Why Much Current Consciousness Research Is a Fool’s Errand

The inability to even define consciousness with clarity is emblematic of the conceptual mess that modern neuroscience has becomeRene Descartes 1596–1650) was a 17th century French philosopher, mathematician and natural scientist who was enormously influential in many disciplines, including philosophy of mind. For example, he broke away from the traditional understanding of the soul as the form or nature of the body, developed by Aristotle (384–322 BC) and refined by Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274).

In Descartes’ philosophy, the soul is, by contrast, a separate substance joined to the body. Thus the body is seen as a kind of biological machine run by the soul. The soul is, in the apt description of philosopher Gilbert Ryle (1900–1976), the “ghost in the machine.” His view, known as Cartesian dualism—which owes much to Plato—is a viable theory of the mind-body relationship but I think it is rather misguided.

The abandonment of the approach taken by Aristotle and Thomas (hylemorphic dualism) in favor of Descarte’s view has had unfortunate consequences for psychology and for theory of mind. One of them is that when modern thinkers abandoned the Cartesian “soul” substance—the ghost in the machine—they were left with the body as a mere biological machine. The new mechanical philosophy has made a mess of understanding the relationship between the mind and the brain ever since.

The mind–body connection problem

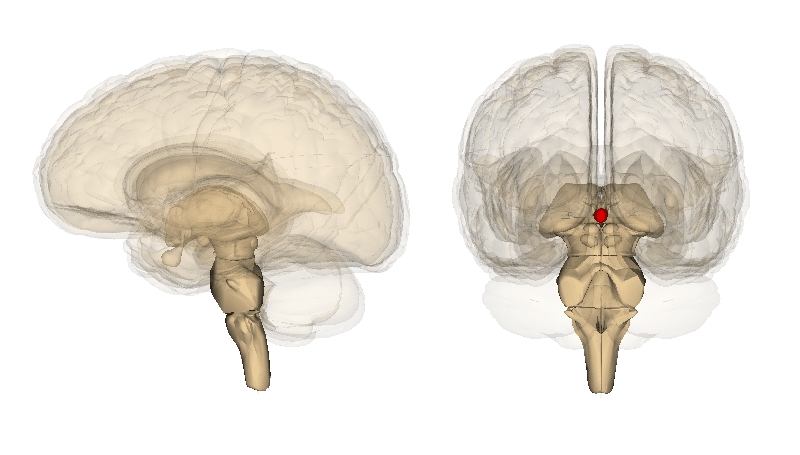

The Cartesian understanding of the soul as a separate substance from the body requires the two to “connect” somehow (the interaction problem). Thus Descartes was stuck with explaining how and where the soul plugged into the brain. He chose the pineal gland as the socket.

The pineal gland is a tiny one, deep in the middle of the brain. Descartes’ view that it was the connection between the immaterial soul and the material body seemed plausible by 17th century standards. Most parts of the brain are paired on the left and right, but the pineal gland is unpaired and sits in the middle.

Today, we know that the pineal gland has nothing to do with consciousness. Its function is rather obscure—it mediates day-night cycles of sleep to some extent—but you can live without one and be quite conscious.

While we now know that the pineal gland is not the socket for a “consciousness plug,” modern neuroscientists still search the brain for the center of consciousness, It is no longer understood as a socket because these neuroscientists are mostly materialists and thus reject the very existence of the soul. Rather, they seek a sort of consciousness CPU, as if the brain were a meat computer. I call that the Cartesian folly.

The underlying problem that underlies the Cartesian folly

Image Credit: Jorm Sangsorn -

Image Credit: Jorm Sangsorn - The fundamental problem with the present-day neuroscience of consciousness is that neuroscientists struggle even to define the term. Consciousness is not synonymous with arousal—you can be conscious of dreams while asleep and thus very un-aroused. At least 40% of people in the deepest level of un-arousal (persistent vegetative state) are conscious, as shown by careful testing. This inability to even define consciousness with clarity is emblematic of the conceptual mess that modern neuroscience has become. Entire disciplines of scientists are feverishly studying the physiology of something they can’t even define.

One result is that neuroscientists often confuse consciousness with arousal. Human consciousness is first-person subjective experience, the general experience of being an “I”. Arousal refers to awareness of the environment. There are most certainly brain regions that mediate arousal, the most important of which is the reticular activating system (RAS) in the brainstem. Injury to the RAS causes deep coma, but coma is not the same thing as unconsciousness, as we will see.

Why we can’t find consciousness in the brain

I define consciousness in a simple way: it is the means by which we have experience. By “experience” I mean the spectrum of the mental powers we use—moving, perceiving, remembering, emoting, imagining, understanding, judging, willing, etc. By “means” I mean that consciousness is the instrument that enables experience. But it is not something that can be known in itself.

Consciousness is somewhat like seeing through contact lenses. Nearsighted people can see clearly through them, but we don’t see the lenses themselves. In the same way, consciousness is a power of our soul that is always invisible to us, because it is the instrument, not the object, of our knowledge. It is the means by which we experience, not what we experience. Thus we can’t “find” it in the brain.

As theories rise and fall, a call for conceptual clarity,

Consciousness is not a spot, a lobe, or even a process in the brain. Yet the search for such things continues in the neuroscience community around the world.

Recently, as Denyse O’Leary, co-author with me of The Immortal Mind: a Neurosurgeon’s Case for the Existence of the Soul (June 3, 2025), points out here, the widely accepted recent theory that consciousness resides in the pre-frontal cortex (a modern iteration of Descartes’ theories about the pineal gland) has unexpectedly come under serious challenge.

Scientists at the Allen Brain Institute reported on a multi-year study testing Integrated Information Theory (IIT) against Global Workspace Theory (GWT), the two leading materialistic theories of consciousness. IIT and GWT are materialist theories of the mind that each posit a different kind of brain socket (or CPU or whatever) for consciousness, although both theories posit that the prefrontal cortex as the region of the brain is essential to consciousness.

Their study shows that the pre-frontal cortex is much less important to consciousness than previously thought and that measurement of brain activity in the prefrontal cortex supports neither theory. I would like to point out that these neuroscientists could have saved themselves a lot of time and money (their time and our money) simply by meeting a person with hydranencephaly, a congenital brain disorder in which people are born without brain hemispheres and without a cerebral cortex, pre-frontal or otherwise. People with hydranencephaly are severely disabled, but they are fully conscious, and have a broad range of mental states such as joy, sadness, fear, longing, etc.

You don’t need a prefrontal cortex, or any cortex at all, or even brain hemispheres, to be conscious. You need brain parts to do some mental things—to see, to move, to feel, to remember, etc., but consciousness is not made of meat. You need a soul—in the case of human beings, a spiritual soul— to be conscious. Yet materialists keep searching for the mechanism of consciousness as if it were a gadget in a meat machine.

Consciousness is the ability conferred by our spiritual soul to have experience—the means, not the object, of our thoughts. While the brain plays important roles in our perception, movement, emotions, memories, etc., the search for consciousness in the pineal gland or the prefrontal cortex or anywhere in the brain is, and will always be, a fool’s errand.

Note: You can preorder The Immortal Mind: A Neurosurgeon’s Case for the Existence of the Soul by Michael Egnor and Denyse O’Leary (Hachette Worthy, June 3, 2025). Here’s what people are saying about the book.