Philosophy: Can Red Have “Redness” If No Self Perceives It?

As Closer to Truth’s Robert Kuhn interviews philosopher Julian Baggini, they now tackle the question of “qualia” — part of the nature of conscious experiencesYesterday, we looked at philosopher Julian Baggini’s argument that the unified self is an illusion. He spoke about this in the context of a discussion with Closer to Truth’s Robert Lawrence Kuhn. Kuhn, nearly midway through, steers the conversation toward qualia, that is, the inner experience we have of things.

Red, an often-used example, is a color in the spectrum but it is also, for many, an experience. Serious and influential books have been written (2005 and 2017) about the history of the color and the experiences it evokes. Questions are interspersed between exchanges in the transcribed dialogue:

Robert Lawrence Kuhn: (3:23) Let’s distinguish two factors that are flying around here. One is the concept of self — what it means to be yourself — the other is what does it mean to have these inner feelings, this sense of the red of redness and the sweetness of chocolate or whatever, where, whatever we’re feeling at the time, there’s this inner perception, so-called qualia as psychologists and philosophers call it. How do you differentiate those and how does your explanation fit either one well?

Julian Baggini: (3:57) To be honest, I mean there are lots of levels of detail here which I think we just don’t understand yet. I mean how it is that this sludgy stuff in our skulls gives rise to actual feelings and sensations, tastes, colors, we don’t understand properly yet. There’s no point pretending that we do.

Kuhn: (4:16) So if we are not able to understand things, of course, science always progresses. The problem with qualia, the inner feeling, is that even neuroscientists don’t even have a concept of what an explanation might even be like, because you have this brain, neurons, electrical activity in the brain and these internal feelings — and, in linking the two, no one even has a theory of what a theory could be.

Baggini: (4:47) Well, you know I think that could be right. I mean, our state of knowledge about these things is very limited. But I think what we have to remember is, if we look back at past mysteries, what counts as an explanation in the end? Now think about electricity or something like that. (5:03)

I think about life as a good example. People wanted, you know, you need something to explain life. You need some kind of life force or life principle. It turns out that when you have a sufficiently rich understanding of how cells, atoms, and interaction everything, you reach enough of an understanding about how things can replicate and so forth that there doesn’t seem to be a mystery anymore.

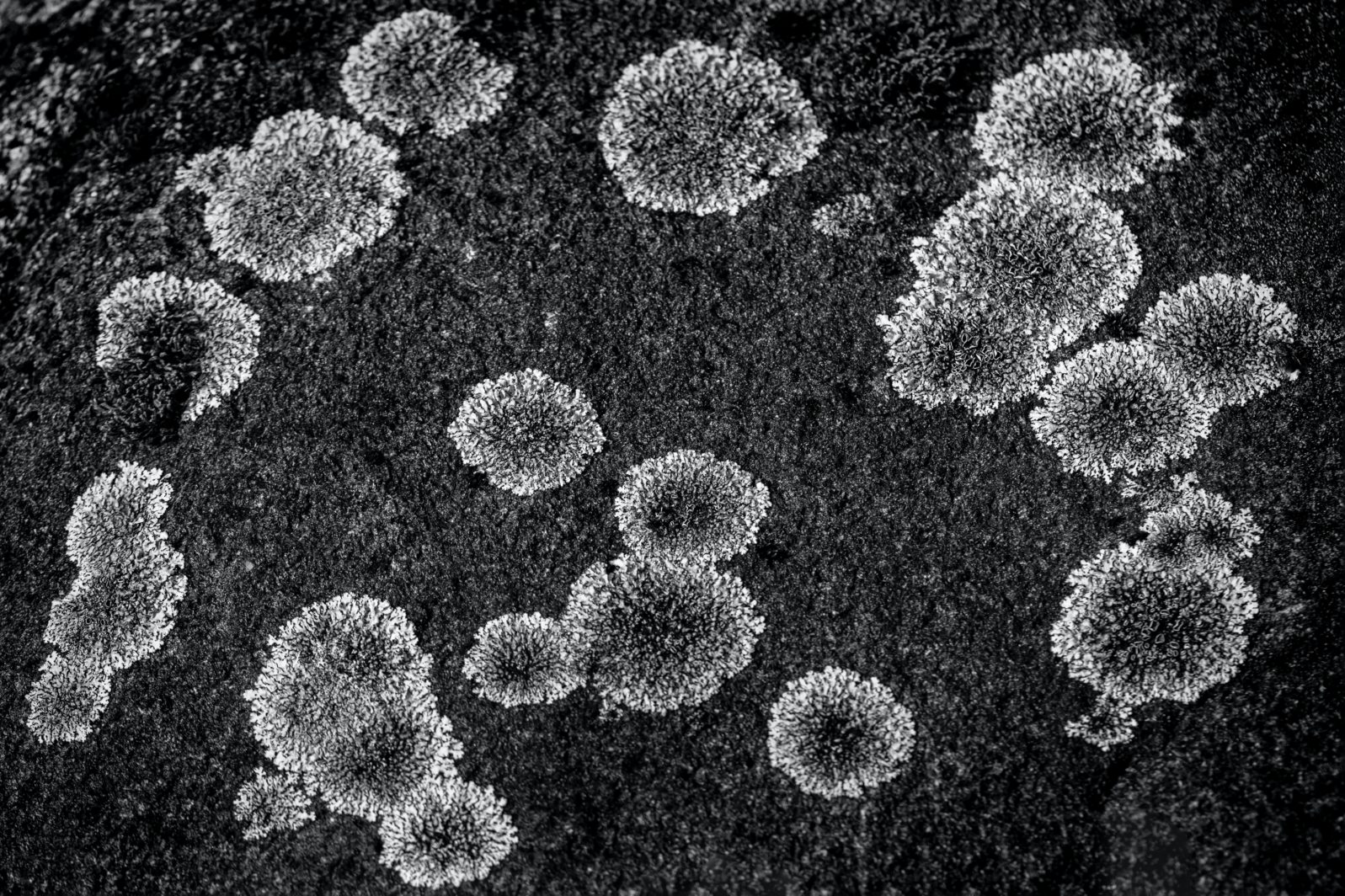

Question: Wait. Origin of life (“things can replicate”) is up there with origin of consciousness (of which qualia are a part) as a topic for which there are many contested hypotheses. True, we have a clear idea what life is. That is, we can say with confidence that lichens are alive and rocks are not. We can clearly identify the “living” qualities that distinguish lichens from rocks. But origin of life is a historical event, a moment in time, and we really don’t know what happened then. If “there doesn’t seem to be a mystery anymore,” you would not know it from the vast literature on the topic.

Baggini: Go dig deep enough, there still is a mystery. You know, I mean electricity (5:28) … I know people who are scientists who say, actually, if I think about it I don’t really understand how electricity works. Like, you know, we have equations which tell us which forces are operating and so forth. (5:49) We have models but how? why? You can only dig so deep.

Question: Dr. Baggini’s thoughts on electricity respond to Kuhn’s comment at 4:16: With subjects like qualia, “no one even has a theory of what a theory could be.”

We think we know what a theory of electricity could be. Yet scientists have been willing to tell Dr. Baggini, “I don’t really understand how electricity works.”

That is hardly due to their ignorance of the topic! To the extent that electricity depends on quantum mechanics, it originates in a world that we perhaps can’t know. That is, it may be that we can’t make how electricity works coincide with our expectations for a proper explanation. We must then be content to merely say what it is.

But shouldn’t this level of uncertainty even about electricity (by which neurons communicate) cause us to wonder whether we are looking in the right places for answers to more complex questions like how we should understand qualia?

Baggini: So my suspicion is that as we get a richer understanding of how the different systems of the brain work and so forth we’ll reach a level of understanding and explanation which will do. And if people want to then insist that there is still a deep mystery (“Yes, but how is it that we feel these things?”), you could say the same things of “Yes but this is there still a deep mystery about how things can be alive, how something can replicate and so forth.”

Question: But does Dr. Baggini really want to be where this takes us? As noted earlier, we are deadlocked about the origin of life. And electricity takes us down into the world of quantum mechanics where certainties are not even an aspiration. Why do we think we will reach “a level of understanding and explanation which will do” when we are talking about much less certain topics like qualia?

Kuhn: (6:07) So do you have every confidence that there will be a physical explanation for the inner sense of awareness, this concept of qualia in consciousness?

Baggini: (6:16) I’m agnostic about how we’re going to go with being able to explain feeling, sensation, qualia, scientifically. I just don’t think we know. I think a lot of people are being too confident in saying science can never explain this or science will explain it. You know there are going to be limits to our knowledge. I think that’s something we all have to accept. (6:36)

I think what’s quite curious here in these kind of debates — particularly about people who will point to the absence of an explanation, a scientific explanation, of qualia as some kind of evidence for the need to plug that gap with the religious truth — is that, you know people will appeal to the ineffability of certain things or the mystery of things to suit them. So, you know, people who are happy with God being mysterious in all sorts of ways are not happy with consciousness being mysterious in all sorts of ways.

Question: God — whether people believe in him or not — is, by definition, a supernatural being. What we can’t understand about God may then be outside of nature. If we simply can’t come up with a scientific explanation of qualia, why isn’t the best explanation this: that some elements of consciousness also lie outside of nature?

Baggini: (7:04) And similarly, you know, there are some sort of materialists who sort of don’t accept the fact there might be limits to our knowledge. There are bound to be limits to our knowledge. Look at us, we’re just overgrown apes or undergrown apes, actually.

Question: Is not the fact that we are having these discussions the best available evidence that we are not “just overgrown apes or undergrown apes”?

And if it is true — as the Smithsonian advises — that our genomes differ from those of chimpanzees by a mere 1.2%, why is it not reasonable to assume that the explanation for the difference humanity makes lies outside the material world?

Baggini: (7:22) People’s tolerance for mystery seems to be very, kind of, selective. So there are people who are perfectly willing to accept the mysteries of God and the divine but who look at the gaps in current science and say, well, science can’t explain that. We’ve got to plug it with something else.

At the same time, there are perhaps some scientists, materialist philosophers, who are just too confident that you know we’re going to have a physical explanation for everything. I think it’s perfectly conceivable that there are limits to human knowledge, to human understanding, and that we just won’t be able to fully understand some things.

But I think we should be agnostic about that at the moment. We don’t know how successful we’re going to be. We have to give it time.

Question: Is there no difference between the mysteries of God and gaps in science? As noted above, we can’t know anything about a supernatural being that he does not choose to reveal; thus the founding stories of theistic religions are stories of divine revelation. Gaps in science, by contrast, may or may not be fillable for a variety of reasons. With origin of life, the information may now be permanently lost. Electricity may prove intractable for the sort of explanation that the inquirer seeks if the quantum world is involved. If consciousness is not a material thing, it may not be explainable in the terms we use to explain material things. So, a final question: If scientists and philosophers cannot accept that last possibility — that consciousness is not a material thing and does not originate in the material world — why can’t they?

Here’s the earlier post on the discussion between Baggini and Kuhn: Another philosopher argues that the unified self is an illusion. At Closer to Truth, Lawrence Kuhn interviews Julian Baggini, who claims, in terms reminiscent of Thomas Metzinger, that a unified self is an illusion. On behalf of Mind Matters News, I listen and ask some questions about just how the enduring self — the thing we are most sure of — could be an illusion.

You may also wish to read: A British philosopher looks for a way to redefine free will. Julian Baggini’s proposed new approach assumes the existence of the very qualities that only a traditional view of the mind offers. Baggini discounts the importance of quantum mechanics and believes that neuroscience disproves free will; he is wrong on both counts.