly Darwinian evolution decided everything. And neither of those propositions happens to be true.

They end, predictably, with a call to address social injustices:

Just because psychological pain is unpleasant to the self and others, that doesn’t make it a disease, and we shouldn’t seek in the first instance to blunt it with drugs or other medical interventions. Instead, we should look to the social roots of adversity – to inequities, injustices and individual selfishness – and consider if and how we can harness mental anguish to help change ourselves, and other people’s lives, for the better.

Kristen Syme and Edward H. Hagen, “Most anguish isn’t an illness but an evolved response to adversity” at Psyche (September 29, 2020)

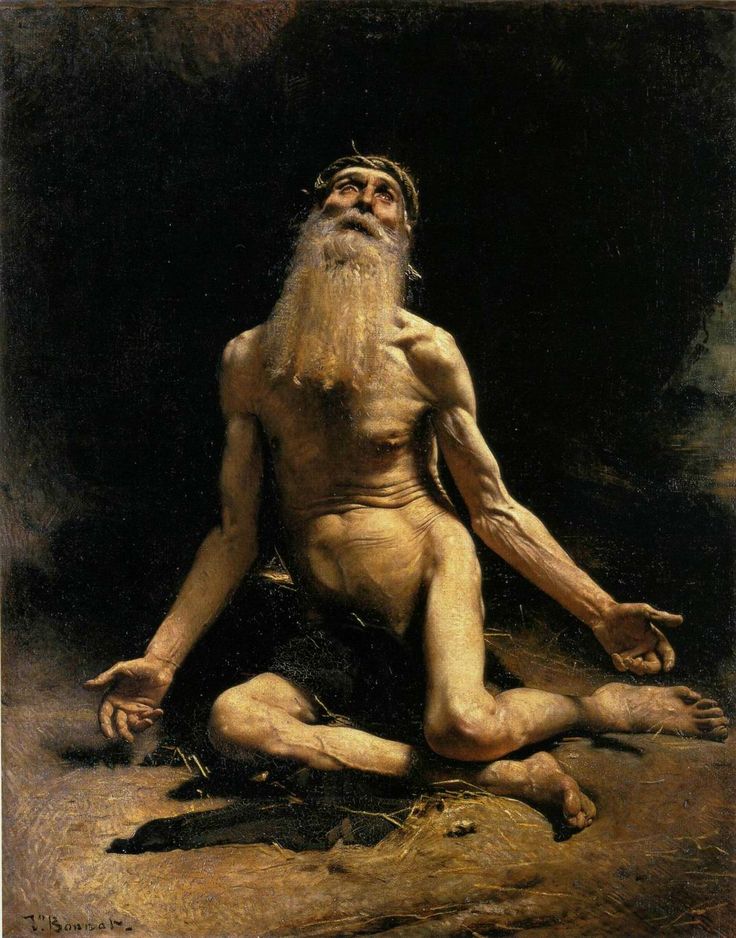

But Syme and Hagen’s no-upper-storey perspective exempts them from the hard task that others must face of determining which social reforms would really help. Or, for that matter, whether any reforms offer a longterm “cure” for mental anguish in a world where all of us are mortal and philosophy means learning how to die (a perspective not granted to animals). Note: The 1880 painting above by Léon Bonnat depicts Job, a Biblical figure known for the severity of his tribulations and his struggles to understand them.

One turns with relief to traditional sources of comfort to those in anguish, for example, the Psalms:

Lord, how many are my foes!

How many rise up against me!

Many are saying of me,

“God will not deliver him.”

Suddenly, one is back in the real, human world of reason, philosophy, theology, moral choice, relationships, and suffering—and far from the thundering herd of platitudes (“psychological pain is unpleasant to the self and others”) and vague cliches (“social roots of adversity”).

Probably, any perspective that starts with the view that humans are merely evolved animals will show the defects Syme and Hagen’s essay exhibits, leading to empty prescriptions rather than insight or inspiration. But one cannot expect those in the grip of such a point of view to even be aware of that, let alone understand it as a fundamental problem.

You may also enjoy:

The real reason why only human beings speak. Language is a tool for abstract thinking—a necessary tool for abstraction—and humans are the only animals who think abstractly.

and

Does brain stimulation research challenge free will? If we can be forced to want something, is the will still free?