A Wrinkle In Time: Reading Science Fiction At An Early Age

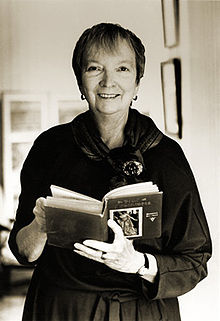

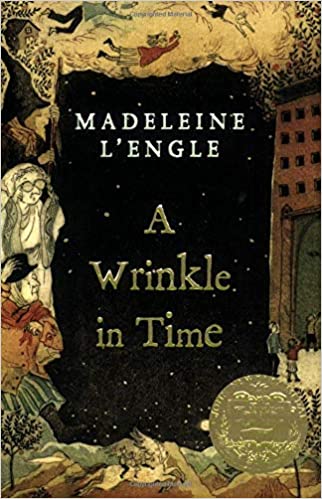

An early introduction to science fiction will be a boon to any child's imaginationWhen I was young, my father was constantly pressing new books into my hands. The first in remembrance was C.S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe. The second to stand out was Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle In Time.

It was a funny choice, really. My father’s theology does not match L’Engle’s universalism, nor are his preferred subjects math and science. At the time, I was unable to wrap my mind around concepts of dimension and time introduced by L’Engle, but the novel became a fast favorite that I have returned to in my adulthood.

A Wrinkle In Time was most recently brought back into popular view when an adaptation imagined by director Ava DuVernay was released in theaters in 2018. The film was visually satisfying, but ultimately, among other faults, the story was robbed of its charm and the way L’Engle introduced young children to complex scientific concepts.

In one chapter, for instance, celestial creatures acting as guides explain to the protagonist young children on a galactic quest to find their lost father the concept of dimensions and time/space travel through the imagery of an ant traveling across a straight line:

“You see,” Mrs. Whatsit said, “if a very small insect were to move from the section of skirt in Mrs. Who’s right hand to that in her left, it would be quite a long walk for him if he had to walk straight across.”

Swiftly Mrs. Who brought her hands, still holding the skirt, together.

“Now, you see,” Mrs. Whatsit said, “he would be there, without that long trip. That is how we travel.”

Madeleine L’Engle, A Wrinkle In Time

The supernatural guides explain to the children the differences between the first, second, third, fourth, and fifth dimensions. Einstein is briefly introduced along with his theory of space-time.

In one frightening scene shortly following, the guides mistakenly transport the children to a two-dimensional planet. L’Engle’s descriptions of a third-dimensional creature being forced to conform to the laws of a two-dimensional world (“as though she were being completely flattened out by an enormous steam roller”) leaves an unforgettable impression on the young reader.

L’Engle’s story (the first in a quintet) is filled with early introduction to philosophy, religion, math, and science. She does so in a way that is not overwhelming to the young reader, but peaks their interest and stokes their curiosity.

An early introduction to science fiction has been a boon for my own curiosity and wonder. In high school, biology was my worst subject. In college, it remained a struggle. A Wrinkle In Time encouraged me to not give up on scientific curiosity, despite the fact that I would never succeed as a proper scientist.

Since then, I have been able to slowly feed the hunger given me by L’Engle’s science fiction exploration. I have been inspired by books such as William J. Kauffman’s Relativity and Cosmology, Paul Davies’ About Time, and Stephen Hawking’s A Brief History of Time. Stephen Meyer’s Return of the God Hypothesis is my next reading venture.

It is with the science fiction images of Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Who, and Mrs. Which, of Meg and Calvin and Charles Wallace, and of the journey from a safe and comfortable New England village to a dystopian planet on the outskirts of another galaxy that have inspired my continued investigation into the innumerable discoveries that (non-fiction) scientific exploration provides.

I am sure others have far more profound things to say than I on the importance of stoking wonder within the imaginations of children through the stories and education provided them. What I know is of my own experience, and the immeasurable good it was for me at a young age to be introduced through story to the complex wonders of the world in which we live.

Forget the movie. Press this book into your child’s hands as my father pressed it into mine.