Is Panpsychism Putting Francis Crick’s Pack of Neurons to Flight?

Science writer John Horgan remembers Crick in the ‘90s when reductionism was riding high in neuroscience. What’s happened since?

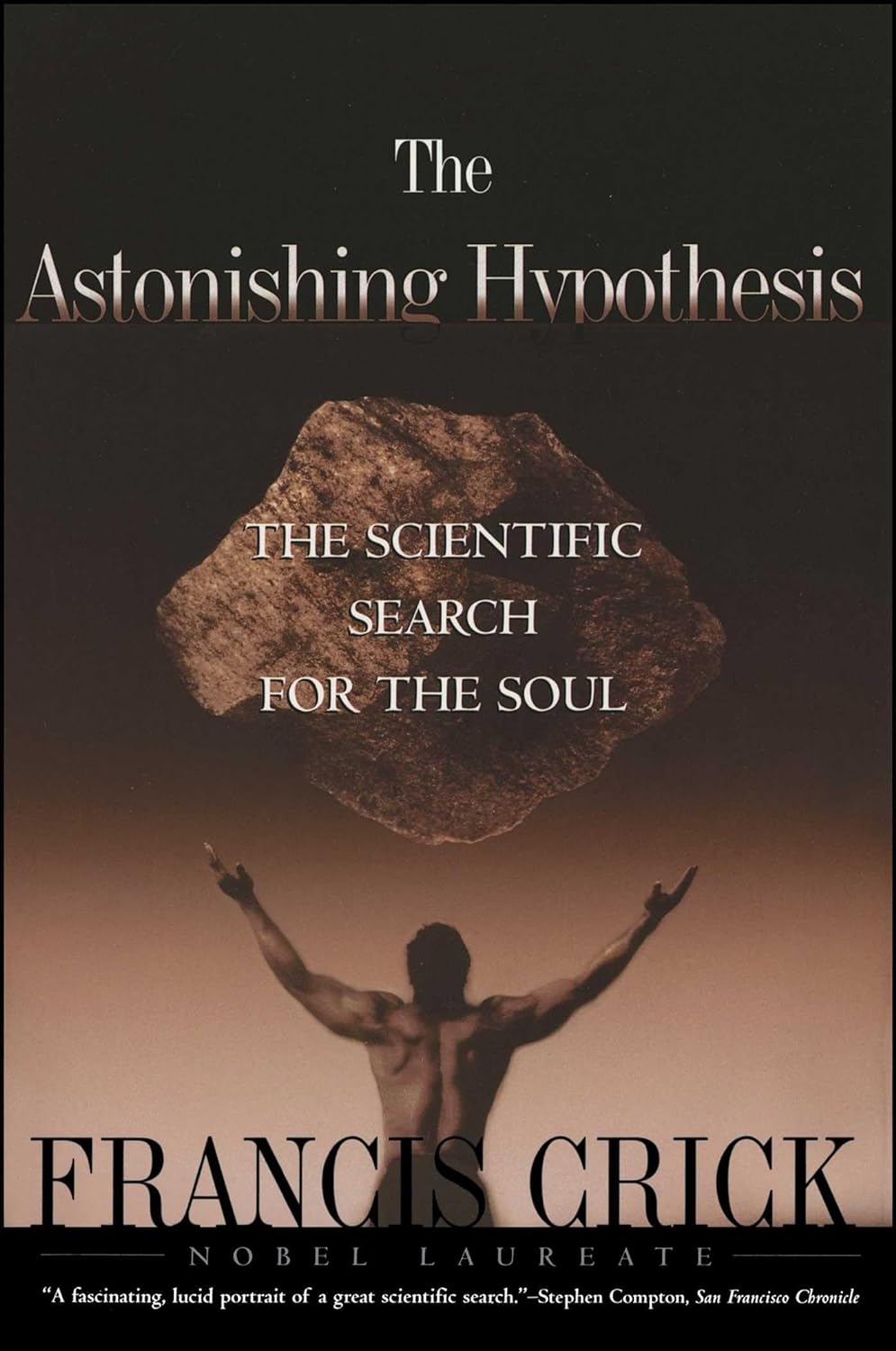

On Monday, science writer John Horgan recalled a 1991 conversation with genome mapper Francis Crick (1916–2004), who, later in his career, became interested in consciousness. Crick was a “ruthless reductionist” who was working at the time on a book, The Astonishing Hypothesis (Scribner 1994), which advises the reader that “You’re nothing but a pack of neurons.”

From reductionism to panpsychism

At the time, Crick was working with neuroscientist Christof Koch on a theory of attention (how we pay attention to something), hoping that a promising theory might help unravel the mystery of consciousness:

Crick and his collaborator Christof Koch have proposed a tentative answer to the puzzle of attention. Experiments suggest that when the visual cortex is responding to a stimulus, certain groups of neurons fire rapidly, 40 times per second, and in synchrony.

These 40-hertz oscillations, Crick and Koch propose, might correspond to the object of our attention. If one envisions all the neurons in a brain as a vast, chattering crowd, the oscillating neurons are a subset singing the same song.

John Horgan, “Francis Crick’s depressing hypothesis,” John Horgan (the Science Writer), July 8, 2024

Unfortunately, their best results came from anesthetized cats and Crick was doubtful that the theory would be fruitful. In 2003, he and Koch decided that the hypothesis was not really a strong one. Crick died not long afterwards.

And Koch? Well, Horgan reminds us, he went on to champion Integrated Information Theory (IIT) which, as he puts it, “implies that consciousness is a property not just of brains but of all matter.” In short, panpsychism.

An even more astonishing hypothesis

It’s not too much to say that, for most materialist neuroscientists, anything remotely resembling panpsychism (everything is conscious) is a much more astonishing hypothesis than anything Crick, a classic 20th-century materialist, could have come up with.

It all came to a head last September when Koch was charged with “pseudoscience” in a Cancel letter signed by a number of influential figures in the discipline. The ensuing uproar risked devolving the entire field of consciousness studies — which had always struggled to be taken seriously — into a loud and expensive catfight.

It’s ironic, as Horgan points out, that Crick was the figure whose interest in consciousness had lent credibility to the discipline in the 1990s by declaring it a “legitimate scientific problem.” And now, those who had inherited the hard-won credibility appeared to be throwing it away in a full frontal assault on his colleague.

The underlying fault in the field of consciousness studies

Crick likely lent credibility to the discipline insofar as the goal — the only permissible goal — was a reductionist “pack of neurons” account of consciousness. Seen from that perspective, the purpose of the discipline of consciousness studies is to find an entirely material account of an obviously immaterial phenomenon.

A panpsychist account is usually materialist too, of course. But if consciousness pervades all life forms or all of nature, as the panpsychist proposes, it can’t be reduced to an effect created by a pack of neurons. There must be more to it than that.

Panpsychism would let neuroscientists keep overall materialism but at the price of giving up Crick’s reductionism. And they risked the credibility of the entire discipline in the act of loudly saying no.

As the years wear on, consciousness will likely remain irreducible and panpsychism will prove harder to deal with merely by attempts at deplatforming. The neuroscientists may end up having to address plausible claims for dualism soon too.

You may also wish to read: The philosopher wins: There’s no “consciousness spot” in the brain. After a 25-year search, dualist philosopher David Chalmers won the bet with neuroscientist Christof Koch, whose consciousness theory has panpsychist overtones. As dualist neurosurgeon Michael Egnor notes, human consciousness is immaterial by nature. Is the Koch-Chalmers bet a language game aimed at avoiding that fact?