Did Social Media Panic Drive Up the Damage from COVID-19?

Richards: It was, honestly, terrifying to watch important stories and studies get buried in real time on Google searches.

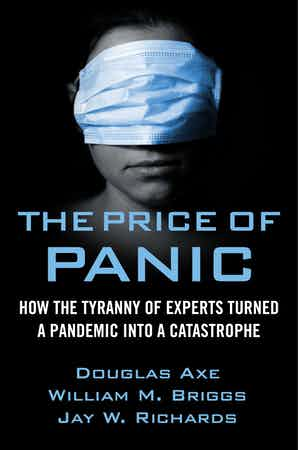

Last month, business studies prof Jay Richards, along with co-authors Douglas Axe and William M. Briggs, published a book with some controversial premises: One of them is that many popular COVID-19 fears are the overblown outcome of paying too much attention to social media as opposed to the facts that got lost in the uproar. And that we are paying the price now in human, as well as financial, costs.

The Price of Panic: How the Tyranny of Experts Turned a Pandemic into a Catastrophe (October 2020) assembles a massive statistical case. But in this interview with Mind Matters News, Richards focuses on how it affected us: What we all thought was happening and why we thought so—a different story from the statistics in many cases.

Mind Matters News: What do you make of WHO’s recent about-face on lockdowns? (October 10, 2020): “Dr. David Nabarro said to The Spectator’s Andrew Neil. ‘The only time we believe a lockdown is justified is to buy you time to reorganize, regroup, rebalance your resources, protect your health workers who are exhausted, but by and large, we’d rather not do it.’”

Jay Richards: As we discuss in the book, WHO published an October 2019 report on the scientific literature, and concluded that population-wide lockdowns, as well as masks and other mitigation efforts that became popular in 2020 were unlikely to make much difference. It also noted that the social costs of lockdowns would be very high.

That evidence didn’t change in March 2020. Instead, WHO jumped on the bandwagon. So, when Dr. Nabarro offered his misgiving about the value of lockdowns, he was actually returning to WHO’s original assessment of evidence, before everything went crazy in 2020.

Mind Matters News: You mentioned that SARS (2003), while deadly, did not produce an immensely costly uproar like COVID. Would more people have had a more realistic picture of the COVID crisis if social media did not play so big a role in our lives now? If so, in what way?

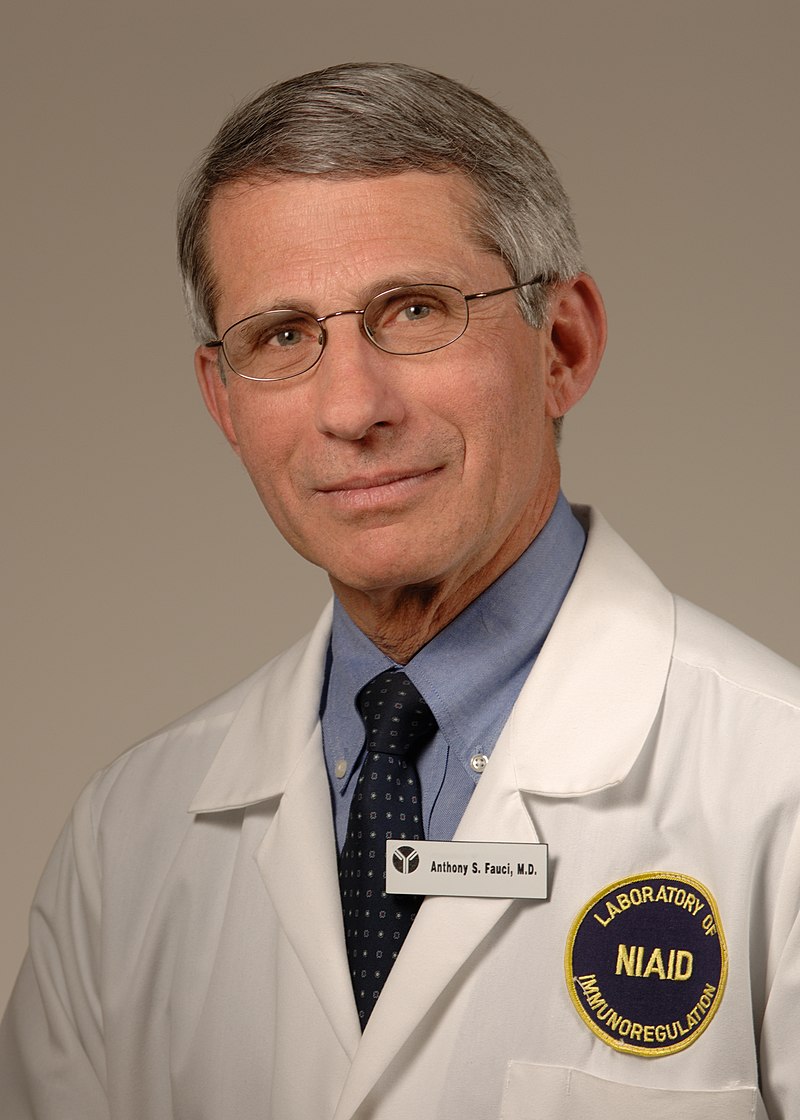

Jay Richards: (pictured) In working on the book, we watched social media and platforms such as Google Search manipulate news coverage of the pandemic. It was, honestly, terrifying to watch important stories and studies get buried in real time on Google searches. It was also distressing to watch Twitter and Facebook attach warnings to the advice and viewpoint of scientists who urged calm and caution, while boosting the views of “officials” such as Anthony Fauci and WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom.

That said, the problem is not merely that social media play an important role in our lives. The problem is that the media and social media boosters all opted for a narrative of panic. In July, the COVID tracking poll revealed that the average American thought 9 percent of the US population had died from COVID-19. The real number was about 0.06 percent. So Americans thought the coronavirus was 150 times more deadly than it actually is.

Now, where did they get that impression? People were not reading PubMed or checking the tables at the CDC COVID-19 website. They were getting that from their newsfeeds. The media decided for a variety of reasons—some good, some benign, some bad—that it would be best to panic the population. And they did a very good job of it.

Mind Matters News: Okay. Is there an underlying need for panic that social media exacerbate? For example plummeting numbers of deaths today tend to go unnoticed in the wake of news breakouts about new “cases”—which are not at all the same thing. The number of people responding to the panic anyway suggests that it is meeting a need that facts would not. Do you have any thoughts on what that need might be?

Jay Richards: I think there is a natural incentive for media, especially now that social media stands between media outlets and most consumers, to sensationalize. Nobody will click on a story about how almost all Americans that were alive yesterday are still alive today. News is only interesting if it’s unusual. The problem is that we—the consumers of media—have not trained ourselves to discount what we see and hear from the media, based upon this basic fact of incentives.

But of course, the media have always had such an incentive, so why was it different this time?

I think the sheer speed and immediacy of social media played a crucial role. Only in the last few years could a random picture of an elderly man falling dead on a street in China be seen, within hours by hundreds of millions of people around the world. This allows extremely rare outlier events to get captured and shared, so that, if we’re not careful, we might mistake an extreme outlier event for a representative event.

I don’t think our brains are adapted for this. Our technological prowess is outstripping our capacity to adapt to it. If we’re going to avoid planet-scale social contagions in the future, like we’ve experienced in 2020, we’re going to have to learn how to filter the information coming from social media. The first step in doing that is for everyone to realize this is a serious problem.

Mind Matters News: We’ve seen how wholly incorrect statistical models have prompted panicky decisions at high levels—even though the potential for the models to be wrong was apparent. Would it be fair to call this a sort of “superstition” of science, in the sense that we are asked to “trust the science” while evidence-based reasoning is avoided? Why might Big Science today be prone to this type of thinking?

Jay Richards: There’s definitely a sort of magical thinking that is attached to the predictive power of models. In theory, there’s nothing wrong with a model, as long as you recognize what it is. It is, in effect, a complex argument run on a computer, that is based on certain assumptions (or “propositions”). But the model is only as good as its assumptions.

A model that is not validated against the real world—against real scientific evidence—is just speculation. Unfortunately, modelers have a tendency to treat their models as if they were evidence. And the media, which is profoundly gullible on these sorts of things, takes that at face value. This is the only way the model from Imperial College London could have gained the power to shape a global public health response.

We need to separate untested predictive modeling from politics if we’re going to avoid this in the future. And the public needs to learn the difference between data and evidence on the one hand, and speculative modeling on the other. It does everyone a profound disservice to include both of these things under the rubric of “science.”

Your reference to Big Science is also important. From the very beginning, there were plenty of scientists urging caution, and criticizing the media’s favorite predictive models. But they were marginalized in favor of scientists who happened to be UN or government officials. Tedros and Fauci (pictured), for instance, were treated by the media as if they somehow spoke for science itself. But being a government official does not confer scientific wisdom or infallibility on someone. Getting a job in the administrative state is not like winning the gold medal of scientific smarts.

On all the major controversies during the pandemic—from its dangers to the wisdom of shutdowns—there was a lively scientific debate. But again and again, the “officials” were given authority over other scientists. This is a misuse of science.

Mind Matters News: You and your co-authors write, “We should do whatever we can to dismantle such experts’ unchecked power over public policy. These experts, however, could never have done so much damage without a gullible, self-righteous, and weaponized media that spread their projections far and wide. The press carpet-bombed the world with stories about impending shortages of hospital beds, ventilators, and emergency room capacity. They served up apocalyptic clickbait by the hour and the ton.”

Is there a sense in which traditional media have changed their role in society? There have always been sensationalist media, of course. But we seemed to be hearing panic from all of them, even though one can go directly to an official source on the internet for up-to-date information today. We would need the traditional media only if we needed a panic fix. Could you characterize what traditional media aim at becoming in the age of the internet and social media? What role do they want to play?

Jay Richards: Ideally, the media provide a check against those in power, and translate complex ideas for the public, so that the public is able to participate meaningfully in public life. This is certainly the vision behind the First Amendment in the US. Unfortunately, we now have media culture in which corporate media companies and Big Tech effectively collude with each other to maintain power, and to control the flow of information.

At the same time, it’s far easier for people who know how to do research to find information using the internet, social media, and search engines. My co-authors and I wrote our entire book while locked down in three different parts of the world. We just needed email, videoconferencing, Google docs, and access to the internet.

A carefully curated Twitter feed can be a powerful source of up-to-date information—even though Twitter does everything it can to manipulate what gets through. And very often, independent analysts, journalists, and experts provided far more accurate and lucid information on the pandemic than official media sources. If it hadn’t been for Twitter, we never could have found them.

So what exactly is the purpose of traditional media in this environment? It’s not to break stories, or do incisive analysis, or provide properly vetted information. More often than not, the so-called mainstream media was a source of misinformation and panic porn during the 2020 pandemic. What if, in an era of ubiquitous networks and social media, the main function of traditional media outlets is to shore up the interests of the powerful and to marginalize dissenters?

Note: Here are some other interviews with the authors, excerpts, and more information about the book.

For more on the dangers of taking computer models based on Big Data seriously, without understanding their limitations:

New book outlines the dangers of Big (meaningless) Data. Gary Smith, co-author with Jay Cordes of Phantom Patterns, shows why human wisdom and common sense are more important than ever now