Why Intelligent Women Marry Less Intelligent Men

Are they trying to avoid competition at home as well as at work? Or is there a statistical reason we are overlooking?When I read that Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s late husband was a wonderful man but less accomplished than his wife, I was reminded of “Ivy,” one of the most impressive students I ever had the privilege to teach. Ivy excelled in her coursework, won a prestigious scholarship for postgraduate study in England, went to a top-five law school, clerked for a Supreme Court Justice, and is now a law professor at a great university.

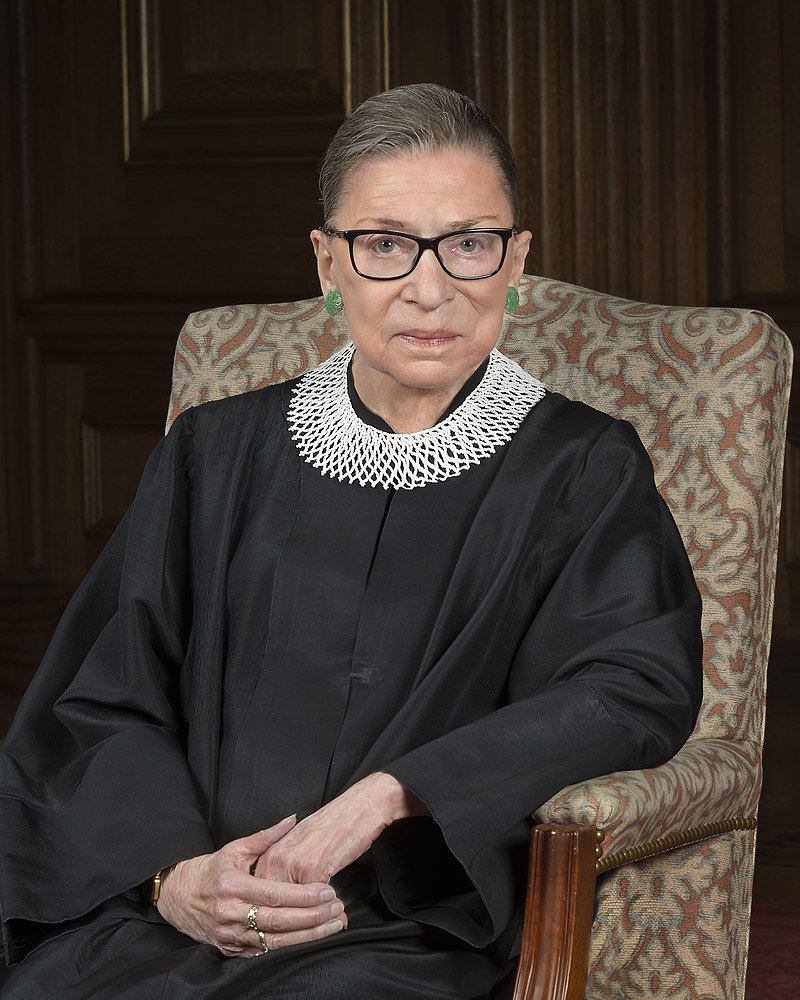

Like Ruth Ginsberg (1933–2020, pictured), Ivy married a man who is very nice but less intelligent than she. This is not an unusual situation. I made a list of the dozen most intelligent female students with whom I’ve kept in touch over the years. These women are all spectacularly talented but I estimate that two-thirds married men less intelligent than themselves. Their husbands are not dummies but they are not as impressive as their wives. On a scale of 1 to 10, the women are 10s and their husbands are mostly 7s to 9s.

Why is this? Are all-star women threatened by intelligent men? Do spectacular women want the upper hand in spousal debates? Do they need to feel superior at home as well as at work?

The most likely explanation is none of the above. Instead, we are assigning causes based on what has been called “one of the most fundamental sources of error in human judgment”: We fail to consider regression toward the mean. Let me explain.

When choosing mates, intelligence (no matter how it is measured) does matter because people generally enjoy the company of others of comparable intelligence. But intelligence isn’t the only thing that matters. Women may be attracted to mates who are caring, funny, athletic, sexy, share similar interests, whatever. The point is that a woman whose IQ is, say, 140 won’t restrict herself to soulmates with 140+ IQs and there are a lot more potential mates with IQs below 140 than above. So she will most likely choose someone with an IQ below 140. Similarly, a woman with an IQ of, say, 80 won’t restrict herself to mates with IQs of 80 and there are a lot more people with IQs above 80 than below.

To make the argument more pointed, consider this question: Why don’t women who have won a Nobel Prize marry only people who have also won Nobel Prizes? First, because they look for achievements other than Nobel Prizes in a future spouse’s resume. Second, because a Nobel Prize requirement would rule out virtually all potential mates.

So, even though intelligence matters, there is regression toward the mean in that women whose intelligence is far from the mean will, on average, choose spouses whose intelligence is closer to the mean. In particular, highly intelligent women tend to marry men who are less intelligent than themselves.

The pattern also holds for men’s spouses. Highly intelligent men also tend to have mates who are less intelligent than themselves for the same reason that highly intelligent women tend to have less intelligent spouses.

Is there any evidence beyond Ruth Ginsburg and Ivy? Well, it turns out that the Henry A. Murray Research Center of the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study has a collection of IQ test-scores for 43 women and their husbands, and these data confirm this regression toward the mean. The top quarter of the female IQs averaged 119 while their husbands averaged 109. At the same time, the top-quartile men averaged 117 while their wives averaged 107.

This seeming paradox of highly intelligent people marrying people who are not as intelligent is but one of many examples of regression toward the mean that we encounter all the time. Whenever we overlook such confounding factors, we are tempted to invent fanciful explanations when none are needed.

For instance, it has also been observed that the children of bright parents are typically not as bright as their parents and this observation invites a causal explanation. Perhaps geniuses are bad parents and their behavior depresses their children’s intelligence. Perhaps the children of the most accomplished people do not develop their own intellectual abilities because they fear that they will look bad in comparison to their parents. Maybe, but there is also the purely statistical explanation of regression toward the mean.

Because there is a positive, but imperfect, correlation between the intelligence of parents and their children, the children of the brightest parents tend to be above average, but not as far above average as their parents. And, again, there is regression in the other direction. The brightest children tend to have parents who are not as bright as themselves.

We can confirm this argument with the Murray Research Center data, which also includes the IQs of the children of these 43 married couples. I calculated the average IQ of each pair of parents and the average IQ of their children. The ten highest-IQ parents had an average IQ of 118 while their children had an average IQ of 111. The ten lowest-IQ parents had an average IQ of 76 while their children had an average IQ of 84. Parents whose IQs are far from the mean tend to have children whose IQs are closer to the mean and children whose IQs are far from the mean tend to have parents whose IQs are closer to the mean.

The regression argument applies to a very large number of other spousal and parental traits, including height, weight, athletic ability, health, age at death, creativity, empathy, kindness, and humor. You name it. No matter what the sex, exceptional people tend to have less exceptional spouses, exceptional parents tend to have less exceptional children, and exceptional children tend to have less exceptional parents. It also applies to friends and acquaintances. Thus highly intelligent people tend to have not only spouses but also children and friends who are less intelligent than themselves. Replace “intelligent” with almost any other trait, and the observed regression is still true.

Not only that, but the regression principle also holds across time for any single person, group of people, or event. Golfers who win a major tournament usually don’t win the next tournament. Students who get the highest scores on any test generally do not do as well on a second test. The most successful mutual funds in any given year are usually not as successful the following year. The most profitable companies in the past are generally not as profitable in the future. The most attractive job candidates often disappoint. The most promising medications are not as effective as promised. The sequels to great movies are generally not as good as the originals.

As my co-author on The 9 Pitfalls of Data Science Jay Cordes says, “Regression is the key to the universe.”

You may also enjoy these pieces by Gary Smith:

The stock market keeps rising despite COVID. Is it nuts? I’ve been asked whether advanced AI can explain the conundrum.

and

Female hurricanes: how a mass of hot air became a zombie study When a reporter first asked me about a study claiming that “Female Hurricanes are Deadlier than Male Hurricanes,” I was sceptical…