Can Animals Be Held Criminally Responsible for Their Acts?

While the idea is handled provocatively in philosophy literature, in practice, animals are envisioned as plaintiffs, not defendants, in animal rights cases

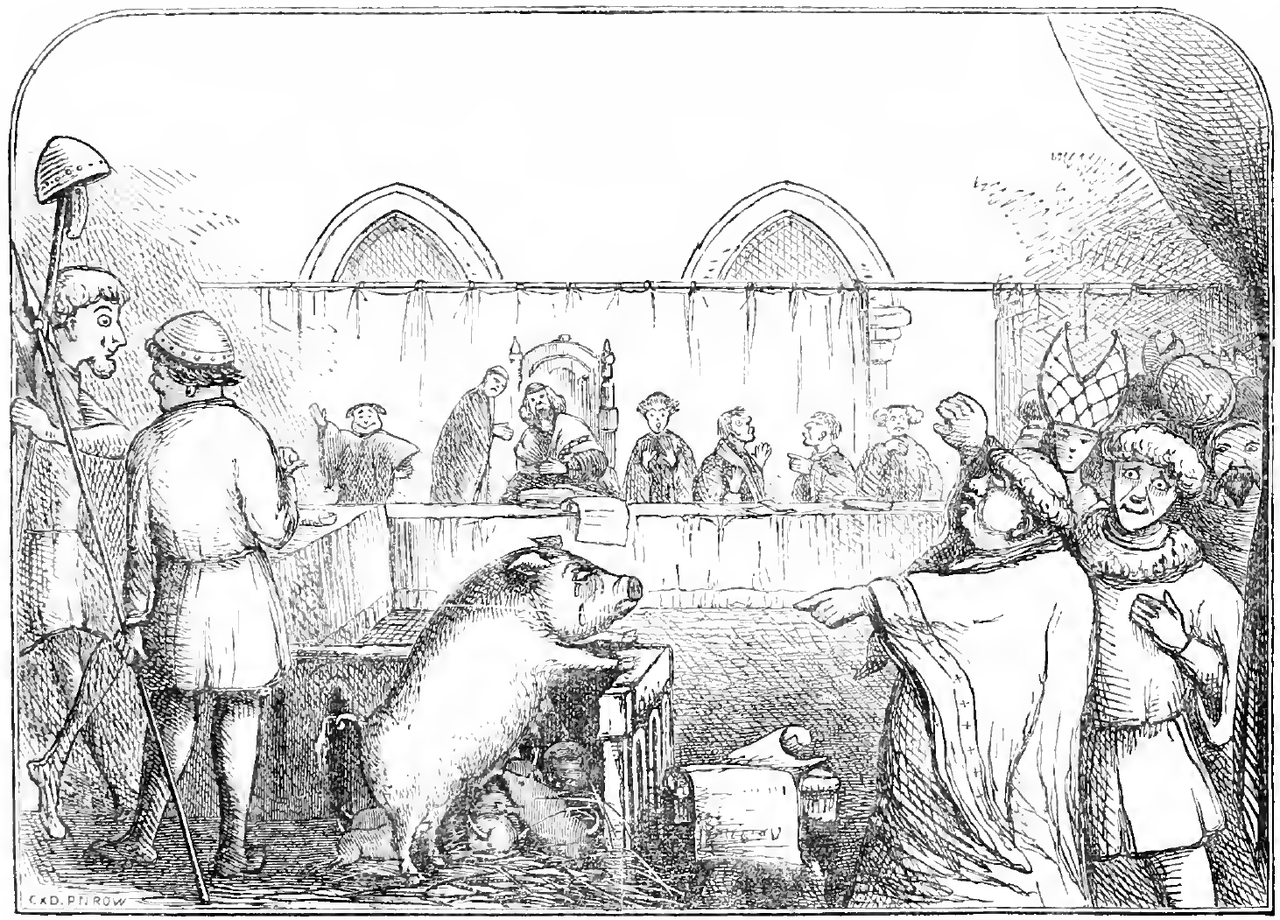

The book of miscellaneous events was published in 1869.

In an essay at Psyche, Ed Simon, a journalist who investigates the eclectic, looks at the history/mythology of trying animals like pigs and rats for criminal offenses. He sees an opportunity there for animal rights activism:

Dismissing animal trials as just another backwards practice of a primitive time is to our intellectual detriment, not only because it imposes a pernicious presentism on the past, but also because it’s worth considering whether or not the broader implications of such a ritual don’t have something to tell us about different ways of understanding nonhuman consciousness, and the rights that our fellow creatures deserve. From our metaphysics, then, can come our ethics, and from our ethics can derive politics and law. There need not be a return of animals to the stand as defendants, but they’ve already had legal representation as plaintiffs. The Nonhuman Rights Project, led by the US attorney Steven Wise, has filed briefs on behalf of creatures such as the four captive chimpanzees Tommy, Kiko, Hercules and Leo in New York in 2013, and more recently Happy the elephant, a solitary pachyderm at the Bronx Zoo.

Ed Simon, “If animals are persons, should they bear criminal responsibility?” at Psyche (December 21, 2022)

The key word here is “plaintiffs” — not “defendants.” There is a rather large gap there. One is the animal rights activists’ drive to gain control of animal welfare policy and the other would mean assigning blame to an animal for crimes, as understood by humans. Simon makes clear further in his article that he envisions animals as plaintiffs:

Today, the Nonhuman Rights Project (NhRP) is dedicated to the belief that certain animals deserve an acknowledgement of bodily integrity, among other positive rights, by dint of both their ability to feel pain and their obvious consciousness, which Wise believes indicates a degree of ‘personhood’. The NhRP has attempted to rectify through the court system what they view as injustices committed against animals, and to hopefully set a precedent for acknowledging their legal rights. All of the aforementioned filings had at their core an argument that the animals in question should be granted a degree of autonomy; that, as conscious beings, as demonstrated by certain cognitive tests, their oftentimes extreme restrictions were fundamentally inhumane, and thus illegal.

Ed Simon, “If animals are persons, should they bear criminal responsibility?” at Psyche (December 21, 2022)

If the goal had simply been to end inhumane practices in the conventional sense, that is covered under current statutes in New York. The activists are seeking a legal regime in which animals are recognized as “persons” with humanlike rights — hence the “Nonhuman Rights Project.” Of course, the animals will always be proxy “plaintiffs,” never defendants.

Some scholars defend the idea that animals have moral responsibility. For example, A 2018 paper announces, “It has been argued that some animals are moral subjects, that is, beings who are capable of behaving on the basis of moral motivations (Rowlands 2011, 2012, 2017). In this paper, we do not challenge this claim. Instead, we presuppose its plausibility

in order to explore what ethical consequences follow from it.” Sure enough, the authors conclude that humane legislation (they call it “welfarism”) will not work and that “beings who are moral subjects [animals] are entitled to enjoy positive opportunities for the fourishing of their moral capabilities, and that the thwarting of these capabilities entails a harm that cannot be fully explained in terms of hedonistic welfare.” Cue animal rights activists.

From a 2019 paper in the American Philosophical Quarterly: “I conclude that though it may be difficult to engage in the practice of holding animals morally responsible, given the communication barrier and lack of mutual understanding, some animals nevertheless act in ways for which they are morally responsible.”

A 2020 entry restricts the options in claims about moral capacity in animals: “So, if we wish to avoid talking at cross-purposes or wasting our time with merely terminological disputes, we should stop asking whether animals are “moral” or “proto-moral”. Better, I suggest, to focus on more fine-grained questions about what different species can do, what psychological mechanisms underlie their behaviour, and what philosophical implications may follow from this.” Notice, the choice is now between “moral” and “proto-moral”…

Back in 2006, a bioethicist claimed, “If the arguments of this paper are sound, many nonhuman animals manifest degrees of moral agency. Virtues such as compassion, courage, and loyalty provide the foundation of moral behavior, and are more important than mastery of abstract principles. Since many animals are capable of moral and immoral action, they are also subject to varying degrees of obligations, both positive and negative.” Of course the arguments aren’t sound! Apart from the “mastery of abstract principles,” there is no moral behavior; there is only the unaccountable inclination to do this or that. Once we start to account for our decisions, we are into abstract thinking.

There is more than a whiff in all this of sleight of hand. First, we can be pretty sure that, whatever claims are made for animal moral reasoning, the animals will not and cannot have independent agency. They are props that help form and flex the growing power of the animal rights movement that holds their “proxies” — a movement that is not likely to demonstrate much enthusiasm for human rights.

And, as we might expect, animal morality is a tap that can be turned on or off as needed. For example, freelance journalist Raegan Scharfetter looked recently at a review of information around cannibalism in bears in Ursus, a journal devoted to research on bears. We are urged to avoid moral judgment and put everything in context:

“Often the public would see a bear eating another bear as gruesome or immoral in a way, but bears are just out there living their lives, trying to survive,” [Miha] Krofel says. “So, if there’s a carcass that’s available, they just take the opportunity to eat it.”

Raegan Scharfetter, “It’s a Bear-Eat-Bear World: Understanding Cannibalism in the Largest Land Carnivores” at The Scientist (July 20, 2022)

Very well. But can we begin by admitting that the bear cannot ponder the significance of being a bear? That matters if we are trying to assess abstract qualities like “immoral in a way.” This isn’t ritual cannibalism, after all; the bear just doesn’t and can’t care.

Krofel’s traditional science perspective — understanding the ecology role ursine cannibalism plays — works fine so long as we are not also claiming that the bear makes moral choices. But then, I wonder whether, at bottom, the animal activists really believe that it does. Claims that animals are morally responsible help to undermine the sense of human moral responsibility while making no difference to the animals. That will, in the long run, further their aim of gaining power over other humans by holding the unwitting animals’ “proxies” and representing them in court cases.

It’s fashionable. But this will not be a better world if they succeed.

You may also wish to read: Do animals, as well as humans, have free will? One can make a case for animal free will in the strict sense that no life form is bound by complete determinism because it doesn’t exist. But if researchers are not talking about consciousness, morality, or responsibility, they are not talking about what humans mean by free will anyway.