How a Theory of the Soul Drives Abortion Activism

Descartes’ theory that the soul and the body are utterly distinct, while mostly rejected in philosophy, is still part of popular culture

Every now and then, it’s useful to look at the philosophical underpinnings of current thought and what implications they have for engineering ethics. In a recent post on the website of the journal First Things, professor of biblical and religious studies Carl Trueman noted that Cartesian dualism — a way of looking at the human person promulgated by René Descartes (1596-1650) — is enjoying a comeback in the popular mind, although modern philosophy has long since discarded it as an inadequate model.

(This article by Karl D. Stephan originally appeared at Engineering Ethics Blog (October 11, 2021) under the title “Against Cartesian Dualism,” and is reprinted with permission.)

If you know anything about Descartes, you will probably recall his most famous saying: “I think, therefore I am.” He arrived at that conclusion after discarding everything he could think of that might possibly not be true — the evidence of his senses, things he knew on authority, and so on. Whatever else might be false, he reasoned, he couldn’t help thinking that he was still thinking, and therefore there must be a thinker somewhere. He was so impressed by this idea that he developed a whole philosophy around it, which came to be known as Cartesian dualism.

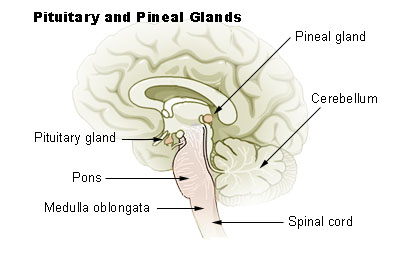

Descartes believed that the soul — which in modern terms pretty much amounts to what we would call the mind —was a “spiritual substance” that was immaterial, without dimensions or location. And the body he believed to be completely material, an entirely separate substance from the soul, consisting of the brain, the nerves, the muscles, etc., all of which operate under the control of the immaterial mind and will. As to exactly how the immaterial controlled the material, Descartes wasn’t sure. But he thought the point of contact might be the pineal gland, a small pine-cone-shaped gland near the middle of the brain.

Modern science has discovered that the pineal gland, far from controlling the entire body, mainly secretes melatonin, which affects sleep patterns—but that’s about it. And modern philosophy has discarded Cartesian dualism, because nobody after Descartes was ever able to show how a completely immaterial thing like Descartes’ hypothetical soul could affect a physical thing like the body.

But this news evidently hasn’t reached a lot of women athletes who submitted an “amicus” (friend of the court) brief to the U. S. Supreme Court, urging the court to uphold abortion rights in the upcoming Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization case, in which the State of Missouri is seeking to overturn Roe v. Wade, the decision that made abortion legal in the U. S.

As Trueman observes, the women in the amicus brief speak of their bodies as nothing more than sophisticated tools or instruments, operated by their minds and wills. They say that they “depend on the right to control their bodies and reproductive lives in order to reach their athletic potential.” If we stop with only that quotation, we can see that (a) the operative verb is “control” and (b) the purpose of controlling the body is to “reach their athletic potential.”

In other words, for these women, their body is a means to the end of achieving success in athletics, just as a fast race car is a means to achieving success in the Indy 500. And prohibiting abortion is like compelling a race-car driver to give a ride to a 300-pound hitchhiker during the race.

Cartesian dualism shows up in lots of places these days outside of law courts. The whole transhumanist movement, of which famed entrepreneur Elon Musk is a proponent, is based on the idea that the real you is basically a software program running on the wet computer called the brain. The phrase “meat cage” that some people use to describe the body partakes of this same idea—that we are not our bodies, but that we use our bodies in a way not much different in principle than using a car or a computer.

Perhaps the most pernicious feature of Cartesian dualism is the temptation to assess the humanity or non-humanity of other people based on our judgment as to whether they have a mind worthy of the name. I would imagine it is easier to contemplate an abortion if you believe the fetus in question has not developed a mind yet. And the same goes for people who are mentally disabled, suffer from Alzheimer’s disease, or are otherwise incapacitated to the extent that their minds no longer control their bodies adequately. Perhaps it’s just as well to sever the connection between the mind and the body if the mind can’t do its job controlling the body any more.

Well, if Cartesian dualism isn’t true, how should we think of the relation between the mind and will (or soul, to use the more old-fashioned term) and the body? The model of the person Descartes was trying to displace is called hylomorphism, originated by Aristotle. Philosopher Peter Kreeft explains that Aristotle’s theory considers the body to be what the person is made of, and the soul as the form or molding and patterning influence of the body. So matter (Greek hyle) is “informed” by form (morphe) to create one integral thing with two aspects or causes: the material cause, namely the body, and the formal cause, namely the soul. But the human person is one unique thing, not two.

If hylomorphism was more popular than Cartesian dualism, I think we would see a lot of salutary changes in everything from attitudes toward the life issues (abortion, euthanasia, etc.) to medical and surgical procedures (sex-change operations, transhumanist initiatives) and even tattoos. If you thought you were hiring a tattoo artist to burn an image of some hip-hop star on your very being, instead of just some piece of machinery you happen to be living in now, you might think twice before doing it.

But the spirit of the age favors Cartesian dualism. As consumers, we are urged to treat the rest of the world as a selectable, disposable warehouse of products and services—why not treat our bodies the same way? I’m glad that my university is a rare holdout among public institutions of higher education for continuing to require that all its undergraduates take at least one philosophy course. In such a course, they stand a chance of hearing about Cartesian dualism and why it is no longer respectable. And they might even take what they hear in class seriously, and apply it to their lives. Such a hope is all that keeps some educators going.

Sources: Carl Trueman’s article “The Body Is More Than a Tool” appeared on the First Things website at https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2021/10/the-body-is-more-than-a-tool. Elon Musk’s promotion of transhumanism is described at https://futurism.com/elon-musk-is-looking-to-kickstart-transhuman-evolution-with-brain-hacking-tech. Peter Kreeft demolishes Cartesian dualism (and a lot of other false philosophical ideas) in his book Summa Philosophica (St. Augustine’s Press, 2012). I also referred to the Wikipedia article on hylomorphism.

You may also wish to read: Do babies really feel pain before they are self-aware? Michael Egnor discusses the fact that the thalamus, deep in the brain, creates pain. The cortex moderates it. Thus, juveniles may suffer more. Jonathan Wells recalls, from when he was a lab technologist, how very premature infants would scream when he took a drop of blood for tests.