Artificial Intelligence Is Actually Superficial Intelligence

The confusing ways the word “intelligence” is used belie the differences between human intelligence and machine sophisticationWords often have more meaning than we hear at first. Consider colors. We associate green with verdant, healthy life and red with prohibition and danger. But these inferences are not embedded in the basic meaning of “red” or “green.” They are cultural accretions we attach to words that enable the richness of language. That, by the way, is one reason why legal documents and technical papers are so difficult to read. The terms used are stripped clean of such baggage, requiring additional words to fill the gaps.

The word “intelligent” is like that. Saying that a computer, or a program, is intelligent can lead us down a rabbit hole of extra meaning. An honest researcher merely means the computer has produced a result we normally associate with intelligence. That is, the result looks like the activity of an agent (that is, a person) known to possess intelligence. But to the rest of us, used as we are to being imprecise with our words, the term conveys much more: that the computer is becoming intelligent like us. And that it may soon surpass us.

Some experts believe that the computer will become like us and surpass us; some do not. Both groups may use the term “intelligent” but mean different things. The loose, confusing ways the term is used conceal important differences between the way human beings think and the way machines process data. Let’s look at some of them:

We’ve known, for as long as we’ve had chess-playing programs, that computers do not play chess like we play chess. We’ve lost sight of that difference because recent artificial intelligence (AI) program advances have overcome higher hurdles than previous programs. Computers now win at dynamic strategy games, translate languages, analyze MRIs, and even recognize cats. These advances seem, on the surface, to convey the idea that more is going on than mere programming, that computers are living up to their designation as “intelligent” in the same sense as a human being.

But we should know better. And recent research into how the latest advances differ from human mental activity demonstrates that.

Recent AI — Deep Learning—works by means of layers of programming. Each layer, in effect, reduces the problem a bit, handing it off to the next layer, until the final layer emits a result. Careful tuning of the layers, assisted by techniques such as backpropagation, eventually create networks that can provide reliable answers within their known domain (e.g., such as recognizing cats). The system achieves this result because each layer tosses aside bits that are not relevant to the problem. A researcher explains:

The conception goes something like this: because of their ability to discard useless information, a class of machine learning algorithms called deep neural networks can learn general concepts from raw data— like identifying cats generally after encountering tens of thousands of images of different cats in different situations. This seemingly human ability is said to arise as a byproduct of the networks’ layered architecture. Early layers encode the “cat” label along with all of the raw information needed for prediction. Subsequent layers then compress the information, as if through a bottleneck. Irrelevant data, like the color of the cat’s coat, or the saucer of milk beside it, is forgotten, leaving only general features behind. Information theory provides bounds on just how optimal each layer is, in terms of how well it can balance the competing demands of compression and prediction. Santa Fe Institute, “Information theory holds surprises for machine learning” at Phys.org

Humans do this all the time: Put a dog costume on a cat and we’ll still see a cat. We know enough to ignore the costume and see the cat. In a sense, we compress the canine information we receive to get at the feline essence. AI researchers had hoped (suggested? argued?) that Deep Learning systems do, more or less, the same thing. It turns out, they don’t.

The Santa Fe researchers found that, while Deep Learning systems do compress the information received, they compress it in a wholly different way than humans would:

Given the choice, it is just as happy to lump “martini glasses” in with “Labradors,” as it is to lump them in with “champagne flutes.” Santa Fe Institute, “Information theory holds surprises for machine learning” at Phys.org

That is why we can easily fool computers:

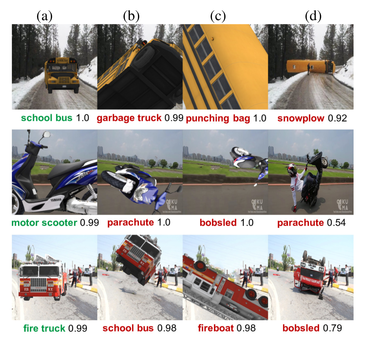

A fire truck, for example, seen from head on, could be correctly recognized. But once pointed up in the air, and turned around several times, the same fire truck is mis-classified by the neural net as a school bus or a fireboat or a bobsled. Tiernan Ray, “Google’s image recognition AI fooled by new tricks” at ZDNET [See illustration above.]

Misclassifying a teapot as a golf ball was an amusing recent illustration; misclassifying humans as animals, however, has been controversial and embarrassing.

So, once again, despite advances that seemingly put computers within reach of human-like intelligence, their internal operations belie the notion: Computers are not intelligent like humans. Though they may — through force of programming and clever engineering (both courtesy of humans) — yield results we associate with intelligence, they do not understand what they are seeing.

Years ago, when expert systems and Prolog were all the rage, an associate of mine quipped that we should refer to what computers do as “Superficial Intelligence” and not “Artificial Intelligence.” The latter term carries overtones of the real item, the former one correctly identifies the fact that Deep Learning has only the appearance of intelligence. I thought he was correct then, and I think so still. Humans are intelligent. Computers only fake it.

Brendan Dixon is a Software Architect with experience designing, creating, and managing projects of all sizes. His first foray into Artificial Intelligence was in the 1980s when he built an Expert System to assist in the diagnosis of software problems at IBM. Though he’s spent the majority of his career on other types of software, he’s remained engaged and interested in the field.

Brendan Dixon is a Software Architect with experience designing, creating, and managing projects of all sizes. His first foray into Artificial Intelligence was in the 1980s when he built an Expert System to assist in the diagnosis of software problems at IBM. Though he’s spent the majority of his career on other types of software, he’s remained engaged and interested in the field.

Also by Brendan Dixon: AI Winter Is Coming: Roughly every decade since the late 1960s has experienced a promising wave of AI that later crashed on real-world problems, leading to collapses in research funding.

and

The “Superintelligent AI” Myth: The problem that even the skeptical Deep Learning researcher left out