Neuroscientist: Human Brain More Complex Than the Models Show

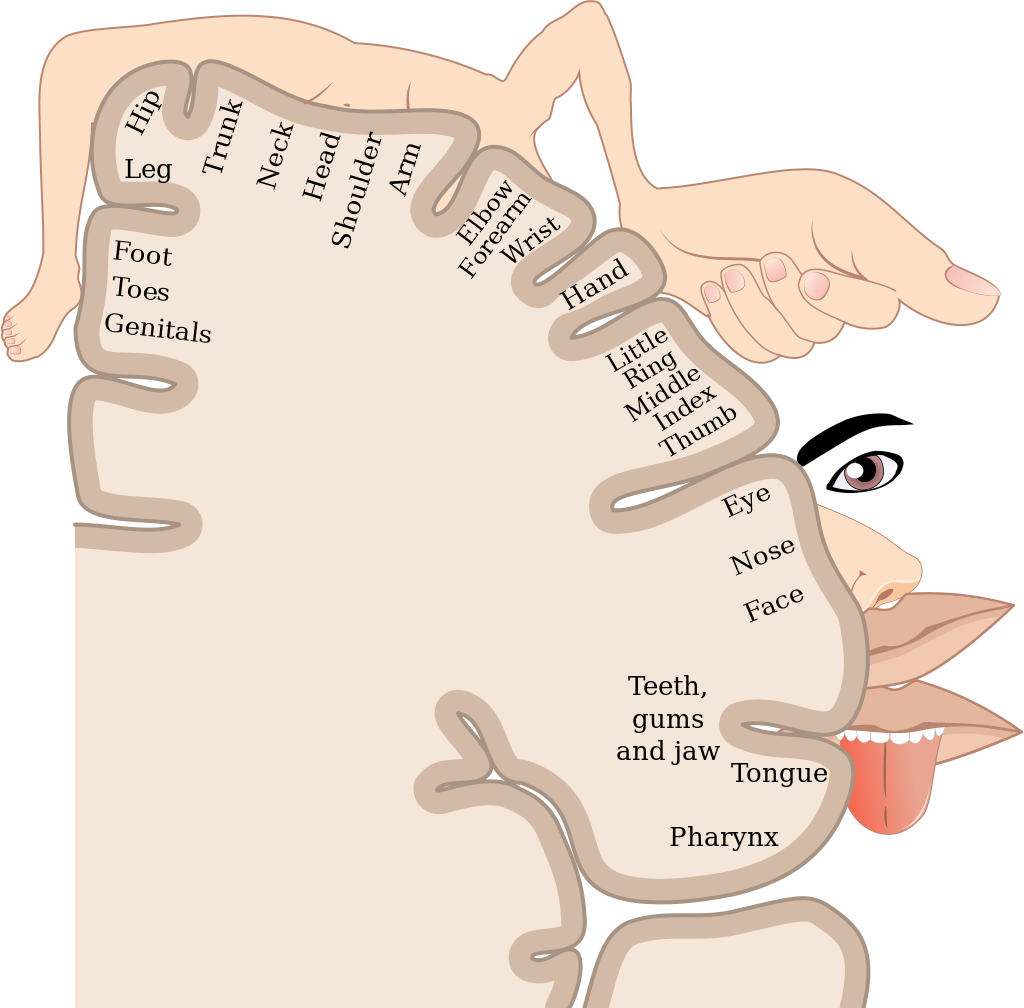

The weird “homunculus” — the way the brain maps the body — was pioneer neurosurgeons’ best guess nearly a century agoStudents in neuroscience must meet the homunculus, the brain’s weirdly distorted map of the body. The map comes in two views, motor and sensory.

In either case, it’s distorted because the human brain pays much more attention, for example, to sensations around the lips than sensations around the underside of the upper arm. Thus, you can feel your lips quite easily. But you might have to concentrate a bit to feel any specific portion of the underside of your upper arm, unless it is hurting.

from Anatomy & Physiology, Connexions/

CC BY 3.0

and Rasmussen (1950)/CC BY 3.0

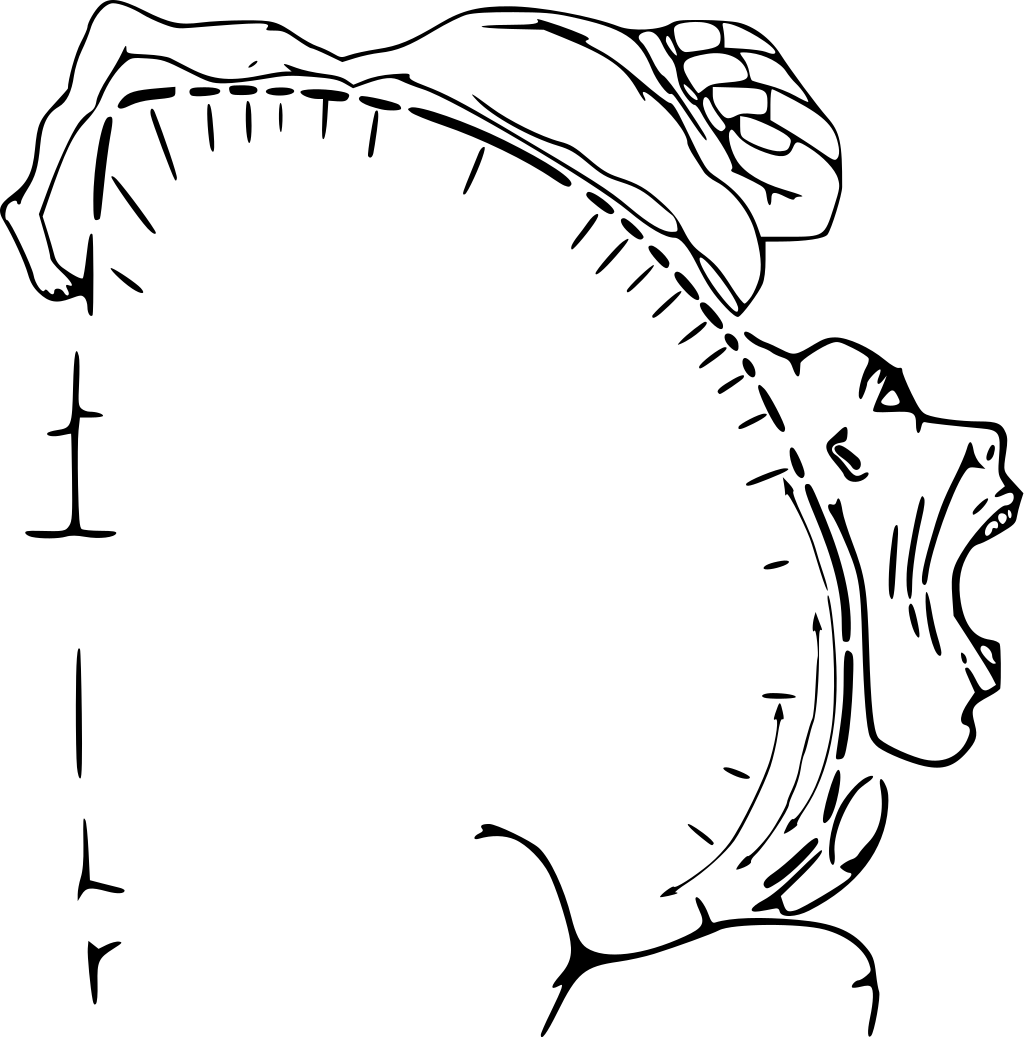

The homunculus originated with 20th-century Canadian neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield (1891–1976) and his colleagues. Pioneering neurosurgery techniques to treat epilepsy that did not respond to drugs, they had to keep patients awake during the procedure in order to know what parts of the brain could be safely removed. They learned a good deal that way about the relationship between parts of the brain and parts of the body, which they depicted as the homunculus.

Penfield placed stickers on the exposed patient’s brain to identify by number the area that stimulation had aroused.

Neurobiologist Moheb Costandiis explains at Aeon that the brain’s map is created by “two narrow, adjacent strips of tissue that run down from the top to the bottom of the brain on either side of the central sulcus, a deep fissure separating the frontal and parietal lobes.”

But now, according to Costandiis, author of Body Am I (Penguin Random House 2024), our view of the homunculus might be a bit out of date. The brain is more complex than 20th century surgeons and researchers realized. Later researchers, analyzing 50,000 brain scans,

… found that movement of the feet, hands and face was associated with the parts of the motor cortex identified by Penfield, but that interspersed between these discrete regions were other areas that did not seem to be involved in movement at all. These other regions were thinner than the flanking regions associated with individual parts of the body, and were connected to each other, both within the same and between the two hemispheres of the brain, to form a chain running down the motor strip.

Further investigation revealed that these areas are also strongly connected to distant brain regions involved in ‘executive’ functions such as thinking and planning, visual processing and the processing of touch, pain and internal bodily signals, and that they became active when the participants thought about moving.

Moheb Costandiis, “Rethinking the homunculus,” Aeon, March 1, 2024

Thus, they found that the homunculus is “wrong or at least spectacularly incomplete.”

The female brain is not well represented by the homunulus

Another way the homunculus is incomplete is that it lacks a clear representation of the female brain:

It’s also worth discussing what’s been called the ‘hermonculus’. The homunculus is a composite of localisation data that Penfield obtained from the presurgical evaluation of some 400 patients. Yet, while the homunculus clearly shows the cortical representation of male genitalia, female anatomical parts are conspicuously absent. The reasons for this are unclear. It may be because Penfield worked at a time when it was considered inappropriate to ask about or report certain sensations experienced by his female patients; because female patients felt embarrassed reporting genital sensations to male authority figures; or because Hortense Cantlie, the medical illustrator who drew the homunculus, may have been uncomfortable incorporating female genitalia into her illustrations.

Costandiis, “Rethinking the homunculus,”

Of course, as Costandiis points out, lack of data may also be due to the less lively fact that only nine women were part of the homunculus study group. More recent studies, as he says, have produced conflicting results so the pursuit of the “hermunculus” continues.

No one should be surprised if the brain turns out to be more complex than was earlier expected. Most modern research into human beings, honestly considered, is turning out that way.

You may also wish to read: Why pioneer neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield said the mind is more than the brain. He gave three lines of reasoning, based on brain surgery on over a thousand patients. Michael Egnor points out that Penfield offered three lines of evidence: His inability to stimulate intellectual thought during brain operations, the inability of seizures to cause intellectual thought, and his inability to stimulate the will. … So he concluded that the intellect and the will are not from the brain. Which is precisely what Aristotle said.