How Can Mere Products of Nature Have Free Will?

Materialists don’t like the outcome of their philosophy but twisting logic won’t change it

Most of us assume we have free will. But if we live in a universe where everything is totally governed by laws of nature (a deterministic universe), we must ask ourselves an important question: Is our own free will compatible with total control by the laws of nature? There are only two fundamental positions on the issue: Either our free will is compatible with such laws (compatibilism) or it isn’t (incompatibilism).

It’s important to note that this is a logical question, not an empirical question that can be addressed by citing evidence. Does it make sense logically to say that determinism is true and at the same time that free will is real? In this post, I will address only the logical (metaphysical) question, rather than the many legal and political issues regarding determinism and free will.

The nature of the debate has changed in modern times. The historical debate about free will was theological. It centered on divine agency as compared with human agency. For example, did people make a free choice to accept salvation or was God really directing the choice?

The modern debate centers on a scientific understanding of determinism. If determinism is true—that is, if every state of the universe is determined from moment to moment entirely by the laws of nature (physics, chemistry, etc)—how is it possible that we could have free will? It is certainly true that we don’t have control of natural laws—I cannot change gravitation or electromagnetism simply by willing it. Thus, it seems obvious that I cannot have free will in a deterministic universe. It seems obvious then that compatibilism is false and incompatibilism is true.

Here is my view: I believe that genuine (“libertarian”) free will is real and that free will is logically incompatible with determinism in nature.

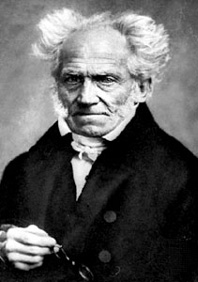

Among compatibilists, who believe that free will is consistent with determinist laws of nature, some are theists and dualists and some are atheists and materialists. Daniel Dennett, for example, is a famous atheist and materialist who is a compatibilist. Compatibilists usually deal with the problem in logic by invoking definitions of free will that differ from the libertarian idea of free will as a first cause of a series of causes. Philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788-1860) expressed it thus:

Man can do what he wills but he cannot will what he wills.

Schopenhauer means that our motives are determined but we are (in some sense) free to act on our motives. In Schopenhauer’s sense, free will is essentially autonomy, the ability to act according to internal drives without external constraint.

I think that compatibilists’ efforts to avoid the obvious — that free will and determinism can’t both be true — fail in every instance. If determinism is true, then our actions are determined by natural forces over which we have no genuine control and free will is an illusion.

Compatibilists hold their view, I believe, because they believe that determinism is true and also that we unquestionably have some kind of freedom to act or not act according to our choices. Although most compatibilists have a more or less materialist view of nature, they find it impossible to shake the conviction that free will is real. Stuck between an affirmation of determinism and an affirmation of some kind of genuine freedom of choice, they prefer to twist logic and reason to accommodate their cognitive dissonance, rather than jettison one of their beliefs.

Nonetheless, compatibilism is incoherent. Sophistry notwithstanding, if determinism is real, we are not free.

But is determinism real? That is a question for another post.

Note: The term “libertarian” sometimes refers to a political philosophy that favors minimal government. But the meaning used here is the philosophical idea that we can make truly free choices.

Michael Egnor is a neurosurgeon, professor of Neurological Surgery and Pediatrics and Director of Pediatric Neurosurgery, Neurological Surgery, Stonybrook School of Medicine

Also by Michael Egnor: Does brain stimulation research challenge free will?

Is free will a dangerous myth?

Also: Has science shown that consciousness is only an illusion? (a look at Dennett’s position)