Should You Pay For a Virtual Private Network (VPN)?

Here's what a VPN can and can't do for youEvery day we hear of data breaches, where personal information is collated and analyzed for the use of big content providers. Are virtual private networks (VPNs), where your messages are encrypted while traveling over the internet, the answer?

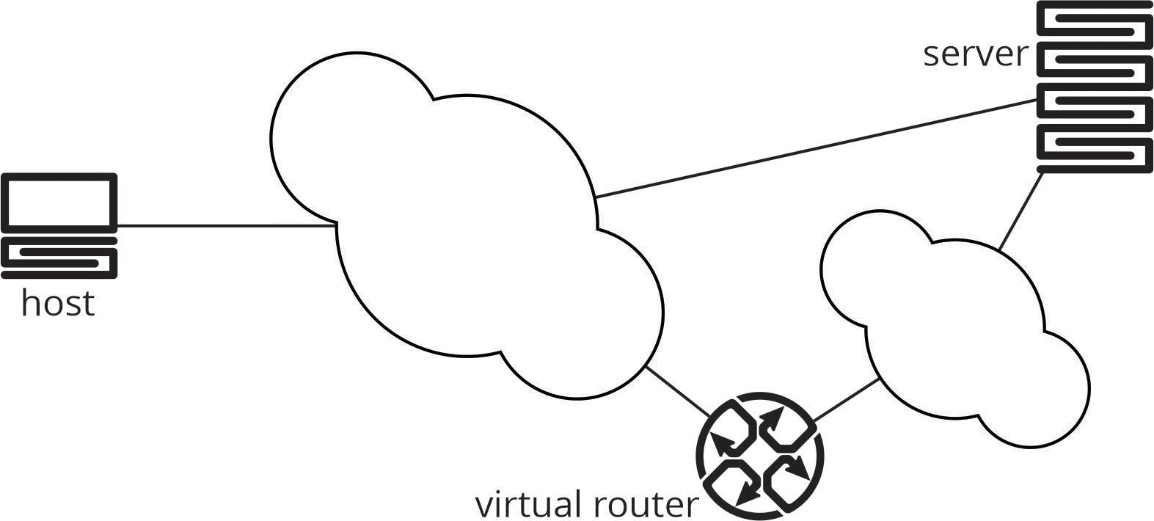

This figure shows how a VPN works:

When a host, such as a laptop, tablet, cell phone, etc., connects to an Internet-based service, it is building a connection to a server. Usually, it is connecting to a data center, either one that is owned and operated by the company providing the service or the service is running in a public cloud.

Don’t be misled by the term “cloud.” No matter where the service is located, it is running on a physical server which has all the same kinds of resources as your laptop (or any other computer).

Normally, your connection from the host to the server runs over the Internet Protocol and the information carried through the network is not protected in any way. In other words, anyone with the right equipment and knowledge can read the data you are sending to the service (including your bank account information, the contents of your email, etc.). In the illustration above, the host connects to the server across the larger cloud in the figure above (which represents the internet) directly.

When organizations began using the internet to allow their employees to connect to internal email systems, they wanted to protect their information in some way — resulting in the invention of the VPN. In the illustration above, the host connects through the smaller cloud to the virtual router through an encrypted tunnel. Once the traffic reaches the virtual router (which is called the tail end of the tunnel), it is decrypted and transmitted “in the clear” to the server.

The original purpose of a VPN, then, was to connect a trusted endpoint (or network) over an untrusted network by carrying data across an encrypted tunnel to another trusted endpoint or network.

Now, here’s the problem: If you are an average internet user, there is no “trusted network” on the other end of the encrypted tunnel. The VPN tunnel is connected to the same global network—the internet—as your host. Given this situation, what can a consumer VPN protect you against?

The first, and most obvious, answer is: Consumer VPNs can protect you against untrusted links between your computer, tablet, or phone and the virtual router which terminates the VPN tunnel. For instance, if you are in a public place such as a coffee shop or hotel or using paid wireless access in a foreign country, the link between your computer and the first wired connection is vulnerable to Man in the Middle (MITM) attacks of various kinds. Someone who attacks this vulnerable wireless link can capture your traffic and see any personal information being sent between your computer and the server.

Not everyone watching this connection is an attacker, however. Many wireless services act as an MITM for various reasons, both legitimate and illegitimate. Wireless service providers, including those providing services to coffee shops, hotels, and many other public places, are all just as hungry for information as large-scale content providers are. If you don’t want them to gather data on you, VPNs can protect your link when you are connecting to services on the Internet.

Building on the concept of a VPN, many servers can (and will) encrypt the traffic from your computer to the server itself—this is the meaning of the “little green lock” you might see in the address bar of your web browser. These encrypted sessions can, however, be intercepted by an operator who “owns the wire” between your computer and the server, particularly along the edge of the network (again, such as the wireless connection you might use at a coffee shop, hotel, or other public space). Using a VPN can prevent these sessions from compromise until they reach deeper into the Internet—to the virtual router where the encrypted tunnel terminates—providing a lot more protection for your data.

Can a VPN protect your data from attackers throughout the entire internet? The answer is “no.” An attacker who can intercept your traffic between the virtual router and the server can still examine your data as it is carried across the public internet.

Can a VPN protect your privacy from services such as Google or Facebook? Clearly not—the VPN service just carries your data in an encrypted form away from your local access links, dumping it on the internet in its original form at that point. These services will still see, and consume, any information you send to them.

Are there other “holes” in these VPNs? Some services might not protect the information you send through the DNS system, nor will they prevent your browser (or device) from being “fingerprinted.” That is, when you are using a VPN service, unless the service takes specific steps to eliminate leakage of any information which can be used to identify you, you are not “anonymous.”

Are you better off using a VPN service? The answer to this question is: it depends. In some cases, specifically when you are using public wireless services, using a VPN can add measurably to your privacy and security.

But VPNs are not a “silver bullet” in solving the many security and privacy issues users face today.

Further reading on why we are not as “anonymous” as we think:

“Anonymized” data is not confidential. It is almost as anonymous as your fingerprint, actually

Our anonymity may be an illusion. Because we talk about ourselves so much online, few leaked pieces may even be required to identify us.

Many parents ignore the risks ofposting their kids’ data online. The lifelong digital footprint, which starts before birth, makes identity theft much easier.

Ad exec quit the industry over Big Tech’s relentless snooping. He was shocked by the brazen attitude to invasion of privacy.

Your phone knows everything now.

And it is selling your secrets

Featured image: Virtual Private Network VPN/ stanluc, Adobe Stock