The Three Laws of Robotics Have Failed the Robots

Almost no one out there thinks that Isaac Asimov's Three Laws could work for truly intelligent AIProlific science and science fiction writer Isaac Asimov (1920–1992) developed the Three Laws of Robotics, in the hope of guarding against potentially dangerous artificial intelligence. They first appeared in his 1942 short story Runaround:

- A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

- A robot must obey orders given it by human beings except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

- A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law.

Asimov fans tell us that the laws were implicit in his earlier stories.

A 0th law was added in Robots and Empire (1985): “A robot may not harm humanity, or, by inaction, allow humanity to come to harm.”

Here’s Asimov discussing his Laws:

Chris Stokes, a philosopher at Wuhan University in China, says, “Many computer engineers use the three laws as a tool for how they think about programming.” But the trouble is, they don’t work.

He explains in an open-access paper:

The First Law fails because of ambiguity in language, and because of complicated ethical problems that are too complex to have a simple yes or no answer.

The Second Law fails because of the unethical nature of having a law that requires sentient beings to remain as slaves.

The Third Law fails because it results in a permanent social stratification, with the vast amount of potential exploitation built into this system of laws.

The ‘Zeroth’ Law, like the first, fails because of ambiguous ideology. All of the Laws also fail because of how easy it is to circumvent the spirit of the law but still remaining bound by the letter of the law.

Chris Stokes, “Why the three laws of robotics do not work” at International Journal of Research in Engineering and Innovation (IJREI)

Maybe we’d better hope it never gets tested in real life? At any rate, here at Mind Matters News, it’s Sci-Fi Saturday so we asked some of our contributors for reactions to the laws and to Stokes’s doubts about them:

Jonathan Bartlett: The laws of robotics utilize ordinary and purposive language. That works for ordinary and purposive human beings. But robots are not human. Therefore, those rules should be adapted to be the rules of the robot-makers, not those of the robots themselves. These can be translated into rules for robot-makers as follows:

Bartlett offers rules for robot makers instead:

1) Robots should only be built with human safety in mind. Designers should recognize that humans can make mistakes and safeguards against preventable mistakes should be built-in.

2A) Robotic behavior should be predictable so that human operators can appropriately understand how the robot’s input will direct its actions. The goal should be to make the behavior understandable/predictable by the human so that the human can work with it in a seamless manner.

2B) There should be clarity regarding which user(s) is in control of the robot, both for the robot itself and for those around it. That is, if a robot is following a task that will lead to danger, it should be clear to others nearby who has the ability and responsibility to cancel the request.

2C) The robot should be built such that the person in control should remain in control unless privilege is explicitly transferred by the original party or is taken by someone with greater privilege (i.e., a foreman, a policeman, etc.)

2D) An exception is that a robot’s actions should be cancellable by anyone nearer to the situation than the operator

2E) Any sequence of robot coordination should not be endangered if any robot’s actions in the sequence are canceled (i.e., canceling the actions of a robot endangering a human should not inadvertently cause danger to other parts of the process)

3) Robots should have internal sensors, controls, and reporting so that they can report to humans any detectable or predictable malfunction before it causes a hazard.

He adds: The laws of robots, as they were envisioned by Asimov, assumed that you could program a computer just as if you were speaking to a human. If we treat robotics as an engineering discipline instead, we can develop rules for robot development that do indeed prevent danger to humans. Imagining the future is fun, and even necessary. However, trying to find appropriate rules for future robots that may never exist should not interfere with developing good ethical ground rules for developing robots in the near future.

Brendan Dixon pops in to say: It’s even worse than he says! The “laws” are ambiguous, even for a human. For example, what does it mean to not “harm”? Actually quite sticky to work out.

The flaw with the laws is this: They assume that morality and moral decisions can be made by means of an algorithm, that discrete yes/no answers suffice to “solve” moral quandaries. They are not sufficient. (Or, to be sufficient would require many, many, many more “laws” than those specified to cover the vast array of “what if” and “but he” qualifications that always arise.)

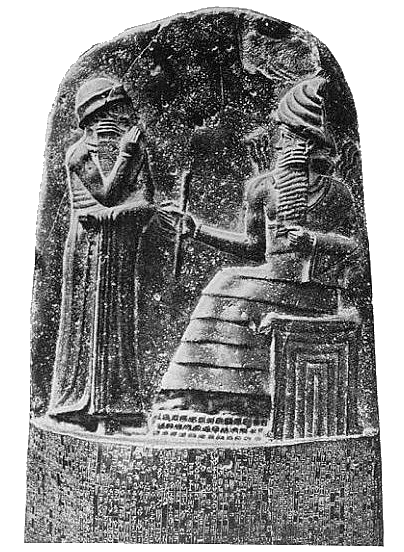

Here is an interesting data point: I recently learned that the Law of Hammurabi (approximately 1750 BC, chiseled into a stele now in the Louvre) was the most frequently copied ancient law code. And yet, in all the law cases we’ve discovered, it is never referenced or used. Why? Because ancient law codes sought to teach users how to think about making wise decisions vs. encoding specific rules about the decisions you should make. This highlights the challenge of robotics: Robots would require that we can code into rules the decisions they should make, but moral decisions require wisdom, a mind trained how to think so that it can handle each case properly.

Eric Holloway offered: I find it ironic that while there are supposedly objective moral laws for robots, humans themselves do not have objective moral laws

I wonder if a logical consequence of the 3 robot laws that the robots must teach humans objective moral laws, e.g. in order to avoid “through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.” So, for instance, the robots would bring a halt to all war, abortions, and euthanasia throughout the world, and embark on a massive evangelization effort to prevent humans causing themselves infinite harm by going to hell.

Brendan Dixon responded by identifying the underlying conflict between the 0th law and the others: Nice thought, but it assumes a definition of harm with an individualized focus. What if harm instead (and I don’t agree with this) is measured in utilitarian terms at the level of a population? Whole other ball game. That’s the problem.

Eric Holloway suggested how the robot might think that out: In which case, the best way to minimize harm to the population is to wipe out everyone. Of course, there is a lot of short term harm in wiping out everyone, but it is much less in aggregate than the accumulation of harm throughout many thousands of future generations. Or, a bit less extreme, sterilize everyone. That way minimize harm to currently existing humans, and there will be no future humans to be harmed.

Well! Perhaps it’s a good thing that artificial general intelligence of the sort Asimov was trying to make laws for is doubtful for a variety of reasons anyway.

Here’s Computerphile’s view: The Laws never worked even in fiction. Asimov’s robot books “are all about the way these laws go wrong, with various consequences.”

Just for fun, Eric Holloway explains why “friendly” artificial intelligence will kill you:

Is that a shocking idea? Let’s follow the logic: We don’t want to invent a stupid god who accidentally turns the universe into grey goo or paperclips, But any god we create in our image will be just as incompetent and evil as we are, if not more so. A dilemma!