Children are watching much less TV

But what we learned from children’s TV is coming back to haunt us Today, parents struggle with children spending too much time on interactive media. Indeed, interactive media have largely displaced TV for kids:

Today, parents struggle with children spending too much time on interactive media. Indeed, interactive media have largely displaced TV for kids:

Bernstein Research says “average audiences on kids’ networks are literally half of what they were six years ago” — about 1.25 million average viewers, down from roughly 2.5 million in 2011, in Nielsen C3 ratings for 2-11 viewers on a total day basis. Wayne Friedman, “Kids’ TV Viewing Records Big Declines” at MediaPost (September 15, 2017)

We were even told in 2015:

Mobile devices are so popular with kids that nearly half of the 800 parents quizzed by Miner & Co. reported that they confiscate their kids’ tablets when they act up and make them watch TV instead, thereby fostering a sort of Pavlovian response that equates TV with punishment. (That these parents simply don’t restrict their kids’ access to video altogether when they misbehave suggests that they’re raising a generation of spoiled content junkies, but that’s another story.) Anthony Crupi, “Televisions Are No Longer the Screen of Choice for Kids” at Ad Age

But many of the conflicts and controversies today are inherited from the golden age of children’s TV in the latter half of the last century. It’s time for a bit of retro:

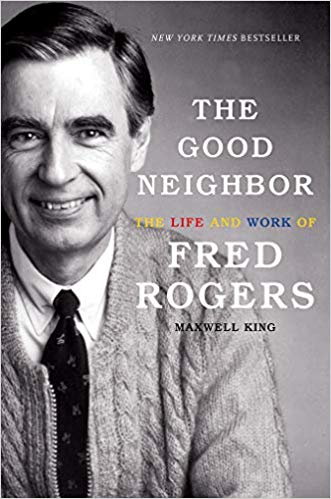

In the days when children’s television programming was as high tech as it got, Fred Rogers (1928–2003) of the iconic Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood (1968–2001) took the calm approach to spending time with children, the opposite of rival studio Sesame Street, according to journalist and essayist Maxwell King:

In a speech given at an academic conference at Yale University in 1972, Fred Rogers said, “The impact of television must be considered in the light of the possibility that children are exposed to experiences which may be far beyond what their egos can deal with effectively. Those of us who produce television must assume the responsibility for providing images of trustworthy available adults who will modulate these experiences and attempt to keep them within manageable limits.” Maxwell King, “Mr. Rogers vs. the Superheroes” at Longreads

He and child psychologist Margaret McFarland (1905–1988) tackled tough issues for kids in the Eighties— divorce, discipline, mistakes, anger, competition, and parents absent at work all week. But their aim was to “slow the world down and reduce some of the most confusing and troubling apprehensions of children to calm, thoughtful, and simple explication.” Rogers’s crew intentionally lengthened scenes as a theme week progressed and child attention spans expanded in response to a by-now familiar storyline:

Maxwell King

Academics who’ve studied Rogers’s work often marvel at how young children calm down, pay attention, and learn so much from this television production — and at how they remain calm and centered for some time after watching the Neighbourhood. … Many of the academics who studied early learning became advocates for the Neighborhood’s thoughtful, gentle approach.

But the Sesame Street approach came to dominate children’s programming. As King says,

The debate was not just about education and pacing. It was about childhood itself. … Sesame Street came to be viewed — sometimes to an unfair extent — as an example of a frenetic, intense, information-age approach that put cognitive learning first, cranked up the pressure, and foreshortened childhood in favor of learning letters and numbers. The pacing was set to be as fast as the times, with some emulation of Rowan & Martin’s Laugh-In and the television serial Batman.

Rogers did not like what he was seeing:

Early in the evolution of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, Rogers offered this definitive observation to a meeting of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry: “It’s easy to convince people that children need to learn the alphabet and numbers. . . . How do we help people to realize that what matters even more than the superimposition of adult symbols is how a person’s inner life finally puts together the alphabet and numbers of his outer life? What really matters is whether he uses the alphabet for the declaration of war or the description of a sunrise — his numbers for the final count at Buchenwald or the specifics of a brand-new bridge.”

Rogers, however, refused to be drawn by third parties into a conflict. Relations between the two groups were collegial, with Sesame Street’s Joan Ganz Cooney (1929– ) saying, ‘We are two sides of the same coin.’ . . . We were great admirers of each other. You know, Fred was unique. There had never been a Fred Rogers, and there wasn’t going to be another Fred Rogers.”

Possibly not. Looking around us, it seems obvious who won. And computer engineer Eric Holloway thinks that’s a problem:

One’s view of AI also influences education. If humans are just meat computers, then education is a matter of cramming enough “rules” in their head to make them operate effectively as part of the national machine.

On the other hand, if humans have immortal souls that can reason about abstract concept and have free will, then education should also give them time and space to learn to reason and exercise their free will.

Children really do need quiet, reflective time. It’s a copout on the part of adults to say, “Endless electronic noise is just the culture today and what can you do?”

Here’s what we can do: Adults don’t abandon a child to the passing traffic of the culture. But as they say during airplane safety demos: First secure your own mask before helping a child. Many of us might need to dial down the digital racket in our own lives before we can model human personhood for children.

Note: The essay at Longreads is an excerpt from The Good Neighbor: The Life and Work of Fred Rogers by longtime Pittsburgh journalist Maxwell King, about the life of classic children’s entertainer Fred Rogers (1928–2003). Hat tip: Eric Holloway

See also: Will AI triumph? Will that phone end up smarter than your kid? If so, it might not happen in quite the way we are told to fear. U.S. kids who spend more than two hours a day looking at screens “perform worse on memory, language and thinking tests than kids who spend less time in front of a device.”

and

Maybe iGen really is fragile. Did social media’s troll frenzies trigger the campus war on ideas?