How You Can Really Know You’re Talking to a Computer

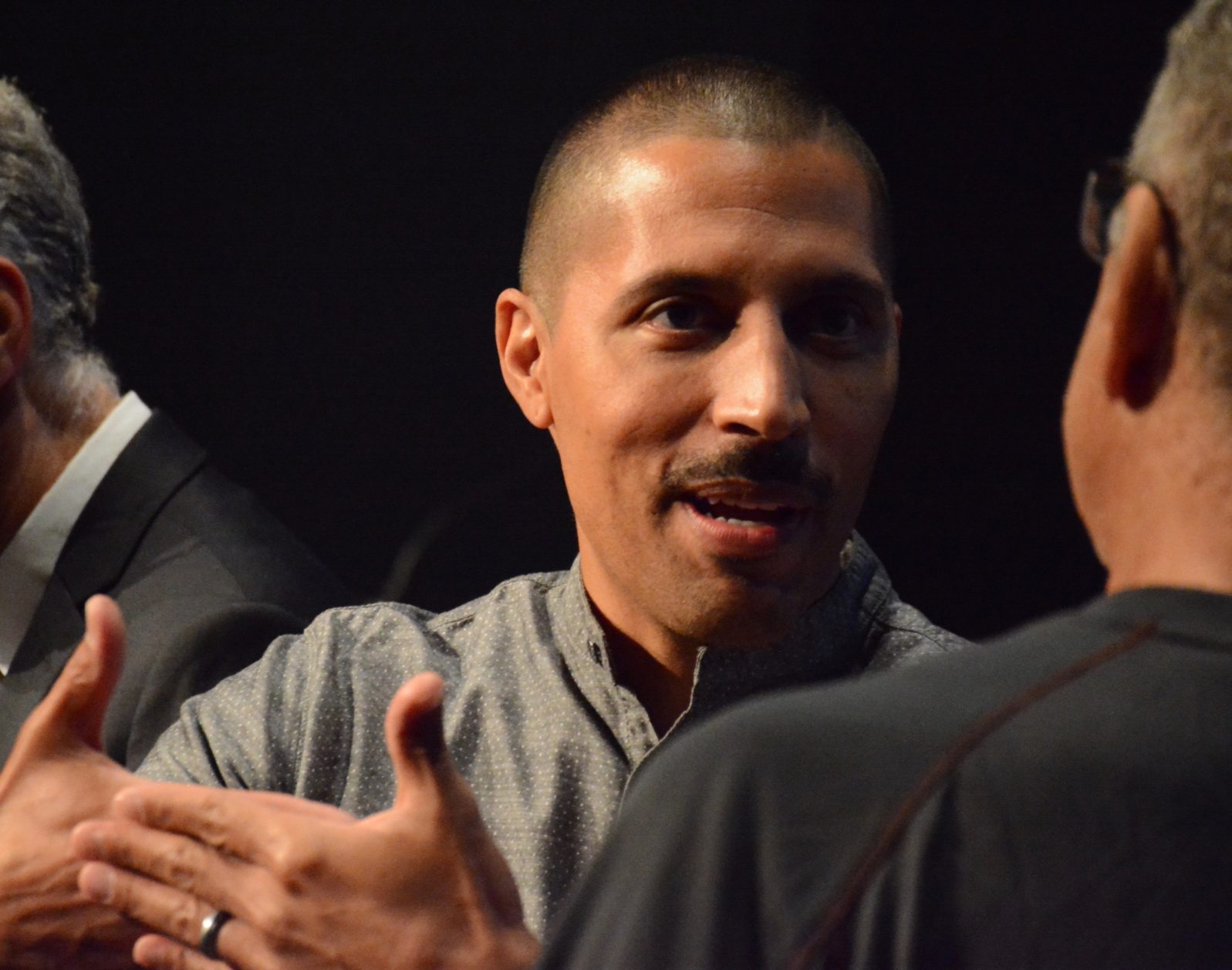

In a lively exchange, computer science experts offer some savvy adviceRecently, Walter Bradley Center director Robert J. Marks and Harvey Mudd College computer science prof George D. Montañez got together to talk about a perennial favorite topic these days, Can machines think? And how would we know? Some excerpts below:

Long ago, computer genius Alan Turing devised a test for computers: The Turing test basically meant that a human simply could not tell the difference between interacting with the machine and with another human. That would show that machines could be built that would think like humans.* The type of machine he sought is called an artificial general intelligence (AGI).

04:36 | How to determine if you are talking to a computer

Robert J. Marks: It’s always easy to determine if you are talking to a computer or a human. You can just ask them to compute the square root of 30 or something because a human would take a while to get the square root of thirty …

George D. Montañez: Depends on the human! We have a professor here, Art Benjamin, who’s the “mathemagician” and you can ask him what the roots of very large numbers are and he can give you an answer. Not as quick as a computer but pretty quick, quicker than most humans.

Robert J. Marks: Can he give the twelfth root of 2?

George D. Montañez: I don’t know if he can do multiples. It’s mostly doing very large numbers. Ask about the root of some number with seven digits and he’ll be able to tell you.

Hint: Humans, even very gifted ones, must think in order to do difficult calculations. A machine dedicated to calculations does not think; it produces a correct answer to any calculation very quickly— provided that the mechanism enables it.

05:18 | Do chatbots pass the Turing test?

Robert J. Marks: We’re familiar with different chatbots. Chatbots come in different flavors. There are the ones you can actually hold a conversation with. There’s also the single exchange chatbot like Alexa and so forth. Do you think that the chatbots that perform the sort of “exchange” conversation are passing the Turing test?

George D. Montañez: No because I don’t think people are actually thinking that they are speaking with a human—unless they’re really small children. So my children happen to think that Google is a person. So they’ll ask, “Google, what is your favorite cartoon? What is your favorite color?” And I have to explain to them, Google is not a person. Google is a system. But most adults would realize that they are not talking to a human when they are speaking to Alexa, I would think.

Robert J. Marks: I think that some of the chatbots were not written to pass the Turing test. I think that they’re done at a lower level. Certainly, Alexa and Google Home isn’t.

Hint: A chatbot will sound correct but without independent thought. The interactive chatbots have an ill-starred history. They depend on reproducing plausible swatches of actual remarks from thinking humans. Unfortunately, they are a tempting target for trolls. Microsoft learned the hard way: In 2016, its chatbot Tay started regurgitating offensive remarks, prompting the threat of a lawsuit from entertainer Taylor Swift. It had to be shut down within a day. But the new, politically correct Zo was merely dull, not inspiring. And Sophia, the vaunted robot-citizen, lost considerable air time and lustre when it somehow picked up the idea that it wanted to “destroy humans.” Good will and good judgment are not easy to mechanize. That may not even be possible.

06:18 | Selmer Bringsjord’s view of the Turing test

Robert J. Marks: Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute’s Selmer Bringsjord said something very interesting over a decade ago about the Turing Test. “Progress toward Turing’s dream is being made. It is coming only on the strength of clever but shallow trickery. For example, human creators of artificial intelligence that compete in present-day versions of the Turing test know all too well that they have merely been trying to fool the people who interact with their agents into believing that these agents really have minds.” Do you concur with that?

George D. Montañez: I think so. Look at, maybe, the best-known example of this, “Eugene Goostman” [claimed to have passed the Turing Test]. The creators of that piece of software actually made the personality of that software be a thirteen-year-old Ukrainian boy because they felt that any mistakes that were made either in factual knowledge or maybe in grammar would be more easily forgiven if the person thought they were chatting with an adolescent versus speaking with an adult. So this is a specific design decision that was made in order to fool people and give their system a leg up. So I think that in some sense, yes, that’s occurring.

Robert J. Marks: Did he talk in a Ukrainian accent?

George D. Montañez: Again, it was all just text messages. The systems don’t actually have speech vocalization. It’s actually based on things that are typed.

Robert J. Marks: I’m just wondering. If he responded incorrectly could they chalk it up to, he’s Ukrainian, English isn’t his first language?

George D. Montañez: Yes, that’s exactly right. So in the messages that they read, they could say, if there were grammatical mistakes or he didn’t understand something that was asked, it’s because English is a second language versus it’s because I’m speaking with a machine.

Robert J. Marks: You have a couple of quotes from Eugene Goostman in your paper. One where Eugene Goostman was asked, “Why do birds suddenly appear?” Isn’t that a line from a Carpenters’ song?

George D. Montañez: I believe it is, yes.

Robert J. Marks: And Eugene replied, “Just because 2 plus 2 is 5. By the way, what’s your occupation? Could you tell me about your work?” It seems that he’s kind of deflecting the problem by asking questions back to the person that’s querying him.

George D. Montañez: Yes.

Robert J. Marks: And that’s an easy way to deflect things. If I was interviewing somebody and they started asking me questions, I would kind of dismiss them because I want to learn about them. I don’t want them learning about me.

Here’s another one: The judge says “Is it okay that I get sick of sick people? How is your stomach feeling? Is it upset today?”

Eugene responded, “I think you can’t smile at all. I bet you work for a funeral agency.”

I don’t know. To me, that doesn’t seem very respondent. I wouldn’t say that that was an intelligent give-and-take.

George D. Montañez: And I wouldn’t either. I put these quotes in the paper to show instances where the system’s responses are seemingly independent of the question asked. This is clever on the part of the programmers in that they built in fallback mechanisms for when they couldn’t actually answer a question well. They just gave a random response. Which, again, if you’re speaking with a thirteen-year-old, thirteen-year-olds do this from time to time. But this isn’t an answer that was actually directly answering the question that was asked.

06:53 | Eugene Goostman — Did this chatbot beat the Turing test?

Robert J. Marks: I don’t think that someone who was really educated would think, based on this short excerpt that we just read, that it had any intelligence at all.

George D. Montañez: Based on that one, no. But you have to figure that, for Eugene Goostman to pass the Turing test, he had to fool greater than 30% of the people. So it did something right. Whatever the system was designed to do, it beat the criterion that was set up for it.

Robert J. Marks: George, what do you think the importance of passing the Turing test is to the establishment of mainline artificial intelligence? Is it an important test? Is it as important as when Turing proposed it back in 1950?

George D. Montañez: There is a principle—I forget the name—that once you start to optimize for a metric, it ceases to be a good metric.

Robert J. Marks: That’s Goodhart’s Law!

George D. Montañez: So I think this is a perfect example of Goodhart’s Law, in the sense that, now that people are specifically trying to beat the Turing test—the thing that it’s supposed to measure—it is no longer a valid test. People are trying to build systems just to pass the Turing test versus building systems that actually have artificial general intelligence (AGI). It would be nice if people were working towards the goal of developing artificial general intelligence systems and those systems just happened to pass the Turing test. Then it would be a good metric. But because we are trying to optimize toward that metric, it ceases to be really meaningful.

Robert J. Marks: Goodhart’s law can be stated thus: Any time we establish a metric as a measure of something we want to do, it is no longer an effective measure for what we want to do. And there’s a followup, and that’s called Campbell’s law. Campbell’s law is that “Goodhart’s law will often lead to trickery and deception” and so that’s exactly what is happening here.

George D. Montañez: Yes.

Hint: Despite what we hear, claims that a machine did or didn’t pass the “Turing test” don’t really mean what was once intended. Even if it passed the Turing test, Eugene Goostman is not a thinking machine. There are good reasons for thinking that such a machine is not possible.

Also, by George D. Montañez:

AI: Think about ethics before trouble begins. A machine learning specialist reflects on Micah 6:8 as a guide to developing ethics for the rapidly growing profession (George Montañez)

And by Robert J. Marks: Why it’s so hard to reform peer review Robert J. Marks: Reformers are battling numerical laws that govern how incentives work. Know your enemy! (A discussion of Goodhart’s law.)

*Note: Some argue that the Lovelace test would be a better one. It focuses not on whether people think the computer is thinking but whether it has independently developed a solution to a problem outside its programming. None has done so.