Will Facebook’s New Focus on “Community” Groups Prevent Abuses?

When you look a little closer at the proposal, you will see that the answer is noSocial media giants, such as Facebook and Twitter are accused of stoking violence and violating privacy (doxxing). As a result, governments are taking a new, harder line: Spain fined Facebook $600,000 in 2018. The European Union fined Facebook $122 million in 2017. But these laughable amounts are straws in the wind, of course. Facebook risks a multi-billion-dollar fine from the U.S. Federal Trade Commission over the Cambridge Analytica scandal, in which 87 million users’ information was improperly shared with a political consulting firm. And, as for Google, Bloomberg says it all: “Google Should Be Afraid. Very Afraid. A new round of antitrust questions can’t go well for the company. The culture has turned against tech since Google skated free in 2013″ (June 1, 2019).

The giants have responded with the expected defenses: The world cannot survive without them; they bring massive economic gains; they are “doing their best to censor bad actors”; and even that they are “just platforms,” hence not responsible for the abuse of the systems they have created. But one additional argument merits a closer look.

Facebook’s traditional model aimed at growing accounts with a massive social media following; now, it says it wants to focus on developing smaller groups. As CEO Mark Zuckerberg told the New York Times in April, the firm is shifting “away from being a public town square and to private communications.”

How is that supposed to help? Social media were originally designed to support such existing relationships. But they quickly morphed into platforms that focused on helping people build large followings. Why? It’s a matter of economics.

Social media networks are expensive to operate. According to some sources, Microsoft alone has more than 1.6 million computers (servers) in operation in their data centers. Amazon and Alibaba are probably around the same size, Facebook is probably a bit smaller, and Google is probably much larger. Even a “smaller” media network, such as Twitter or LinkedIn, require running hundreds of thousands of computers in large-scale data centers.

These data centers are not cheap to build or run. Data center analyst João Marques forecast in 2017 that data centers might consume 1/5th of the world’s power output by 2025. The centers require massive power handling systems, cooling systems, network infrastructure (computer networking equipment), miles of optical cabling, and—the most expensive asset—hundreds, thousands, or tens of thousands of employees. Where does the money come from to pay for all of this?

The money comes from these social networks’ ability to shape the market in ways that benefit the companies that pay them for a chance to tap into them. This power is the easiest to wield with a single person or organization that has lots of influence, that is, followers. So the shape of the social media is driven by their need to build the influence networks on the one side and find those who will pay to tap in on the other.

You would think, based on the description above, that focusing on smaller, organic communities would destroy the social media’s immensely profitable model: There will no longer be individual influencers with millions of followers who can act as a gateway into entire markets. Surprisingly, that’s not true. If anything, the move towards communities will increase the power of these social media giants. To understand why, look at the basic structure of a social media network:

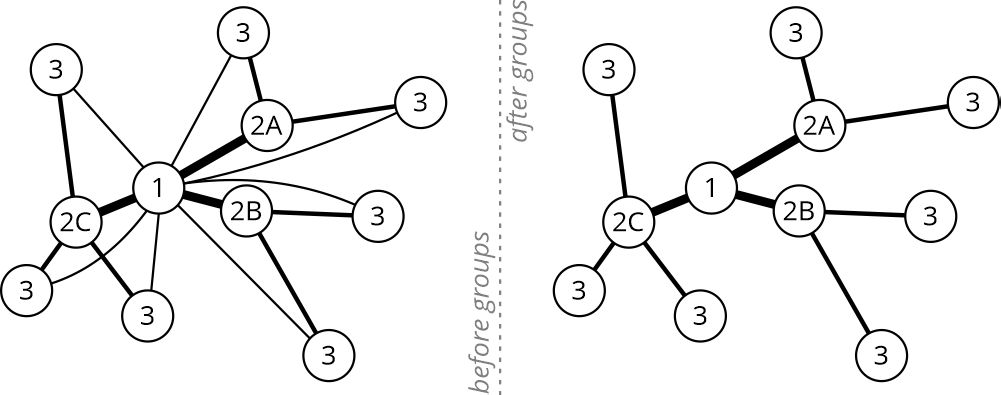

This figure represents a very simple social graph, which is one of the kinds of information social media networks build out of the information their users provide. The thickness of the line in this illustration indicates the strength of the connection (which could include things like the amount of information which flows over the link or the amount of trust one person or group places in another, etc.). Whether the labeled nodes (circles) are individuals or groups does not matter for the purposes of this illustration.

The figure at left is the current personality-focused model, where the person or group at the first tier (supernode 1) would be the focus of everyone in the network. Individuals (or groups) build a large following through the entire social network. After the change to a more group- focused interface (the figure at the right), the ties of individuals to their “group leader” or to the group identity itself will become more pronounced while their ties to the “core node” (1) will either be weakened or eliminated.

This change reduces the apparent importance of supernodes (node 1 in each of the illustrations). That reduces the advantage of building large, sweeping networks of followers. Instead, more emphasis will be placed on local community leaders. Further, the resulting community feels more like a community; a smaller, safer space within a larger world, with somewhat clear (but permeable) boundaries between the community and the “rest of the world.”

What is not apparent to the user of the social network, however, is that the shape of the network, and information flow through the network have not changed. The primary flow of information is still through the network, first up the hierarchy and then back down. The network itself still acts as a primary filter on the information passed among the participants. “Community leaders” can block information from being passed through into the community but can do little to ensure that information is propagated into the community.

Super influencers (supernode 1) still have a profound influence within the network, even though it is not as visible. The connections of and influences on individuals within the network are still exposed to the social media service itself, so there is little change in the state of privacy.

Thus, the move to a more group-focused interface gives the appearance of stronger privacy and community orientation but the structure and logic of social media ensure that these are appearances rather than realities. To “solve” the problems social media networks impose on culture, we must develop a deeper understanding of their internal organization and driving logic. We must ultimately ask: what is gained, and what is lost, in our dependence on these systems? Are they worth it?

See also: A scientist’s nightmare: Doxxed on Twitter

and

Facebook’s old motto was “Move fast and break things”