Unborn Child Learns the Accents, Rhythms of Mom’s Native Language

There is, however, a dark, little-told tale about how we learned much of what we know about unborn children todayNeuroscientist and journalist Darshana Narayanan tells us at Aeon that when babies are born, they cry “in the accent of their mother tongue.” Her findings add to what we have been learning about mental life prior to birth, especially around language learning. For example,

Recent studies of prematurely born infants – conducted just a few years ago by Kimbrough Oller at the University of Memphis – have brought to light that fetuses born as young as 32 weeks (eight weeks before the usual date) do more than cry. They produce protophones, the infant sounds that eventually turn into speech. Meaning that a fetus in the last trimester of pregnancy can make all the sounds of a newborn infant.

Darshana Narayanan, “Baby talk,” Aeon, July 25, 2024

She asks,

How then does our ability to vocalise come to be? Is it in our nature – ‘in-built’, ‘instinctive’, ‘inherent’, ‘innate’, ‘programmed’, ‘hardwired’, ‘in our genes’? Or is this ability ‘acquired’, ‘learned’, ‘absorbed from our environment’ – is there some nurture to speak of, even in the womb? If so, how much? Is it 80 per cent nature and 20 per cent nurture? Is it 90/10? 30/70? Or some other split? What I hope to do is convince you to drive a stake through the heart of the nature versus nurture debate – often framed as a fight for causal supremacy between two opposing factions – it gets us nowhere.

Narayanan, “Baby talk”

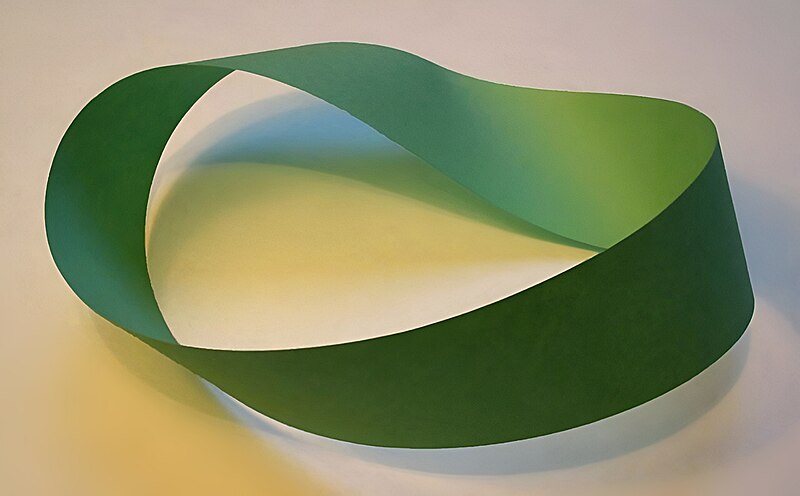

Good question, and she offers a creative answer: She suggests that nature and nurture be seen as a Möbius strip, where there aren’t really two sides: “at no point can that process be neatly partitioned into silos of nature or nurture.”

For example, language learning begins in the womb as prosody (learning the rhythm of speech), not as recognizing the meaning of words:

Language learning begins in the womb, and it begins with prosody. Exposure to speech in the womb leads to lasting changes in the brain, increasing the newborns’ sensitivity to previously heard languages. The mother’s voice is the most dominant and consistent sound in the womb, so the person carrying the fetus gets first dibs on influencing the fetus. If the mother speaks two languages, her infant will show equal preference and discrimination for both languages.

Narayanan, “Baby talk”

By contrast, another team reported that, when 30 French and German newborns — from families that spoke only one of those languages — were studied, the infants’ varied according to the language: “the French newborns tended to cry with a rising – low to high – pitch, whereas the German newborns cried more with a falling – high to low – pitch. Their patterns were consistent with the accents of adults speaking French and German.”

Clearly, the children learned these accents in the womb. But perhaps that falls somewhere between nature and nurture. That is, they learned it but no one was intentionally teaching them or — apart from advanced neuroscience technology — even knew they were doing it.

A dark understory

There is, however, a little-told tale about how much that we know about unborn children today came to be discovered before the age of ultrasound. As Narayanan recounts, over a period of 25 years beginning in the 1930s, Pittsburgh anatomist Davenport Hooker (1887–1965) got hold of 149 babies aborted by the mother’s choice (elective abortions) between the ages of six weeks to 45 weeks. Yes, that’s five weeks after the usual time of birth. He filmed the babies as they struggled, cried, and died, then handed the “fetal tissue” over for dissection.

Thus he and colleagues learned a lot about embryology — and helped to cement cultural Darwinism:

The work of Hooker and Humphrey uncovered the close evolutionary ties we have to the other animals who share our planet. Though timelines may vary, terrapin reptiles, carrier pigeon birds and fellow mammals like rats, cats and sheep share a similar development sequence. In all of these species – ours included – the tactile system is the first to come online, and sensation begins in the perioral area, which is innervated by the fifth and largest cranial nerve: the trigeminal nerve.

Narayanan, “Baby talk”

The photos received wide distribution. I remember a book called The First Nine Months of Life (Simon & Schuster 1962) by Geraldine Lux Flanagan, wondering at the time where the researchers got all that information… Now we know.

A logical conclusion resisted

Narayanan does not seem much troubled by that; on the contrary, she seems troubled by pro-lifers’ use of the photos to assert the humanity of unborn children. She frets,

The portrayals helped propagate a myth of independent fetal life – a way of thinking that had not existed publicly when Hooker began his research. In the 1970s, anti-abortion activists began using his work to plead their cases, including in briefs to the US Supreme Court.

Narayanan, “Baby talk”

In her view, “Political manoeuvrings to grant fetuses personhood, separate from their mothers, are not grounded in science.” To support her no-rights position, Narayanan asserts feebly that the mother and child are “a fused entity,” which will doubtless seem strange news to the mothers of sons…

In reality, the information she writes about — presumably “grounded in science” — is precisely what continues to drive — and must drive — the pro-life movement worldwide. Science is not a publicity engine for fashionable progressive causes.

You may also wish to read: Study: Babies start learning their home language before birth. Neuroscience researchers found that newborns responded better to a folk tale in French than in Spanish or English — when French was their mothers’ native language. Before birth, the child is hearing the rhythm of speech rather than individual words through the amniotic fluid; that may speed learning later.