Interview With a Woman (or Women) Formerly Called Susan Blackmore

A professor of psychology argues that there is no continuity between our present selves and our past selvesMuch of modern philosophy of mind is a compendium of New Age gibberish. An exemplar of this mess is Susan Blackmore, a Visiting Professor (Psychology) at the University of Plymouth. She is an atheist, a “skeptic,” and a prolific author. When she was interviewed in 2016 about her philosophy of mind, remarkably, in addition to the usual atheist denial of immortality of the soul and of free will, she denied personal continuity over time.

How does Blackmore account for the doggedly persistent sense we have of personal continuity? “Parallel processing” is her explanation. Blackmore points out that there are many brain pathways that are active simultaneously when we perceive, think, and act.

What does that have to do with personal continuity? After all, my car has many parts that do different things simultaneously. But I am quite sure that the car I drove home from work today is the same car I drove to work this morning. Why would parallel acting parts or loss and replacement of matter over time be inconsistent with continuity?

Blackmore seems unaware of the history of this ancient metaphysical problem, called the problem of change. It was the central problem tackled by the pre-Socratic philosophers. How do we explain change? It would seem that everything is change because everything in nature changes with every moment in some respect.

But then it would make more sense to say that the old thing disappeared and the new thing appeared. But in that case, the only way that a thing can come to exist is by coming from that which didn’t exist. And from nothing, nothing can come. That implies that change is an illusion. Either everything is change or nothing is change.

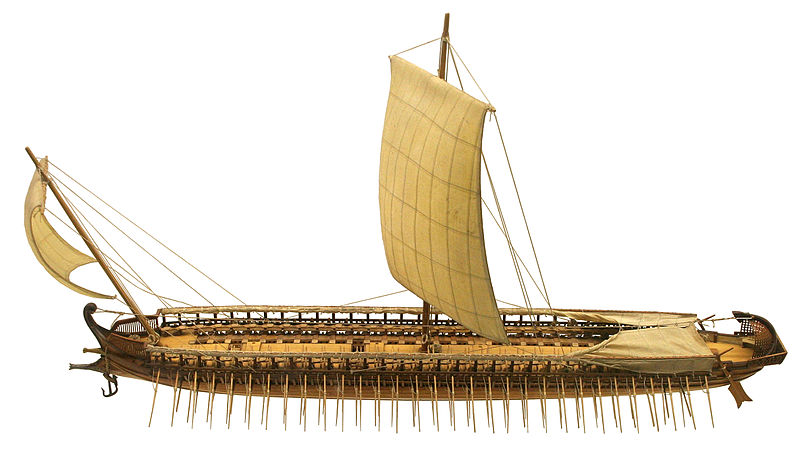

Consider a classic metaphysical paradox: the ship of Theseus. Periodically, a ship undergoes repairs. Parts are gradually replaced until, finally, every bit of matter in the ship has been changed. Is it the same ship? If yes, then how can it be the same ship if not a bit of the matter that was in the original ship is still there? Is it a different ship? It looks and functions exactly the same and common sense tells us it’s the same ship. And if it is a different ship, exactly when did it become different? When the first wooden plank was replaced, or the last? Why choose either?

You can make the question even more devilish. Imagine that you replace wood from the ship with wood from your house and replace the wood from your house with wood from the ship. At the end, is the ship now your house and your house now your ship? Do you live in your ship and sail your house?

Aristotle answered this paradox to the satisfaction of the ages (excepting Blackmore, apparently) with his theory of form, involving substantial form, accidental form, and matter. A thing’s form makes it what it is is. Form is the intelligible principle of a thing, roughly, its organizational pattern.

However, there are two kinds of form to consider. Substantial form makes a thing what it is. A ship’s boat-like shape is part of its substantial form because if it isn’t boat-shaped, it isn’t really a ship. Accidental form is an aspect of a thing that can change without changing what the thing is. For example, the ship may be painted red. Red is an accidental form because the ship can be repainted blue and still be a ship.

During change, accidental form changes while substantial form stays the same. Matter carries form, so when your ship is gradually replaced with wood from your house, and vice versa, the matter exchanged carries accidental form while the substantial forms, the patterns, of the ship and the house both persist.

Thus, your ship and your house persist through the change, even though they have switched matter. Change entails both persistence of substantial form and replacement of accidental form.

What about personal continuity over time? The human soul, of which the mind is one of several powers, is the form of the body. Accidental forms of the body—skin cells, height, weight, hair color, memories, perceptions etc. change, but the substantial form—the human soul—remains the same. That’s what persists in a human being despite continual change in mental states and physical matter.

Aristotle’s metaphysics and psychology renders Blackmore’s problem of continuity moot. Blackmore herself persists through time, despite mental and physical changes, because her soul, which is a substantial form, persists despite changes in molecules and memories.

But you need not pore over Aristotle’s De Anima to figure out that Blackmore’s denial of personal continuity is rubbish. After all, if Blackmore is not the same person now that she was a moment ago, then it makes no sense to call the YouTube video above an interview with Susan Blackmore. Perhaps it should be called interviews with Susan Blackmores or interviews with countless women, one of whom was Susan Blackmore. Or interviews with women formerly known as Susan Blackmore.

If Blackmore is not the same person moment to moment, then her publishers are sending the royalty checks from her books to a long line of impostors. When she goes to the bank to cash checks, she’ll be withdrawing from another woman’s account. Of course, if someone called the cops (“Hello 911, there’s a different woman trying to withdraw from Susan Blackmore’s bank account!”), Blackmore could just claim that she (they) were continuously different persons, so the woman attempting the financial fraud against the previous woman isn’t her contemporary self anyway…

Of course, if Blackmore said this type of thing in an everyday context, she might end up a beneficiary of the British National Health Service’s superb psychiatric care. So she says nothing about personal incontinuity in her everyday life and still cashes her checks without batting an eye, while telling her gullible readers that personal continuity is an illusion. She would no doubt chuckle (all the way to the bank) if her self-refuting gibberish were called out within the profession because many would rush to defend her.

Blackmore is not a nut because nuts don’t make a lot of money selling their delusions. Rather, she is a sophist, the kind of philosopher for whom Plato reserved the harshest criticism. She’s an articulate huckster who uses pretentious gibberish to obscure the truth and to confuse naïve readers.

Shame on us for taking this woman (or these women?) seriously.

Note: The illustration above is a model of the Greek trireme (three banks of oars), courtesy the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Germany (CC BY-SA 3.0)

You may also enjoy:

My right hemisphere is an atheist! No, wait… In reality, split-brain surgery does not split consciousness in any meaningful sense.

and

No free will means no justice. Materialist biologist Jerry Coyne doesn’t seem to understand what denying free will would mean for the criminal justice system.