Mystery: Our Brains Divide Up Events But We Experience Them Whole

That’s one of the conundrums of consciousnessIn the third podcast of the series, “Unity of Consciousness,” Walter Bradley Center director Robert J. Marks interviews Angus Menuge, professor and chair of philosophy at Concordia University, on some of the unique features of human consciousness, starting with its unity.

This portion begins at 01:04 min. A partial transcript, Show Notes, and Additional Resources follow.

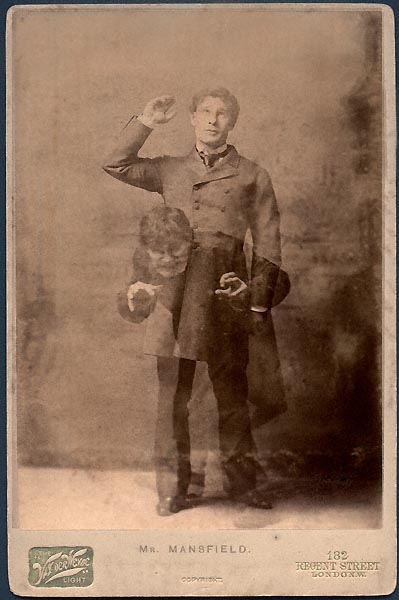

Robert J. Marks: We hear of “Dr. Jekyll–Mr. Hyde” dual personalities but most of us only have one consciousness. What is the so-called unity of consciousness? It’s an area in philosophy, is that right?

Angus Menuge (pictured): Going back a very long way. It’s mentioned by Plato and Aristotle, and later on by Kant… We can have many experiences concurrently. So when you see a sunset, you hear the whooping of cranes going by, you smell the aroma of coffee, and you feel the wind going through your hair. And yet all of those are unified in one conscious field. So it’s not as if there is one consciousness witnessing the sunset, another consciousness hearing the cranes, another one feeling the wind, another one smelling the coffee. No, they are all experiences metaphorically located within one field of consciousness.

And this problem has become even more remarkable as we know more about the brain because we now know that the brain is highly distributed. It’s a parallel distributed system. And we know that, even with just one object — a blue bull that’s bouncing — the part of the brain concerned with color and the part of the brain that’s concerned with shape and the part that’s concerned with motion are all different. And yet we integrate that and we are conscious of one object. So there’s a unity, both in the sense that many experiences belong to one consciousness but also that we experience objects and activities as integrated wholes within that experience.

Note: Scottish writer Robert Louis Stevenson (1850–1894) wrote a short horror novel about a scientist, Dr. Jekyll, who had discovered a way “to transform himself periodically into a deformed monster free of conscience — Mr. Hyde.” Trouble was, after a while Jekyll couldn’t control the process any more. The story (online) became a metaphor for split consciousness. Note: The photograph (1895) depicts an actor playing both characters in a stage play, using double exposure.

Next: How split-brain surgery underlines the unity of consciousness

You may also wish to read: Yes, split brains are weird, but not the way you think. Scientists who dismiss consciousness and free will ignore the fact that the higher faculties of the mind cannot be split even by splitting the brain in half.

Show Notes

- 00:30 | Introducing Dr. Angus Menuge

- 01:04 | Unity of consciousness

- 03:04 | Split-brain operations

- 04:55 | Split personalities

- 06:49 | Too many thinkers problem

- 11:06 | Why don’t bodily changes generate a different consciousness?

- 14:28 | Elon Musk’s Neuralink

Additional Resources

- Dr. Angus Menuge at Concordia University

- The Inherence of Human Dignity, vol. 1: Foundations of Human Dignity edited by Dr. Angus Menuge

- The Inherence of Human Dignity, vol. 2: Law and Religious Liberty, edited by Dr. Angus Menuge

- Religious Liberty and the Law, edited by Dr. Angus Menuge

- The Blackwell Companion to Substance Dualism, co-edited by Dr. Angus Menuge

- Michael Egnor at Discovery.org

- Tim Bayne, philosopher of mind and cognitive science

- Sybil (1976)

- Richard Swinburne, English philosopher

- Neuralink

- Elon Musk, entrepreneur and engineer