What Do the “Laws of Nature” Actually Explain?

To what extent does the phrase simply stand in for an explanation?The question of what the “laws of nature” actually explain is worth asking when we consider the way the term is sometimes used. Norwegian philosopher Daniel Joachim Kleiven points to an example in The Grand Design by Stephen Hawking (1942–2018) and Leonard Mlodinow: They argue that the history of science can be summarized as “the long process of replacing the notion of the reign of gods with the concept of a universe that is governed by laws of nature.”

But, Kleiven (pictured) probes, what is the precise nature of the change we are asked to applaud? He quotes the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951), who specialized in mathematics and logic:

At the basis of the whole modern view of the world lies the illusion that the so-called laws of nature are the explanations of natural phenomena. So people stop short at natural laws as at something unassailable, as did the ancients at God and Fate. And they both are right and wrong. But the ancients were clearer, in so far as they recognized one clear conclusion, whereas in the modern system it should appear as though everything were explained. – Wittgenstein, L. (1922). Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. Edinburgh: The Edinburgh Press, 6.371-2

Kleiven comments,

Of course, much hinges on what is meant by “explanations” by Wittgenstein above. If we’re satisfied with describing some abstract way to relate a specific phenomenon to more general ones, then we’re most likely fine. If we want more than that, as if we want to say something about the nature of the phenomena we’re investigating or the world’s intelligible character, we’re confronted with the surprising proposition that all throughout history, “a law of nature” has never explained anything like this. Observing “regularities” in nature, even cataloging them to the extent that we can characterize them with mathematical precision, hardly counts as “explaining” those patterns, rather than just restating them using different terminology.

– Daniel Joachim Kleiven, “The laws of nature explain very little,” IAI.TV, June 16, 2023.

What does Kleiven (or Wittgenstein) mean here? Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy tells us, “Science includes many principles at least once thought to be laws of nature: Newton’s law of gravitation, his three laws of motion, the ideal gas laws, Mendel’s laws, the laws of supply and demand, and so on,” adding, “ the basic question is: What is it to be a law?”

As Stanford Encyclopedia asks, “What is it to be a law?”

Newton’s laws of gravitation and motion tell us what we should expect to happen if no other factors intervene. But these laws don’t explain themselves. Kleiven quotes philosopher Edward Feser on the explanatory problem that the “laws of nature,” considered in isolation, represent. Think of the motions of the planets, for example:

“Planets always move in elliptical orbits. I wonder what explains that?” Suppose I answer: “Kepler’s first law explains that.” You then ask: “Oh, how interesting. What is Kepler’s first law?” And I respond by telling you that Kepler’s first law states that planets always move in elliptical orbits. Obviously, we’ve gone around in a circle.” – Feser, E. (2019). Aristotle’s Revenge: The Metaphysical Foundations of Physical and Biological Science. Heusenstamm: Editiones Scholasticae.

For that matter, why do we live in a universe where things fall down and not up? Why will things keep moving indefinitely unless they are acted on by a force (Newton’s First Law of Motion)?

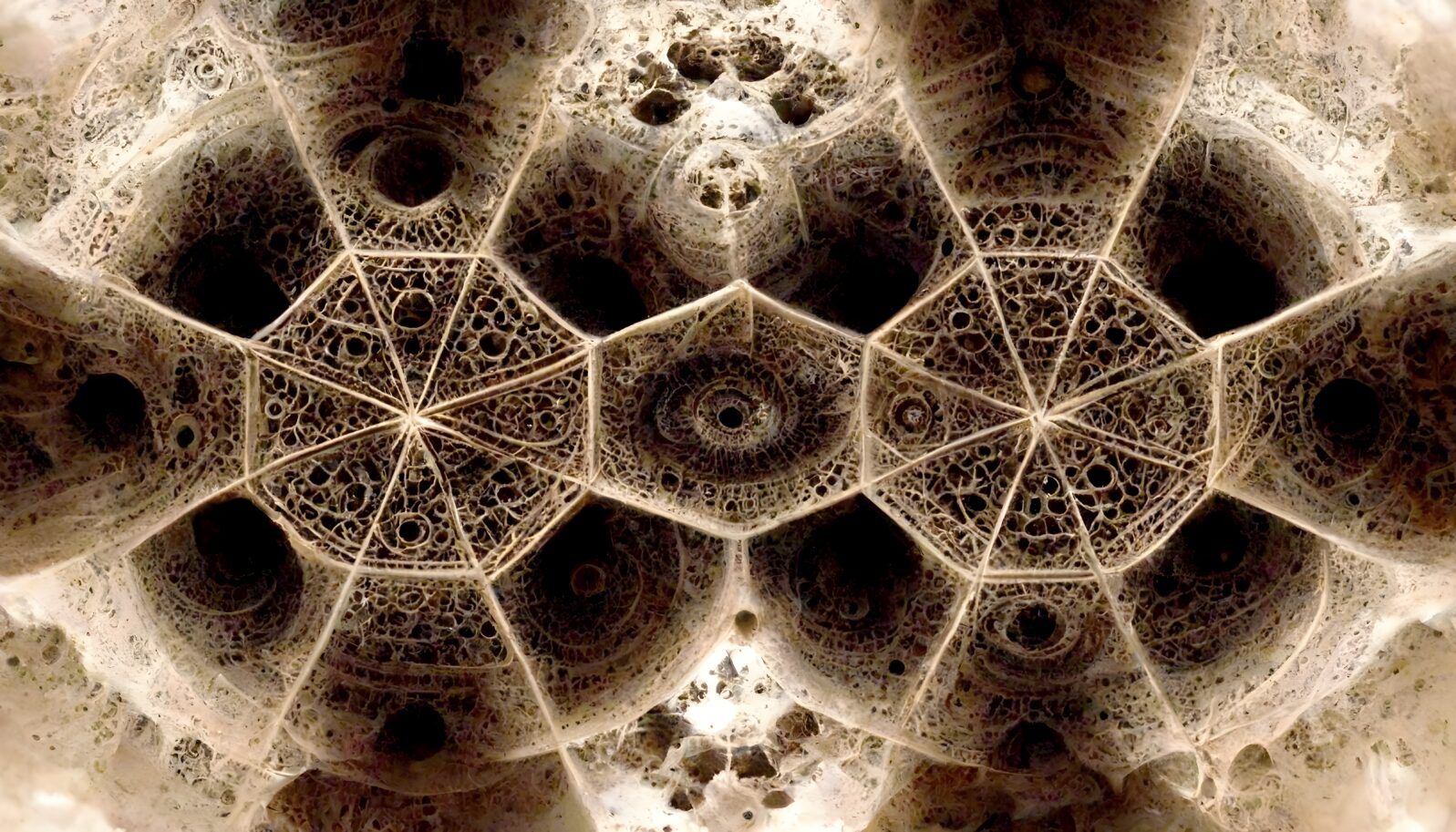

We live in a universe where time runs in only one direction, which is an anomaly among the forces in our universe. But stating that fact as a law is not the same as giving an explanation. The beautifully rendered explanation below offers an account in terms of entropy. Entropy always increases:

Yes, that’s true. Entropy summarizes in one word a lifetime of observations: All life is mortal and every physical thing decays. But even here, a statement of the universal law is not itself a final explanation. Why isn’t this a universe in which time goes backward or in both directions at once or never moves at all? How was that initial decision made?

As Kleiven notes, there is no substantial difference between attributing an orderly exception-free flow of events to the “laws of nature,” and attributing it to the “reign of gods.” Except for one thing: Our remote ancestors seem to have envisioned the immortal gods as often unpredictable, prone to cataclysmic fits of temper with awful results.

The great religions of later eras offer a different picture: The divine intelligence that ordains the universe is a lawgiver who follows and enforces sure laws that create stability, order, and harmony: “When I consider your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place,”… (Psalm 8:3). We find similar sentiments across the planet. But this insight did not arise from science. Rather, it was one of the factors that gave birth to science.

Kleiven offers that, to make sense of our universe, we must assume that there is an agency behind or within nature:

Simply naming these patterns leaves untouched the issue as to the necessary prerequisites of those patterns. If we are to enjoy the luxury of maintaining explanatory power of how and why chess pieces move around the board, we have to invoke agency. In some sense, that could be true of everything from human cultures and moral behavior to the formation of hydrogen molecules and quantum particles as well. Without agency, everything grinds to a halt. – Kleiven, “The laws of nature explain very little,” IAI.TV.

Does he mean something like a designer of the universe? Apparently not. He hopes to avoid appealing to an Agent by arguing that, from an Aristotelian perspective, “laws of nature” is really “laws of the natures of things”:

Rather than positing something outside of the natural entities that laws are supposedly “governing”, the resulting regularities are really just expressions of how things will behave given their inherent natures. This is a possible golden mean between relying on external agent for the prescriptive force of nature, such as God or Platonic forms, or giving up their explanatory power entirely, as with regularity or instrumentalism. – Kleiven, “The laws of nature explain very little,” IAI.TV.

Unfortunately, his alternative approach (Stuff Inherently Happens That Way) leaves us back where we started, though we have at least been to some interesting places. And that’s probably where we will always find ourselves if we try to envision ultimate agency without an Ultimate Agent.

You may also wish to read: “Emergence”: The college level version of “we don’t know how” The word often permits the improbable to be considered probable for the purposes of sounding like science without providing any.