STEM EDUCATION 1. Pursuing Nerd Quality Over Nerd Quantity

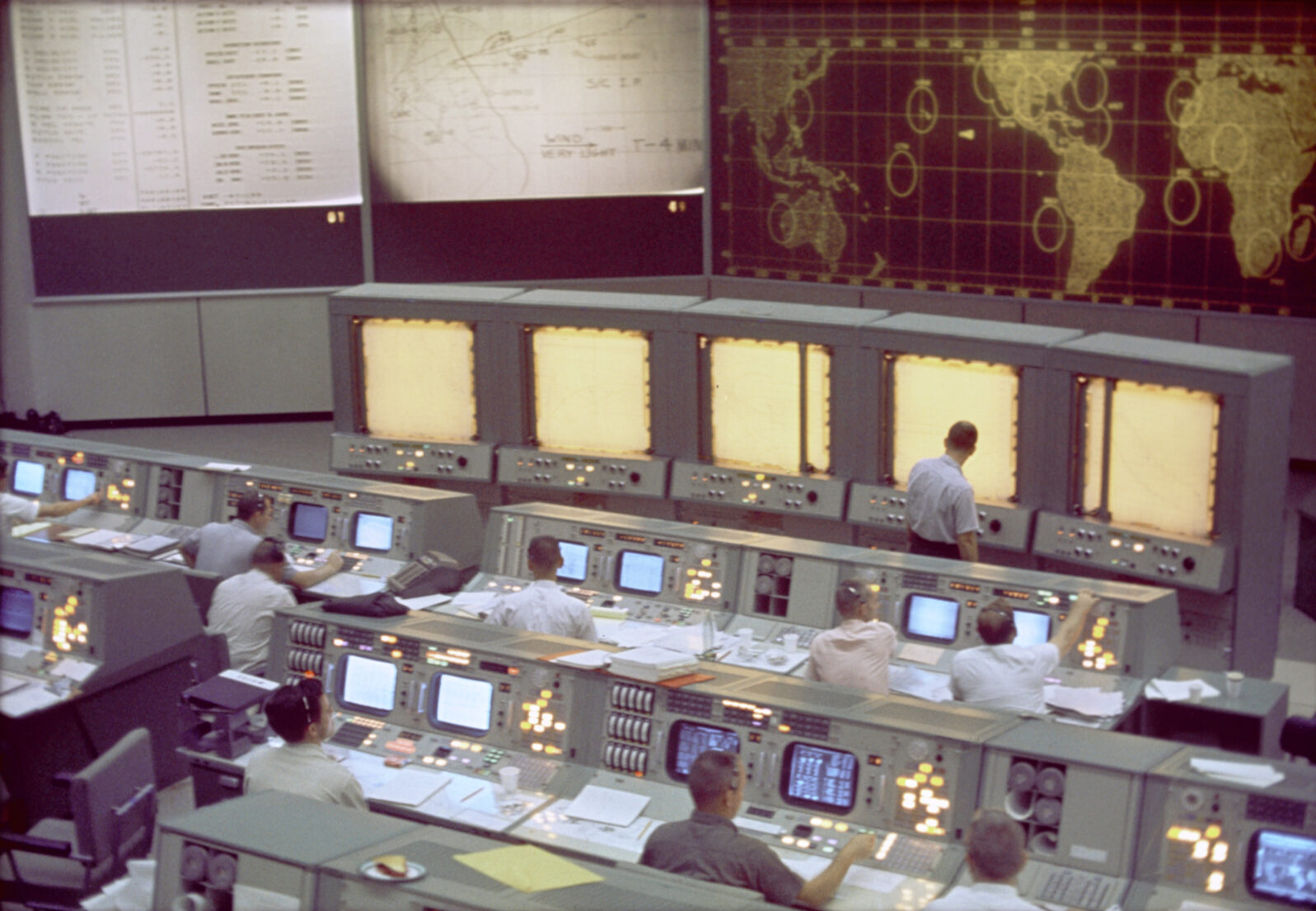

Reducing math and science to practice is what engineers do. Scientists didn’t put a man on the moon. Engineers did.(This essay begins an eight-part series on how to recruit and develop the workforce we need to continue the development of AI and advanced technology.)

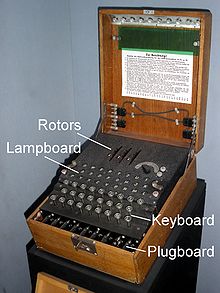

Who will continue the development and applications of AI in the future? How do we identify and recruit core contributors to computer technology? And how do we assess the larger problems of all of the technologies impacted by AI? The United States (or any country) needs a fresh stream of applied science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) professionals to develop and keep abreast of technical advancements. We need strong technical superiority, not only in high-tech business competition but in military strategy. WWII was shortened in Europe by radar technology and, as popularized in the movie The Imitation Game, by cracking the Nazi cipher code, Enigma. At the time, Alan Turing’s decrypting machine was at the very forefront of AI. Technology wins wars and STEM nerds innovate technology.

Engima, whose secret codes were deciphered by Alan Turing and others

Nearly all occupations surviving today’s AI tsunami will need computer literacy. When I was a boy, backyard mechanics could fix their trucks with a screwdriver and a crescent wrench. To service today’s cars, professional mechanics need to know how to use computers. Many occupations are and will continue to be enhanced by computer technology. Blue-collar Uber drivers must use GPS. The senior executives in the C-Suites of industry increasingly rely on data analytics and AI-based forecasting to run their companies. Overall, computer applications will impact our society and culture as much as electricity did. And we’re living smack in the middle of the transformation. Although we continue to be numbed by familiarity with the bright lights of future development, the beginning of the transformation is already here. GPS, Google maps, touch screens, social media, online shopping, ebooks, texting, streaming video, and search engines are all fruits of recent advanced technology we now not only enjoy but take for granted.

Maintaining the infrastructure and innovations of high tech is the job of STEM nerds. Many people only know about these STEM professions from NASA press releases and NOVA specials. But the topics the media cover are often not the most interesting, widespread, or lucrative of the STEM disciplines. For example, I teach electrical and computer engineering. When I started dating my (now) wife Monika, she confessed to being totally unaware of the fascinating things engineers do. That’s no surprise; there is lots of misunderstanding out there. I’ve been asked by acquaintances more than once questions like “Can you help me wire my house?” and “Can you help install more RAM in my computer?” because they think that an engineer is an all-purpose service technician. As it happens, I am an electrical and computer engineer, not an electrician or a computer technician. The fascinating story behind the contributions made by STEM professionals to the welfare and betterment of mankind is a little-known history.

We need creative STEM nerds in our future. They excite the economy and win wars. But debate rages about whether there is currently a true shortage of nerds. Like our carbon footprint and global warming, the STEM debate has become political. On the one hand, new STEM initiatives from our governments are everywhere. The federal government spends money on bureaucracies like the Committee on STEM Education drawn from 13 federal government agencies—a sort of bureaucracy of bureaucracies. Their purpose sounds like bureaucratic babble “facilitating a cohesive national [STEM] strategy, with new and repurposed funds, to increase the impact of federal investments…”1 Some federal programs like NASA, the NSF, the Department of Education and some states, including California and Florida, have also initiated programs of their own, with the goal of educating more STEM professionals. Are these and similar programs aimed at solving a crisis that doesn’t exist? Proponents of the many STEM programs often defend them by pointing to low STEM-related test scores in the United States. The problem, in my view, is not that American kids are stupid but that the education system itself is flawed. Troweling on another layer of bureaucracy and money is not going to help.

On the other hand, some knowledgeable sources claim that there is no projected shortfall in STEM professionals for the American economy. My professional society, the IEEE (Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers), is the world’s largest professional society with over 400,000 members. In 2013, the IEEE’s flagship publication, the IEEE Spectrum, denied a need for federal and state programs in a bluntly titled editorial, “The STEM Crisis is a Myth.”2 IEEE claims that only a fourth of STEM college graduates end up working in STEM fields anyway.

I suspect that this figure reflects a great deal of variation depending on the STEM specialties chosen. True, there is not a lot of demand for new graduates with degrees in astrophysics or differential topology. But the picture changes radically when we survey applied mathematics and science fields, where graduates are in considerable demand.

Reducing math and science to practice is what engineers do. Scientists didn’t put a man on the moon. Engineers did. The latest life-saving medical gizmo is also probably the work of an engineer, not a physician. The greater the demand for the specialty, the higher the salary for practitioners. That’s why engineering and computer science graduates attract higher salaries than other STEM majors.

Independent of whether or not there is a STEM crisis, there is an effective procedure for identification, motivation, and maturation of STEM students along the path to the STEM professions. In this series of essays, we’ll show how it works.

———————-

1 Science, Technology, Engineering and Math: Education for Global Leadership, U.S. Department of Education

2 Robert N. Charette, “The STEM Crisis Is a Myth,” IEEE Spectrum, August 30, 2013.

Next: 2. Not Everyone Is Lucky Enough To Be a Nerd

Robert J. Marks is the Director of the Walter Bradley Center for Natural and Artificial Intelligence and holds the position of Distinguished Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering at Baylor University.